Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2020

Rats in Alaska – Keeping Anchorage Rat Free

Invasive Rats & Native Critters

Anchorage may be the largest rat-free port in the Northern Hemisphere. The city is a gateway into Alaska, so when Fish and Game received a picture from Anchorage of a dead rodent in a snap trap, biologists took note.

Wildlife biologist Joe Meehan wanted the body, but the homeowner had tossed it. The picture provided enough clues that Meehan and his colleagues judged it to be a House Mouse (Mus musculus) a non-native mouse originally from Eurasia.

A population of rats has not been documented in Southcentral Alaska. If someone catches a rat in the area, or anywhere they have not been documented, “We want it,” Meehan said. “Put it in a Ziploc baggie, freeze it and get ahold of us.” (More on reporting rats and contact information is provided below).

Rats are established in a dozen communities in Alaska, but not in the Mat-Su area, Anchorage, or on the Kenai. At one point rats were seen at the Fairbanks landfill, but there’s now no evidence rats are established in Fairbanks.

“They’re in Nome,” Meehan said. “They’re not doing well, they get frostbitten, but they are able to hang on, living in utility corridors, buildings and warehouses. They’re surviving.”

Surviving can become thriving with a few good breaks for the rats, said Tammy Davis, who coordinates Fish and Game’s Invasive Species Program. “They may harbor at low levels, and then reproduce quickly if conditions or circumstances work in their favor,” she said. That happened in 2017 in Ouzinkie, a small community 20 miles north of Kodiak. “Weather might have been controlling the population, then we had a couple warm winters and survival was good.”

Meehan said there have been scattered reports of sightings, but there is no confirmed population of invasive rats in Alaska’s largest city. “Maybe those reports are legitimate, but they never got established,” he said. “A newly introduced rat has to find shelter and food and evade predators, or it will die. But you add more rats, and the odds go up of some making it.”

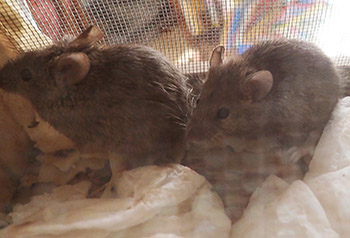

Meehan has seen a lot of rats in his time, dead and alive, but in Anchorage, what he’s mostly seen are muskrats. Alaska’s wild, native rodents – such as muskrats, jumping mice, deer mice, voles and lemmings – are not a problem, and Meehan and other biologists offer advice on how to tell the good guys from the bad guys.

Meehan, as manager of state-designated Special Areas such as the Walrus Islands, is particularly concerned with rats’ impact on wildlife. He helped develop an invasive rodent management plan for Alaska. At least a dozen nonprofits and state and federal agencies have a hand in fighting invasive species. Some are focused on identifying new introductions, others are dedicated to eliminating them where they are established.

Davis said in recent years the focus has shifted from species to vectors – how they get in. “Often, more than one species is being spread by that vector,” she said. That’s particularly true for her primary focus, aquatic invasives; a boat inspection could potentially reveal unwanted stowaway plants, snails, fish, crabs, tunicates, or mussels.

Combatting rats where they are trying to establish a paw-hold comes down to a couple things: eliminating food and shelter. “The harder you make it for rats, the fewer there will be,” Meehan said. “The less clutter there is, the less shelter for them to get into.” It’s a good idea to keep fishing gear such as pots and traps up off the ground. Keep garbage inside sealed containers. Seal off access to warehouses and other places, particularly holes where power and utility lines come in.

Rats eat almost anything; they can chew through metal and cement, and they are excellent swimmers. They carry diseases and do billions of dollars of damage world-wide. Invasive rats have wiped out native wildlife and devastated seabird colonies on countless islands across the globe. In Alaska, that destruction began in 1780 when a Japanese sailing ship went aground on what was subsequently named Rat Island in the Aleutians. Rats are now documented on 21 large Alaska islands, and likely many more small islands, islets, rocks and stacks. But Rat Island has a happy epilogue.

After years of planning by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Nature Conservancy, and Island Conservation, rats were eradicated from Rat Island in 2008. The recovery of native birds and plants has been remarkable, and the name of the island was changed in 2012 to Hawadax Island – the original Aleut name meaning “entry” and “welcome.”

