Living with Wildlife in Anchorage:

A Cooperative Planning Effort

Chapter 6: Priority Actions (Part 3)

Wildlife Recreation and Education Actions

These seven actions address the need to increase opportunities for residents and visitors to learn about wildlife and participate in wildlife-oriented recreation. These actions are designed to improve facilities, promote wildlife opportunities, and increase staff in interpretive and education programs. If these actions can be accomplished (and some are admittedly longer-term projects), Anchorage will have one of the best wildlife recreation education and learning opportunities of any large urban area in the country.

These actions recognize that residents and visitors are interested in a diversity of wildlife-related recreation and learning opportunities. Accordingly, these actions address the needs of the young and old, the active and less active, and those with an intense or more transitory interest in wildlife.

These actions begin with the development of an Anchorage Wildlife Festival to promote the variety of benefits that wildlife bring to the community, and a paired Anchorage Watchable Wildlife video and guide to suggest wildlife-recreation and learning opportunities in the city.

The next two actions address the need to more fully staff existing wildlife education programs in Anchorage's schools and visitor centers, while another two actions identify demand for two additional visitor centers, at Potter Marsh and Girdwood, which would complement the existing nature/interpretive facilities downtown (APLIC), in Eagle River, and in BLM's Campbell Tract. A final high priority packages a series of actions along the corridor from Potter Marsh to Girdwood, which has unparalleled diversity of wildlife viewing and learning opportunities.

Finally, this section identifies a series of supported (but lower priority) wildlife recreation facility actions in Chugach State Park, along city greenways, and on BLM land. Many of these proposals are in existing plans or have been previously proposed. This plan simply endorses those projects for their wildlife components.

17. Anchorage Wildlife Festival

Description. This action would provide for a variety of wildlife education opportunities, encourage wildlife volunteerism, and generally promote the benefits of Anchorage's wildlife. It might also include a wildlife count effort and could be integrated with a habitat awards program as described earlier. Moose, bear, lynx, loons, geese and songbirds are among the many animals that could be highlighted. This event would be the first of its kind in Anchorage. It will provide an opportunity for residents to learn more about preserving and enjoying the diverse and unique wildlife of Alaska's largest city.

This action could include displays and educational materials from wildlife-related agencies, conservation organizations, businesses, tourism interests and others. An “Anchorage Wildlife Week” could be proclaimed, during which a one-day festival, daily workshops and wildlife awareness could all be promoted. This action could also serve as the foundation for promoting the Municipality as a premiere wildlife viewing destination for tourists coming to Alaska.

This action might also be coordinated with existing wildlife-related public events, including the International Migratory Bird Day (which is typically celebrated with festivities in Kincaid Park in mid-May), the Alaska Loon Festival (also held in May), the Alaska Bear Festival, or the U S Fish and Wildlife Service Open House (held every three years in the fall, drawing over 1,000 people).

Rationale. This action would provide the public forum for advocating several goals and actions of the Anchorage Wildlife Plan. For example, guidelines and agency experts would be available to answer specific questions from participants on human-wildlife conflicts. A GIS map of wildlife habitat in and around the city would be on display for residents and developers alike. A wildlife count would aid in population assessment and monitoring. An Anchorage Wildlife Viewing Guide could be effectively distributed.

Responsibilities. The lead organization could be the Alaska Wildlife Alliance, a non-profit dedicated to protecting Alaska's wildlife. Wildlife conservation groups would be invited to co-sponsor the event, along with ADF&G, USFWS, BLM, the Municipality, and the military installations. The multi-agency Watchable Wildlife Committee, the Alaska Visitors Association, and other municipal/community leaders would also be encouraged to participate. Materials, events, and networking would be of interest and use to a wide range of adults, children, residents, tourists, businesses, and schools.

Schedule. An Anchorage Wildlife Festival could be scheduled as early as the spring, summer, or fall of 2000. A summer date may prove more beneficial in that tourists could attend, and allow for a large-scale outdoor event. The disadvantage to a summer date is that a wildlife festival would compete in a crowded summer events schedule. As an alternative, a spring or fall date could be coordinated with the existing wildlife events, but may be more focused on residential wildlife issues.

