Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2019

Counting Rockfish with Sound

Black rockfish hydroacoustic surveys

Along the coast of Kodiak Island and the Alaska Peninsula, schools of rockfish swim the green waters surrounding submerged pinnacles and reefs. Biologists identify and count these fish using a remarkable set of tools, and use what they learn to make sure the fishery is sustainable.

Black rockfish are the main species of interest, but dusky rockfish and dark rockfish are also common. Black rockfish favor nearshore rocky habitat and relatively shallow water, and they have an affinity for specific areas. “They school over these areas and have a high site fidelity to certain pinnacles,” said biologist Carrie Worton. “That makes them vulnerable to localized depletion. They do move, but they like their spots.”

Biologists have seen these schools – hundreds of fish hovering over striking white Metridium anemones, sprouting like tall mushrooms from the rocky seafloor – using underwater video cameras suspended below their research vessel. Aptly named quillback, yelloweye, tiger and silvergrey rockfish are mixed in with the black rockfish, with the occasional chunky prowfish prowling near the bottom.

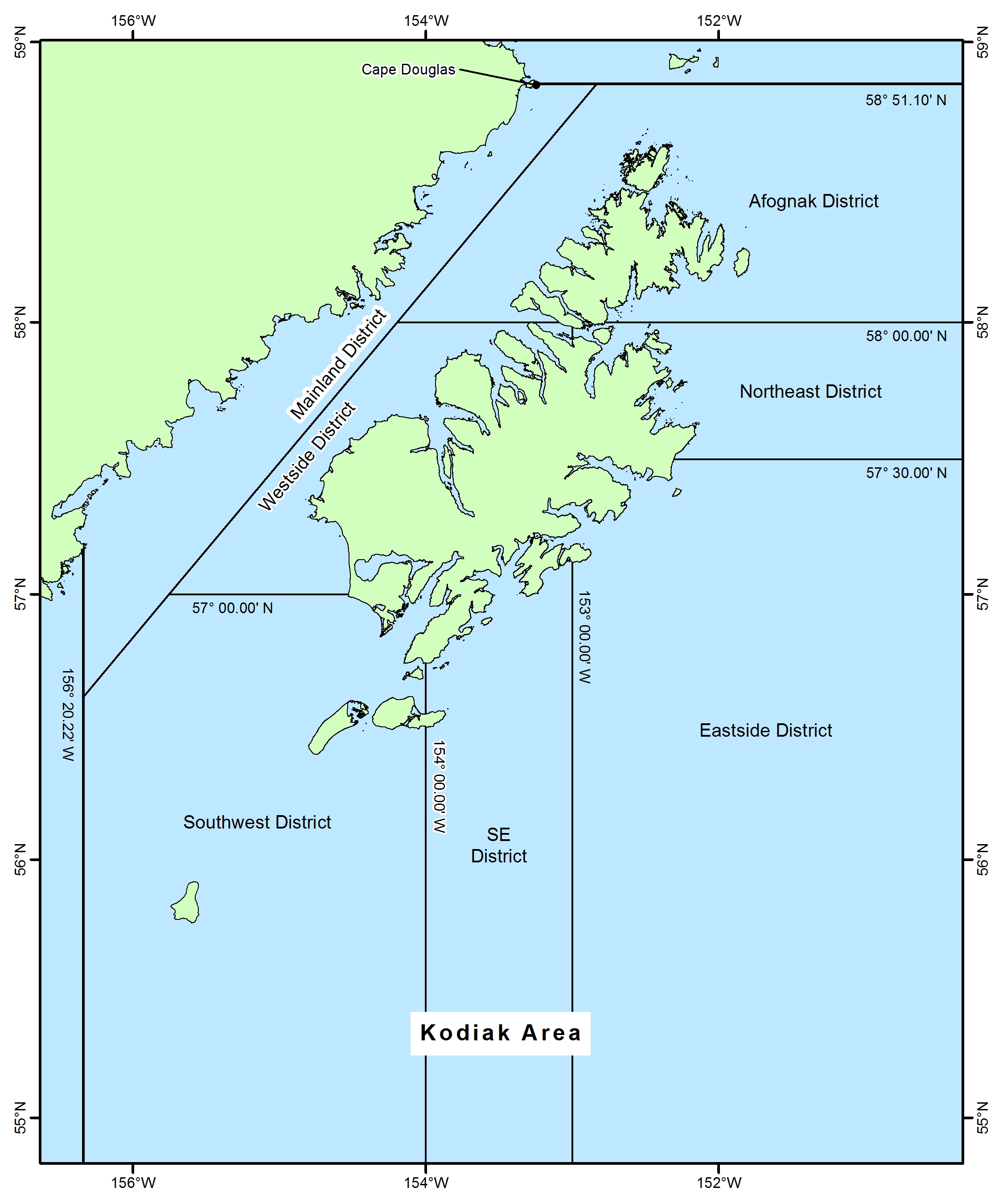

Kodiak-based fishery biologists have identified prime rockfish habitat and they focus their attention on these areas, known as stations, for rockfish surveys. More than 200 stations have been identified along the coast of Kodiak Island and the southern coast of the Alaska Peninsula just west of Kodiak Island.

Rockfish are managed in seven districts in the Kodiak area. Biologists set annual Guideline Harvest Levels for each district, based largely on an average of historical commercial harvests, with an overall total of 120,000 pounds of black rockfish per year across all seven districts.

Black rockfish in the Kodiak Area average about four pounds, so roughly 30,000 fish are harvested annually in the commercial fishery.

Carrie Worton is a fishery biologist and serves as the project coordinator for groundfish and shellfish research in the Westward region, the Kodiak Island area and the Gulf of Alaska. She and fishery biologists Rob Baer and Philip Tschersich (pronounced bear and chair-sik) conduct annual rockfish surveys, process the data they collect, and use it to study and manage rockfish.