Both the Norway Rat and the slightly smaller Black Rat have plagued humans for millennia. Most rats in Alaska are Norway Rats, Rattus norvegicus, also known as brown rats. The Norway Rat is native to Asia, Meehan said, but since the Norwegians were such wide ranging sailors, they took the wrath for bringing rats to many parts of the world. Norway Rats dig well and excavate extensive burrow systems. The Black Rat, Rattus rattus, infamous for its role in the Black Death pandemic, is also known as the roof rat. It’s more arboreal (hence the latter name), climbs well, and is less tolerant of cold than the Norway rat.

Shemya and Kodiak islands are the only documented sites with Black Rats, and those on Shemya Island out on the Aleutians likely came in on ships in World War II.

Reporting rats

Rats are documented in Dutch Harbor and Adak (and throughout) the Aleutians, as well as Juneau, Sitka, Wrangell, and Craig in Southeast Alaska. A rat in a new area is news. Preventing new introductions is the key objective, rather than responding to known populations.

Davis receives calls about rats, but often they are too vague to be useful.

“I’ll get a call, someone says, ‘I was driving home from the store and I saw a rat,’” she said.

A specific location is important, as is a picture. Scale is very important as size is a big clue to identification – if the rodent is dead in a trap, lay a ruler next to it before taking a picture. The actual rat is best of all. Turned in to Fish and Game or other rat-combatters, the carcass will likely end up in the hands of Link Olson for positive identification.

Olson is the Curator of Mammals at the University of Alaska Museum of the North (UAMN) in Fairbanks, and he’s a researcher and a biology professor at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. “A rat in the hand is worth 20 in the landfill,” he said.

He added that definitive identification as well as a slew of other potentially useful information about parasites, reproductive condition, disease, diet, and countless other attributes—collectively referred to as an “extended specimen”—can be studied in perpetuity when intact specimens are archived and curated in a research museum such as UAMN, which is the State repository for such material.

“Once they’re prepared as specimens and catalogued in our facility, they serve as permanent records that qualified scientists from around the world will be able to study forever,” he said, noting that “much—if not most—of what we know or think we know about small mammals stems from specimen-based research, and our mission is to maintain and grow the State’s reference collection.”

In addition to the Norway and Black Rat, biologists are on the lookout for the Tanezumi Rat, a close relative of the Black Rat that’s established only in a few places on West Coast.

The Port of Alaska in Anchorage

Stowaway rats on ships account for the wide distribution of rats across the globe. The prominence of Anchorage as a center for shipping in Alaska merits vigilance there.

“Anchorage is such a hub; if we get rats in Anchorage, they may get into cargo going out to villages and other places,” Meehan said. “Rats would not be good for Anchorage area wildlife, and if we get rats at natural areas it could really impact wildlife, especially sea birds.”

Last year the Port of Alaska in Anchorage handled 4.3 million tons of cargo. Billions of dollars in goods moves through the port every year – half of all freight coming into Alaska. Jim Jager is the Director of Business Continuity and External Affairs for the port. I asked about rats at the port and what efforts are in place to keep them out.

“There’s no sign we have a rat population,” he said. “I’m not saying we’ve never had a rat, one may get to shore occasionally, but it doesn’t get far.”

Caution and vigilance contribute to that. All internationally-flagged vessels – including cruise ships – follow standard pest protocol, including Customs and Border Patrol checks, and rat guards on all lines.

The Port of Alaska and port-tenants all have some sort of pest monitoring/control, primarily for mice and voles, in their buildings that would likely reveal the presence of rats. Jager said in his role as Facility Security Officer, he’d find out quickly if a rat was seen.

Virtually all Port of Alaska’s food cargo is carried by domestic shippers from a domestic port (Tacoma), in containers designed to be rat-proof, and there is virtually no on-port food/cargo storage. The average container “dwell time” is less than 17 hours – a typical container is off-loaded and on its way to a final destination less than 17 hours after ships arrive in Anchorage, often much faster.

“They aren’t sitting there waiting for rats to get into them,” Jager said.

Also working to Anchorage’s advantage is the nature of the port’s inbound international cargo, mostly fuel and cement, which is not particularly attractive to rats.

The 125-acre Port of Alaska is physically segregated from downtown Anchorage and neighborhoods that could provide attractive rat habitat. A stowaway rat jumping ship at the port will find a healthy population of potential rat predators waiting on shore – bear, lynx, fox and eagles are all in the area.