Costs and Funding Sources. The costs of a wildlife festival would depend on the size of the event. A recent festival for Alaska's bears cost $4,000 and was held in the Loussac Library with approximately 500 participants. Organization and input was mostly voluntary. The Anchorage Summer Solstice Festival sponsored by AWAIC draws thousands of people and costs $30,000 to produce. An urban wildlife festival could start small and be allowed to grow to a full-scale municipal, tourist, and possibly school event. Potential funding sources for this type of event are almost limitless. Immediate possibilities are wildlife conservation foundations. Corporate sponsors, local businesses, and national urban wildlife interests might also be explored as funding sources.

Constraints. The constraints for this action would depend upon the scale of the event. Organization, funding, and marketing are the greatest challenges. Of course, an outdoor event's success can also be weather-dependent.

18. Anchorage Watchable Wildlife Guide and Video

Description. Produce a twenty-minute narrated video tape and accompanying booklet/guide that would:

- Introduce the viewer to a number of popular wildlife viewing sites and scenic places within the Greater Anchorage Area.

- Provide guidance on how to behave around different wildlife from both an ethical and safety standpoint.

- Develop the theme that Anchorage is a special city with abundant wildlands and wildlife at its doorstep. Anchorage without its “wild” would lose the charisma and charm that makes it an exciting place to live and visit.

The video should emphasize that the conservation of wildlife and natural resources require attention and commitment from both residents and visitors.

Rationale. A tape and booklet would have many uses. They could be used in schools to create interest in wildlife, instill appropriate wildlife ethics and values, and provide safety information that could prevent potential conflicts. They could be used by hotels, local businesses and tourist enterprises as a service to the public. Scouts and other youth groups and organizations might also find them beneficial. They could be used at conventions and business meetings. The video could be made available to public TV and the outdoor channel so it could potentially reach a wider audience.

Responsibilities. The lead on this action is likely to be ADF&G, which should at least have a major technical role in providing factual information. Chugach State Park would also be an informational contributor, as the video is likely to focus on many opportunities in the park. However, there are many options regarding the writing of the script and actual production. For example, Colorado State University has produced several excellent videos and other public information materials for the military in Alaska regarding training and environmental/natural resource subjects. One of these productions received a “Telly Award” in 1998, a prestigious international award for documentary productions. They have excellent writers, production expertise and familiarity with Alaska and the Anchorage area. There is also the possibility of contracting with one of the several local video production companies.

Costs and Funding Sources. Production estimates for a high quality 20-minute video approach $45,000. The cost of duplicating tapes after the initial production costs should be in the neighborhood of $3 to $4 each. Cost for production of a brochure can vary widely ($3,000 to $10,000) depending on style, size, paper type, use of artwork or photos, maps etc. Costs of running copies after the initial design can vary between $1 and $3.50 each depending on level of detail and sophistication.

Potential sources of funding include federal CARA funds, the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, Dept. of Tourism, federal, state, and municipal agencies, and local businesses and organizations.

19. Expand Wildlife Education in Anchorage Schools

Description. This action would increase funding of wildlife education in Anchorage public schools. There are several existing programs (e.g., Project Wild, Alaska Wildlife Curriculum, Project Learning Tree, Anchorage Committee for Resource Education, Alaska Natural Resource and Outdoor Education Association) that provide teacher training and materials on wildlife education issues. In addition, programs at the Alaska Public Lands Information Center (APLIC) also provide age-appropriate information and facilities for up to 6,000 school children visits per year. However, these programs are generally short-staffed and are unable to meet recognized demand from schools and other groups who would like their help in implementing wildlife education efforts. This action would expand these programs in the Anchorage area (while recognizing that this is a problem state-wide as well).

Many states fund these programs at higher levels. In Colorado, for example, students in the sixth grade attend a six-week environmental education field camp. In Alaska, training is typically provided for less than 200 teachers per year, and staff have a very limited ability to participate in actual wildlife education opportunities with teachers. In general, the problem is a lack of staff, not the lack of materials.

This action would fund two additional positions to coordinate and staff existing programs. One position each would be located in ADF&G and USFWS. They would focus on teacher training and conducting some wildlife education classes themselves. They could also help coordinate curricula changes that focus on Anchorage wildlife.

Rationale. This action addresses the need for additional wildlife education in Anchorage, a major planning goal. Schools and other youth organizations have demonstrated high demand for more training and activities; this action would allow area agencies to fulfill that demand. This would not detract from other subjects because wildlife education can be a theme used to teach basic skill development in English, math, science, or other subjects.

