Alaska Fisheries Sonar

Sonar Tools: Split-Beam

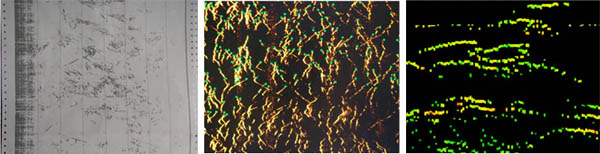

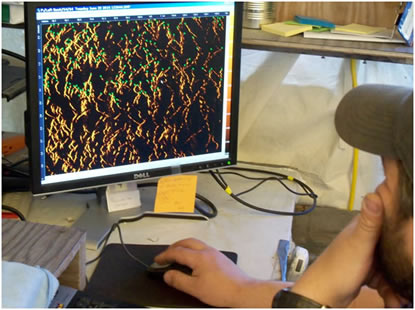

Split-Beam Sonar

In the 1990s the Alaska Department of Fish and Game expanded its sonar tool kit with the introduction of split-beam sonar. Split-beam sonar is technically complex to operate, but biologists can use it to collect information about a fish’s three-dimensional position and travel direction to distinguish upstream-migrating fish from downstream-moving fish and debris. Biologists can use split-beam sonar to detect fish swimming far from shore.

When split-beam sonar is the right tool for the job

Today biologists can more easily and accurately collect information about fish position, travel direction and size using DIDSON technology. But split-beam sonar is still the best tool available for detecting fish at long ranges. While biologists can use DIDSON technology to detect fish out to about 150 feet from the transducer, they can use split-beam sonar to detect fish out to about 1,000 feet from the transducer. Two ADF&G sonar projects require long-range detection of fish and use split-beam sonar — the Pilot Station sonar site and Eagle sonar site, both located on the Yukon River.

Getting into the water

To deploy a split-beam sonar transducer, sonar site technicians mount the transducer to a tripod and submerge it near shore. They then aim the transducer sonar beam offshore and perpendicular to the river’s current along a section of the river bottom with a smooth, uniform slope. They must aim the transducer beam close enough to the river bottom so that fish cannot swim below it undetected, but high enough so that contact with river bottom does not disrupt detection of fish echoes with acoustical noise.