“This is not a friendly ecosystem for a lonely rat,” he said. “If a lynx doesn’t get you a fox might.”

Released Pet Rats

Meehan said over the past 15 years or so, he and former Area Biologist Rick Sinnott investigated about a dozen rat reports in Anchorage (including muskrats brought into the office) and found that only a couple were actually rats.

“Both were obviously released pets,” Meehan said. “One was at the airport, the other a local park.” They were piebald, a type of white and brown spotted coloration common in pet rats. “They were not all brown, which you’d expect from a wild rat.”

Alaska law allows white rats (lab rats, Rattus norvegicus var. albinus) in the state as pets, but cities can and do enact stricter measures.

“Anchorage has an ordinance that says you can’t possess rats at all, period. Unless you get a permit for university research or something like that,” Meehan said. “No pet rats are allowed at all.”

Is that really a rat?

Muskrats

“We hear about rats the size of cats, where people are sure they’ve seen a rat when it’s a Muskrat,” Davis said.

Muskrats are native to Southcentral Alaska, and they are found in the Interior all the way to the Brooks Range, and Olson noted that two summers ago Muskrats were found north of the Brooks Range along the Dalton Highway corridor.

Meehan said Potter Marsh has a ton of Muskrats, as does Conner’s Bog. They are common around Anchorage and mistaken for rats.

“A Muskrat is not going inside for same reason a rat will, it’s just wayward. A rat is looking to find a home, the Muskrat just wandered in,” Meehan said. “Usually when we get a report of Muskrat, people are seeing them outside, in the street or yard.”

When rats come inside, it’s quite deliberate. “Rats want your food and a nice warm safe place to have babies,” Davis said.

Meehan said when he gets a report of a rat sighting, he looks at the address to see how far it is from a wetland area. If it’s next to a ponded area, it’s probably a Muskrat. A Muskrat might also travel through storm water drains, and he’ll also check to see if that’s also a possible route.

Muskrats are bigger and bulkier than Norway Rats, with a body 10 to 14 inches long plus an 8 to 11 inch-long tail. That tail is distinctly flattened, as the aquatic Muskrat is a swimmer. Meehan said that’s the first thing to look for.

“The Muskrat’s tail is flattened from side to side, so get a good look at the tail.”

Mice

Wild mice sometimes come indoors, but Meehan said the majority of mouse problems in Alaska are in settled areas, and involve the House Mouse. In some cases, mice are more of a problem for people because they are much smaller than rats.

“They can get through a hole smaller than a dime, and they’re harder to eradicate,” Olson said. “They are human commensals. They’ve evolved with humans over the past several thousand years and they’ve got our number.”

Olson said there are no kangaroo rats in Alaska but there are jumping mice. They are sometimes caught indoors in traps, but Olson said more often in the Interior, people see them when a cat catches one and brings it in. They are three to four inches long, with big hind feet and very long tails – longer than their body.

“People don’t realize we have jumping mice in Alaska,” Olson said. “We know next to nothing about them in Alaska. People talk about mice and voles hibernating, but they don’t - they are active all year long, as are shrews. Jumping mice do hibernate.”

Deer Mice (Peromyscus), the most common and widespread wild mouse in North America, are expanding their range in Alaska. That’s true of other animals as well - beaver, moose, deer, and fisher, for example.

“We have the first picture ever taken of a red squirrel in Nome, hundreds of miles from the nearest previously documented record,” Olson said. “Is this climate change, anthropogenic [human-mediated] expansion, or natural range expansion that’s still happening following the retreat of the glaciers? Parsing these and other possible causes isn’t as straightforward as you’d think.”

Biologists are documenting the movements of wildlife into new areas and watching how that might affect other wildlife. Range expansion is relatively slow, but introductions can lead to a population explosion. The impacts that rats have is well known to be negative, and they are not welcome when they arrive.

Report rats (by phone Invasive Species Hotline: 1-877-INVASIV (1-877-468-2748); by email

or online

Stop rats website

Invasive Species – Norway Rat

Fish and Game Invasive Species Website

Norway Rat profile, more resources: Wildlife and people at risk: A plan to keep rats out of Alaska (PDF)

University of Alaska: Museum of the North

About the Port of Alaska

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild! radio program. He managed the lab rat breeding facility in college for the biology and psychology departments and appreciates non-invasive rats and native wild rodents.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.