Responsibilities. Lead agencies are ADF&G and USFWS, both of which operate wildlife education programs. Anchorage school district is a major cooperating agency, as it would be the chief beneficiary of specific work. Officials or staff from APLIC, ANHA, Campbell Creek Science Center, and other facilities with wildlife education responsibilities may also want to become involved. Cooperation with Anchorage School District is also important, although actual demand tends to be driven by teachers on an individual basis.

Schedule. This action could be implemented very quickly if funding were secured. Both ADF&G and USFWS have the ability and expertise to hire and supervise potential positions.

Costs and Funding Sources. Annual costs for a wildlife education position are about $50,000 per year, which includes salary, benefits, and support equipment. Total cost for two positions is thus $100,000 per year. Potential funding sources include CARA, or other appropriations through Congress or the state legislature. Anchorage wildlife education programs would be beneficial even if staff were assigned statewide responsibilities because roughly half the state lives in the Anchorage area.

Constraints. Funding sources may not be able to support staff positions. Agencies may be reluctant to hire positions on “soft” money developed through grants or one-time legislative appropriations.

20. Expand Wildlife Education/Interpretation Programs at Area Visitor Centers

Description. This action would increase funding for interpretive positions at the variety of Anchorage nature centers (including the Alaska Public Lands Information Center, Eagle River Visitor Center, Campbell Creek Science Center, and the proposed nature centers at Potter Marsh and Girdwood). The intent is to cooperatively fund these positions and rotate interpreters through the various visitor centers in the Anchorage area. This will increase cooperation and integration of interpretive efforts among the various centers, as well as help meet latent demand for interpretive activities.

Rationale. This action would also address the need for additional wildlife education in Anchorage, a major planning goal. In this action, however, the focus is on area interpretive visitor centers, particularly in the summer. There are several visitor centers that provide wildlife information to Anchorage residents and visitors, but some have chronic funding shortfalls. This action would provide funding for additional positions so that operating hours can be extended, and more activities and programs produced.

Responsibilities. The three existing visitor centers have funding structures in place through Alaska State Parks, BLM, and the Congressionally-mandated but cooperatively funded APLIC.

Schedule. This action could be implemented immediately upon funding. As discussed above, demand for interpretive programs and longer visitor center hours is during the summer months, so positions could be seasonal.

Costs and Funding Sources. Interpreters cost about $3,000 per month and could be hired on a seasonal basis. As a starting point, we envision the need for approximately two positions to be rotated among visitors centers over a seven-month summer season (April – October). Possible funding sources could include CARA, or other state and federal legislative appropriations.

Constraints. Developing multi-agency cooperative positions (so interpreters can rotate their efforts at several interpretive facilities in Anchorage), and establishing funding sources.

21. The Alaska Bird Center at Potter Marsh, and Potter Marsh Boardwalk Expansion

Description: The Bird Treatment and Learning Center (Bird TLC) is developing the Alaska Bird Center at Potter Marsh (Center), a joint-use educational facility and bird rehabilitation clinic. Bird TLC is a nonprofit group dedicated to treating injured wild birds and providing education about wild bird conservation, but it does not have a permanent, consolidated facility for these services. Bird TLC has purchased a 4.3 acre building site overlooking and adjacent to Potter Marsh, a state wildlife refuge.

The Center’s mission is the conservation of Alaska’s birds and their habitats through public education, and rehabilitation of injured and orphaned wild birds. Educational exhibits, programs and activities will be developed around the theme that Potter Marsh is part of a network of valuable wetlands and wildlife habitats and that its conservation depends on human actions. A market study in 1998 predicted the Center could attract 218,000 residents and visitors per year at a $12 admission price.

Potter Marsh is one of the most popular fish and wildlife viewing areas in Anchorage, featuring nesting bald eagles, spawning salmon and a variety of nesting and migratory water birds. Current facilities include a 1,550-foot boardwalk with interpretive signs accessible from a small parking lot off New Seward Highway. The ADF&G estimated nearly 45,000 visitors used the Potter Marsh boardwalk during the summer of 1997. ADF&G has obtained federal highway funds to design parking lot improvements and an extension of the boardwalk to link to the Center site.

