Alaska Fisheries Sonar

Sonar Technology Tools

Alaska Department of Fish and Game sonar tools

Alaska has been a pioneer in the use of sonar to detect fish in rivers. In the more than 40 years that ADF&G has used sonar in rivers, its tools and methods have progressed to provide increasingly more detailed information about sonar-detected fish.

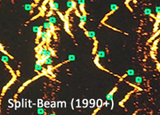

Since the program began, ADF&G has used three types of sonar technology—Bendix sonar, split-beam sonar and imaging sonar (DIDSON and ARIS). Today we rely almost entirely on imaging sonar, as all Bendix sonars have been replaced with imaging sonar units. Out of 15 ADF&G sonar sites, 12 sites use imaging sonar exclusively, while two sites use a combination of split-beam and imaging sonar.

| Bendix Sonar | Split-Beam | Imaging Sonar | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Detection method | Counts echoes | Produces fish traces | Produces high-resolution fish video | |||

| Max distance of fish detection | ~30 meters (approx. 100 feet) | ~300 meters (approx. 985 feet) | ~40 meters (approx. 130 feet) | |||

| Determines fish travel direction | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Can be used to calculate fish length | No | No | Yes | |||

| Identifies Fish Species | No | No | No | |||

How sonar technology works

The basics of how sonar finds fish in a river are simple. First, a sonar transducer submerged in the river emits a beam of sound waves into the water. When the sound waves encounter an object with a density different than water, such as a fish's swim bladder, some of the sound waves bounce back to the transducer as echoes. The transducer detects these echoes and fisheries biologists then analyze transducer data to provide information about fish in the river.

- Sonar 101 in the Upper Cook Inlet Region (PDF 318 kB)

- Sonar Basics in the Arctic Yukon-Kuskokwim Region (PDF 2,094 kB)