One goal of rockfish research is to improve the management strategy. Worton said that the original Guideline Harvest Levels were based on historic harvests, and biologists are working to develop an abundance-based management strategy. Such a strategy would address uncertainties regarding sustainable management of the fishery and help prevent localized depletion. The hydroacoustic surveys are an important part of this.

Surveys are conducted aboard the Fish and Game research vessel K-Hi-C, a 42-foot converted seiner, homeported in Kodiak and skippered by Daniel Wilson. A smaller 26-foot vessel, the research vessel Instar, is also used for day trips closer to town.

Looking underwater: hydroacoustic surveys and underwater video

“We’re using sound to detect fish in the water column,” Worton said. “We have a sophisticated fish finder, an echosounder. It emits a sound that hits a fish, or something of a different density, and it sends back a signal. It amplifies it, analyzes it, and displays it.”

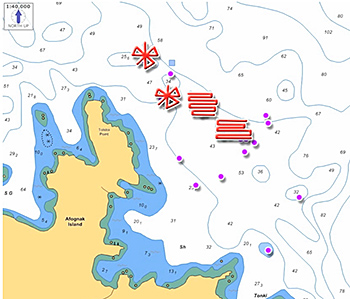

Tschersich said a typical fish finder displays a two-dimensional view. “Our transducer can see in three dimensions in the water - and that allows us to group individual echoes into fish, provided that they are far enough apart from each other. The black rockfish we study generally have enough space between them that we can count individuals. That’s not true for fish like herring, that are grouped tightly together.”

But black rockfish are not the only species schooling around those pinnacles.

“We have to figure out what we are counting, and we use video cameras to identify the fish,” Tschersich said. “We suspend the underwater video camera system over the side of the vessel on a cable and drift it just off the sea floor through the fish schools.”

All the video is recorded to hard drives. The useful footage acquired from a station is reviewed by an experienced biologist (Tschersich) who identifies and counts the rockfish species, after which a proportion by species is calculated. This enables biologists to estimate the numbers of black rockfish in the overall survey.

The camera footage does not need to replicate the exact survey transects, as the rockfish observed in the video represent the total rockfish in the survey area.

Worton said biologists are working on a new stereo camera system they hope to deploy soon. “This will be more sophisticated and allow us to take measurements of the fish,” she said. “It will be a separate sampling method, just to get length data.”

The surveys start in May and generally run through the summer into September. Stations in all seven districts are surveyed.