Rationale. This project helps meet several wildlife education and recreation goals outlined in this plan, as well as treat injured birds. It most directly serves the goal of providing for wildlife education and recreation opportunities in an area with abundant summer wildlife.

Responsibilities: Bird TLC has developed a partnership with the ADF&G (which manages Potter Marsh), Alaska State Parks (which manages nearby Chugach State Park), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the non-profit Friends of Potter Marsh (FOPM) to develop the Center and cooperate on educational services. ADF&G is responsible for coordinating the boardwalk link to the marsh.

Estimated Schedule. Design and environmental review of the boardwalk and Center is on-going and will be complete when construction begins in 2001. The Center is expected to open in 2003-04.

Costs and Funding Sources. Phase II/Planning would cost $475,000; Phase III/Construction and Startup is estimated at $13 million. Both public and private funding is being solicited.

Constraints. The Center and boardwalk development are subject to local, state and federal government permitting, and obtaining adequate funding.

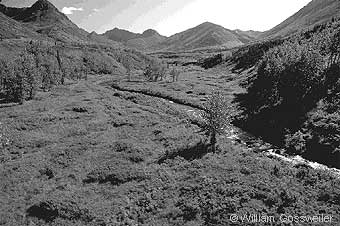

22. Wildlife Recreation Planning for Potter Marsh to Girdwood Corridor

Description. This action envisions a coordinated planning and development effort to improve and integrate a series of wildlife-oriented recreation opportunities along a corridor from Potter Marsh to Girdwood. The state Department of Transportation (DOT) is involved with significant highway reconstructions along this corridor, and a multiple-use trail is expected be built in conjunction with them. This action recommends beginning a planning effort to coordinate those projects and ensure they include several related wildlife recreation and learning opportunities. In addition, this type of planning could ensure that the provision of these opportunities minimizes adverse impacts on the wildlife and natural resources that draw people to the area.

Specific projects likely to be considered and recommended during this planning effort include:

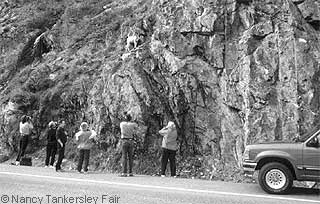

- Viewing improvements and interpretive stations at Beluga Point.

- Viewing improvements, parking, and interpretive stations at Windy Corner.

- A beaver pond overlook and interpretive trail at Bird Point.

- A tidal marsh overlook and interpretive station at Girdwood Marsh.

- The Alaska Bird Center at Potter Marsh (see Action 21).

The ultimate vision is of a series of connected recreation and learning opportunities, along with nodal infrastructure (on private lands) so that visitors may be able to step out of Anchorage hotels and connect with trails that will take them 40 miles to Girdwood. The combination of scenery and wildlife viewing (along with some history) is compelling. With planning, we have the chance to conserve and enhance these opportunities.

Rationale. The area between Potter Marsh and Girdwood captures some of Alaska’s most spectacular views. It provides a landscape that intersects land and sea, mudflats and tundra, and caters to colorful horizons. With the exception of Dall sheep at Windy Corner, beluga whales, and free-ranging bald eagles, wildlife currently plays only a supporting role.

Visitors and Alaskan residents more often travel the corridor to get somewhere – a string of places and activities that symbolize Alaska during its frenetic warmer months. In fall and winter months, even fewer travelers focus on the road, with its brooding, majestic, powerful, dangerous, and reflective landscapes. Both automobile and train travelers are removed from this environment and its wildlife inhabitants, steered by internal clocks and insulated by glass – they don’t step far afield.

Wildlife recreation planning could help shape an alternative. It is by definition more invasive and yet can also allow greater subtlety. Unless carefully planned, the incremental loading of bicycles and recreational hikers will wear out its welcome. The issues are challenging: when to encourage interface and when to build imaginary fences to prevent unacceptable impacts; how to support access, but discourage exploitation. In order to meet this challenge, a public planning effort based on “limits of acceptable change” and other visitor impact planning frameworks is crucial.

Responsibilities. Alaska State Parks is the lead agency for these projects, but will need assistance from other governmental agencies and local conservation and trail advocates. The Department of Transportation is also a critical player, as it oversees the major road reconstruction that opens the door for many of these other possibilities.

Schedule. Some of these site projects and the longer multiple use trail are already being planned and developed. This action envisions additional planning to coordinate these projects and develop an overall vision for wildlife-related recreation in the corridor. This action could begin upon completion of this plan, if funding can be found. A one-year planning effort is envisioned. Some of the projects being proposed will likely be developed in the next two or three years; others are longer term efforts and would involve substantial government and private sector interest.

Costs and funding sources. An overall planning effort of this nature would require at least one full-time planner to organize over a one-year period at about $50,000. Additional agency participation might also cost significant amounts. CARA and Land and Water funding are possibilities for specific projects, as is ISTEA funding associated with road reconstruction. Planning money is less easy to secure.

Constraints. Finding funding for additional planning is a chronic problem, particularly when some of the projects under consideration are already in progress. However, it is increasingly important to coordinate these projects to fit with a larger vision of regional opportunities.

23. Girdwood Nature Center

Description. The development of a nature center on public or private land in Girdwood would showcase a diverse northern rain forest ecosystem and provide a node for exploring the wealth of nearby local trails as well as links to trail systems in Chugach State Park and Chugach National Forest. The addition of a fifth visitor center in the area (after the proposed Alaska Bird Center at Potter Marsh joins the existing downtown APLIC, Eagle River, and Campbell Creek nature centers) would also ensure that there are wildlife and natural resource education opportunities in all corners of the Municipality.

A future Girdwood Nature and Historical Center must differentiate itself from the Forest Service BegichBoggs Visitor Center at Portage. In addition to Girdwood natural areas, a visitor center can reach out to Turnagain Arm and explore its rich diversity. Girdwood boasts the farthest extension of the Northwest temperate rainforest, local creeks support small populations of all five salmon species, beluga whales ply the waters of the Arm, and landscape-scale changes (including sunken trees) wrought by the 1964 earthquake offer additional thematic opportunities.

Rationale. The combination of geography, climate, and location makes Girdwood the ideal place for a nature and historical center. The juxtaposition of the northernmost temperate rainforest, Glacier, Virgin, and California creeks, and an extensive wetland ecosystem support a range of plant and animal communities. Girdwood is a hotspot for birders and botanists. Visitors and “Birdathon” fund-raisers have long raked Girdwood trails and bird-feeders with their binoculars, while plant ecologists and fungi experts comb the forest for species closely associated with both Turnagain and Prince William Sound ecosystems.

The Iditarod Trail draws history buffs and romantics, and Crow Creek Mine (an historic gold mine) draws recreational gold panners. Large, now silent, steam boilers associated with mining at higher elevations along the Crow Creek Trail await those seeking a physical challenge. Crow Creek Trail also returns the prepared hiker and camper to Eagle River and Anchorage through Chugach Mountains and valleys. The trail offers regular black and brown bear viewing, river crossings, and the Eagle River Visitor Center at trail’s end.

Tourism and recreational use continue to expand in southcentral Alaska. Girdwood has a world-class hotel and ski resort and is a natural stopping point for travelers going between Anchorage, Portage Valley, and the Kenai Peninsula. Within a short time, the Alaska Railroad is slated to reopen a station in the lower region of the valley.

Finally, new and planned bicycle and walking trails suggest a future for those visitors choosing to walk the planned Turnagain Trail from Anchorage or points on the Kenai Peninsula. A Girdwood Nature Center would enhance and partner well with this trail system.

Responsibilities. A lead agency or organization needs to emerge; cooperators could include Chugach National Forest, Chugach State Park, the Municipality, or the community of Girdwood. Conservation organization support appears crucial, as might corporate or visitor industry support.

Schedule. This is a longer term project. It is a relatively new idea that needs to gain momentum before funding, design, and construction can begin. This plan is formal endorsement of this project, which should receive additional attention after the Alaska Bird Center at Potter Marsh is completed.

Costs and funding sources. It is difficult to estimate costs when a clear vision of the size and scope of the center have yet to be defined. This is a large project that could cost several million dollars.

Constraints. Location and property options are one constraint, as will be funding and environmental compliance. As noted above, this is a long-term project that requires additional planning to be realized.

Other Supported Wildlife Recreation and Learning Actions

Coastal Trail Connection: Kincaid to Potter Marsh. The planning team supports the idea of extending the Coastal Trail to Potter Marsh, a high priority among Anchorage trail advocates. The team also supports the idea of having that trail connect, in places, to overlooks on the bluffs above the Anchorage Coastal Wildlife Refuge. However, the team did not find consensus on whether the trail should travel through the Refuge, where a multiple-use trail might have negative habitat impacts and encourage wildlife-human conflicts. There is clearly a need to develop more information and consider more public comment about these trade-offs before the trail is designed and constructed.