Biologists delineate the boundaries of the stations and establish transect lines within the station, either lines based on a center point, or back-and-forth transect lines 50-meters apart. A long underwater reef would be well-suited to transects running across the reef, and a large pinnacle would be better suited to survey lines radiating from the center of the pinnacle.

A 500-meter-wide station might have nine transect lines 50-meters apart. The survey vessel operates at 4 ½ knots, so depending on the size of an area, a survey might take 20 minutes or several hours. The widest station is 1.25 km in diameter and has 25 transects in it.

After determining abundance, biologists create a biomass estimate and the results are incorporated into management decisions on Guideline Harvest Levels for each of the seven districts. Department biologists hold Guideline Harvest Level meetings in November or December, then the fishery opens in January. It closes in each district by Emergency Order once the Guideline Harvest Level is met. Worton said that’s generally met by May and June.

The Fishery

A Kodiak-based fleet of about a dozen boats catches most of the rockfish in the commercial fishery. It’s a jig gear fishery, both handline and mechanical jigging machines are allowed. A vessel is limited to no more than five mechanical jigging machines per vessel and no more than 30 hooks per line.

There are trip limits, and fishermen can’t sell more than 5,000 pounds in a consecutive five-day period.

“The canneries like to have the fish within three days, so they’re delivering quickly,” Worton said. “They can catch their limit in a day, if they are on the bite. We have several processors in Kodiak, and they process everything.”

She added that there’s an allowable bycatch in other fisheries. If someone is fishing for cod, for example, they are allowed to catch some rockfish.

The market has largely been whole frozen, and Korea is a major buyer. There is also a small fillet market.

To get a sense for the scale of the fishery, the NE District is the one closest to Kodiak, and its Guideline Harvest Level is 20,000 pounds. That’s about 5,000 black rockfish. But even more black rockfish are caught by sport anglers in that same area.

Rockfish fishing is popular with sport anglers. Anglers catch rockfish from shore, but the vast majority are caught from boats. Chiniak Bay near the town of Kodiak overlaps the NE District, and about 8,000 black rockfish are caught there annually by sport anglers.

The sportfish harvest has grown significantly over the past decade, and Worton said that has become an important aspect of management. “In recent years, we started to collaborate with the Sport Fish Division on black rockfish research to ensure we incorporate all user groups and information into our region’s stock assessment of black rockfish,” she said. “With Sport Fish Division’s support, we’ve been able to continue our survey work and collect important life history information on the species.”

Charter captains record catch information for their guided anglers in their logbooks, and that is shared with sport fish division biologists. Dockside surveys of anglers and biological sampling also provides data: species of rockfish, length, weight, age, and sex. In addition to numbers of rockfish caught, and species composition, that enables biologists to look at trends over time – changes in age structure and size.

Tyler Polum is a fishery biologist with the Sport Fish Division, based in Kodiak. He said there are about 20 sportfishing charter boats fishing out of Kodiak that are very active, some that are less active, and 50 or 60 operating out of remote lodges on Kodiak Island – so about 100 charter boats island-wide.

“Around 2005 the sport harvest of rockfish started to really build, driven by charter fleet,” Polum said. “Then around 2010 unguided angler harvest really started increasing as well.”

Chiniak Bay is the primary area for the sport fish harvest, and biologists responded to the increasing pressure by modifying bag limits. Prior to 2011, the bag limit for rockfish was 10 per day. That was reduced to five per day, and only one could be a yelloweye rockfish.

“In 2017 we went back to the Board of Fish because the sport fishery was still growing, and most of the fish were coming out of this area right near town, Chiniak and Marmot bays,” Polum said. “The bag limit was reduced to three per day from this area, and five per day for the rest of the island.”

He said biologists are working on a proposal to update the management plan for the sport fishery in 2020, looking closely at both the commercial and sport fisheries in the Northeast District area.

“The big take home for this is we’ve been managing these two fisheries independent of each other and they are the same fish,” he said.

Harvest data from both fisheries, combined with insights gathered at sea by biologists looking at rockfish in their element, is providing valuable information for fishery managers.

“This is why the hydroacoustic survey is so important,” Polum said. “Rockfish are slow growing and long lived. Given their life history you need to be conservative in managing them.”

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.