Interpretation Stations on Campbell Creek Science Center Trails. The BLM has identified and plans to build interpretation kiosks and stations along some trails near the Campbell Creek Science Center, which is supported in this plan.

Interpretation Stations on City Greenway Trails. The planning team believes there are excellent interpretive opportunities along the city’s multi-use trails (e.g., Chester Creek, Coastal Trail, Campbell Creek), and that a few coordinated kiosks or other interpretive stations might be able to reach many Anchorage residents and visitors. These projects were viewed as a lower priority because, although these areas are important wildlife corridors, the primary focus of most of these trails are not wildlife-oriented. The Municipality would be lead on any projects.

Eagle River Viewing Tower. The salmon viewing area along Eagle River (below the Visitor Center) has occasionally been an area with high bear and moose populations. An adjacent viewing tower would offer residents and visitors the opportunity to see these animals more often (because vegetation in the area is thick), as well as provide a “safe haven” if a bear moves directly into the area. Alaska State Parks has proposed and expects to complete the planning for this action.

Eagle River Campground Interpretive Trail. This action would develop a short interpretive trail along the river from the campground. It would feature several overlooks and interpretive stations that would focus on riparian wildlife and ecology. Alaska State Parks is lead.

Glen Alps Interpretive Stations; Middle Fork Campbell Creek Loop Interpretive Trail. Both of these actions would develop interpretive stations along popular trails on the Hillside in Chugach State Park. In both cases, Alaska State Parks is the lead and has planning in place to develop these if funding could be found. CARA may be able to provide funding.

Other Actions

The final two priority actions in the plan are associated with future planning and the need to continue to integrate wildlife management activities among the various local, state, and federal agencies and interest groups. The first identifies the importance of the habitat on the military installations, which could be jeopardized in the future if those bases are relinquished and developed. This action identifies the need for cooperative wildlife and natural resource planning in such an eventuality.

The second identifies the need for wildlife agencies and groups in Anchorage to continue to meet and integrate expertise and resources, and share information even after this plan is finalized. Integrating agency information and activities is not something that just happens on its own; it requires leadership and some level of institutionalization. While the planning team recognizes that the creation of another bureaucracy is less than useful, everyone wants to see the existing ones working together. There is good evidence that many members of the public cannot distinguish between land managing agencies, but they still remain interested in the decisions those agencies make. With this action, we recommend that agencies meet at least annually to review accomplishments and share information, and thus explicitly support a cooperative management paradigm.

24. Planning for Wildlife Habitat on Future Excess Federal Property in Anchorage

Description. Fort Richardson and Elmendorf Air Force Base contain large land areas with significant wildlife habitat value. In the event any of these lands are no longer needed for federal military purposes, several agreements, as authorized by Congress, are in place to determine the future ownership of these lands. The agreements include the North Anchorage Land Agreement (authorized by Section 1425 of ANILCA) and the Cook Inlet Land Exchange.

The North Anchorage Land Agreement identifies a greenbelt along Eagle River, the Eagle River Flats and key moose habitat east of the Glenn Highway for state ownership to protect fish and wildlife values. The agreement also directs the Municipality of Anchorage (MOA) and Eklutna, Inc. to prepare a generalized land use plan for any remaining land in the two military reserves. This action recommends that ADF&G and other wildlife agencies assist NALA parties by defining additional public interest lands for fish and wildlife habitat purposes.

The Cook Inlet Land Exchange directs the disposition of any excess or surplus military lands south of the east-west running line separating Townships 13 and 14 North. ADF&G and other interested wildlife agencies should also be prepared to assist the DNR and MOA in defining fish and wildlife habitat or other natural resource concerns on these lands.

No specific action is required if the installations continue to be actively managed by the U.S. Army and Air Force. If these lands are surplused, however, we believe that a natural resources assessment should be completed before any lands are transferred or disposed. While a NEPA process is required before any Base Realignment and Closing (BRAC) action can be taken, it is unclear whether this would include any examination of public interest in habitat conservation issues. A natural resources assessment is therefore recommended in concert with any BRAC NEPA effort. This assessment should consider wildlife, fish, and other ecological resources, as well as recreation opportunities associated with those resources and environments.

Rationale. Together with Chugach State Park, the two military installations play a critical role in maintaining the ecology, watersheds, and wilderness character of greater Anchorage. These large land tracts, which remain relatively undeveloped and contain large portions of the Ship Creek, Chester Creek, and Campbell Creek watersheds, act as "ecosystem reservoirs" from which many wildlife flow. Military control of public lands adjacent to Anchorage, especially Fort Richardson, has resulted in the retention of healthy functioning ecosystems full of thriving wildlife. In general, the military mission has been compatible with these ecosystems, and recent environmental directives require maintenance of biodiversity and viable ecosystems to ensure natural training settings and scenarios.

The fate of these military lands has been the source of considerable concern in recent years. Although the Army has not announced any intention of relinquishing these lands, Congressional authorization of land agreements suggest that some local development is inevitable if the land is surplussed. This action simply urges careful planning to ensure that any development does not substantially impair the wildlife habitat and function which is currently provided on these lands.

Responsibilities. The lead organization would be ADF&G. Any wildlife or ecological assessment of these lands should also involve Chugach State Park, the Municipality, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and local wildlife interest groups. If the military is relinquishing these installations, their planners and environmental experts may not be in a position to be decision-makers, but could provide valuable expertise. Given the development potential of the area, those interests would also play critical roles in the process.

Schedule. At this time there is no schedule or intention to close or surplus lands from either of these military installations. The North Anchorage Land Agreement directs the MOA and Eklutna, Inc. to prepare a generalized land use plan and to meet annually to review and update the plan. To date, the parties have not prepared this generalized land use plan.

Costs and Funding Sources. No action is currently proposed. Conducting an ecological assessment of the installations would be a substantial cost, but might be covered as part of base closing costs.

25. Formalize Interagency and Wildlife Interest Group Cooperation

Description. This action would recognize the need for continued coordination and integration of agencies and organizations with wildlife responsibilities or interests in Anchorage. It would formally establish annual meetings to review wildlife management actions being undertaken in Anchorage.

Over time, it is hoped that this group would be respected as an entity with special broad knowledge and expertise on wildlife issues in the greater Anchorage area. If this were to occur, the group might be able to help influence and direct development and natural resource decisions in the city.

Rationale. This cooperative planning effort is the first step in coordinating and integrating wildlife management responsibilities among a number of agencies and interest groups. In order to continue the process, however, there needs to be some formalization of the effort into the future. Annual meetings to review actions and successes urged by the plan are a simple mechanism to keep this momentum going.

Responsibilities. Every agency, organization and interested individual that has been involved in this planning effort or who would like to commit to future cooperative planning work would be welcome to participate. However, special responsibilities fall to the lead agencies in this effort, including ADF&G, USFWS, State Parks, BLM, and the Municipality.

Constraints. The press of daily work is a chief constraint.

Actions Considered but Rejected

Large Mammal Predator Enhancement. While additional large predators in Anchorage might help naturally reduce populations such as moose, the planning team recognized that increasing the numbers of bears and wolves in Anchorage is probably not desirable for most residents.

Moose Sterilization Research. Although recent contraceptive technology improvements suggest that some ungulate populations (particularly white-tailed deer) can be reduced through sterilization programs introduced into wildlife feed, the planning team did not think this expensive technology should be pursued for Anchorage’s moose.

Trail connections from Bicentennial to Chugach State Park; convert Tour of Anchorage Trail for summer use. These two suggestions from the public would create additional trails in the Bicentennial Park/Campbell Tract area, but were not supported by the planning team for wildlife purposes. There are extensive existing trails in this area for hikers, and the general concern was that upgraded trails that would encourage additional multiple uses and reduce available habitat would have habitat impacts that would not be offset by the increased wildlife recreation opportunity.

Twin Peaks Overlook Interpretive Station. While the planning team supports the existing trail and overlook on this mountain, they did not feel that additional expenditures on an interpretive station that would increase development levels on this low-use trail were appropriate. The trail currently provides excellent sheep viewing opportunities, but they are primitive in nature.

Trailhead moose warning program; neighborhood bear warning program. Both of these options were rejected as likely having little utility because of the difficulty in providing up-to-date information in a cost effective manner.