Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

July 2019

New Deer in Alaska

Mule and White-tailed Deer Colonizing new areas

The big buck posed beside the road at the edge of the trees. I slowed as I drove past and took a good look - it was a mule deer, the larger cousin to the familiar Sitka black-tailed deer. I was outside of Carcross, British Columbia, on my way to Skagway, and this was my first realization that mule deer were just across the border from Alaska.

Alaska hunters will discover a new page in the 2019-2020 hunting regulations (“Deer in Alaska” p. 28), which describes mule deer and white-tailed deer, two historically non-native species that are now moving into Alaska. Wildlife managers with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game are monitoring this range expansion, and the new regulations outline how Alaska hunters may harvest mule and white-tailed deer in those areas where they might be encountered.

Fish and Game biologists want tissue samples from any white-tailed and mule deer harvested in the state, and welcome any reports (especially with photographs) of these deer seen in Alaska. Deer identification and contact information are provided in this article.

Deer on the move

Changes to the American landscape over the 20th century benefitted deer. Agriculture, road-building, forest practices, climate change, as well as improved game management and predator reduction, all helped deer multiply and expand their range. Historically, white-tailed deer were (generally speaking) found east of the Rocky Mountains (white-tails are Odocoileus virginianus - also called Virginia deer). Mule deer were western deer. Black-tailed deer are a smaller-bodied subspecies of mule deer, found on the West Coast. Columbia black-tailed deer inhabited Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, and Sitka black-tailed deer inhabited B.C. and Southeast Alaska. There was range overlap and even some hybridization of the species, but ranges of deer really expanded in the second half of the 20th century.

Mule deer and white-tailed deer have been steadily moving into new areas of western Canada, something wildlife biologists there are closely monitoring. That establishes source populations within striking distance of Alaska. River valleys are access corridors for wildlife, as are roads like the Alaska Highway Corridor.

Given that, it’s not surprising that there have been scattered reports of mule deer in the Tok area going back decades. Mule deer have recently been documented in other border-area communities like Chisana and Eagle. In 2013, three mule deer were reported north of Delta Junction. In May 2017, a mule deer was killed by a car outside Fairbanks, and mule deer have been photographed in North Pole, and near the Fort Knox Mine.

These areas of Eastern and Interior Alaska historically did not have deer at all, and any deer seen in these areas are likely to be the new arrivals.

Black-tailed deer are found throughout Southeast Alaska. Deer from Sitka, on Baranof Island, were transplanted to Southcentral and Kodiak Island in the 1920s, establishing populations there.

In Southeast Alaska, a mule deer was recently photographed near Skagway.

The story is similar for white-tailed deer, although they’ve not yet been documented in Alaska.

“White-tailed deer have been expanding west for a long time,” said Dan Eacker, a Fish and Game deer research biologist based in Douglas. “They’ve really spread into western states, and even up into Alberta. They have an active culling program in Alberta, because of concerns about apparent competition with woodland caribou.”

State wildlife biologist Roy Churchwell serves as the area biologist for Juneau and northern Southeast Alaska. He said white-tailed deer have been seen near the southern-southeast community of Hyder, and in early July, a white-tailed deer was reported by a reputable source near Haines.

“They are basically within spitting distance of the border,” he said.

Why the new regulations?

The primary objective of the new harvest regulations is to provide Fish and Game with tissue samples. These are: the head with the brain; the heart with the lungs attached, the liver; a fecal sample (pellets), a hoof, and the hide. The hide is important because of ticks; Fish and Game and other state partners are monitoring the potential influx of non-native ticks to Alaska, and ticks on wildlife should be collected. Call Fish and Game or check the website for more information and details. Contact information is at end of the article.

Ryan Scott, the assistant director of the Division of Wildlife Conservation, said after the sample organs are provided to Fish and Game, hunters can keep the meat. After brain tissue samples have been taken from the head, the department can return antlers to a hunter.

“This is not about eliminating these deer in Alaska,” said Scott. “We recognize that deer are expanding their range, and have been expanding their range through B.C. and the Yukon for a long time.”

Scott added that documenting the presence of these deer as they move into the state is valuable. Knowing that these deer are here, and getting these samples, is really important, he said.

Requirements have been modified since the Hunting Regulations went to press. Page 28 states that hunters should bring in the entire carcass, but that is not necessary. That might be practical in some situations – in the Fairbanks area, for example, a hunter could drive to the Fish and Game office on College Road with the carcass and samples could be collected there. If a hunter in Skagway harvests a mule deer, it makes more sense to provide biologists in Juneau with the important organs and not try and ship the entire carcass.

The “Deer in Alaska” page also states that hunters must, “…contact the nearest ADF&G office prior to harvesting the deer…” That is not necessary. Wildlife managers do not want hunters mistakenly shooting Sitka black-tailed deer; and they want hunter to collect and provide the appropriate samples, and not simply field dress the animal as they normally would.

Deer hunters are encouraged to contact Fish and Game with any questions, especially hunters afield in the areas where the deer have been documented, or where these deer have access to Alaska via transboundary rivers from source populations in Canada. These areas include Haines and Skagway, Hyder, and the Yakutat Forelands (Game Management Units 1 and 5); the areas along the Alaska Highway corridor from the border east of Tok to Fairbanks (GMU 11, 12, 13, and 20); and a bit further north in GMU 25.

Since black-tailed deer are a subspecies of mule deer, which are well-established in Southeast Alaska, hunters in Southeast should be particularly attentive to distinguishing characteristics.

Know Your Deer

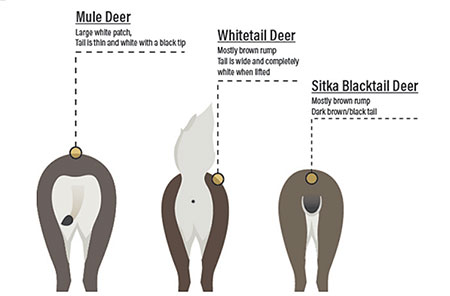

The key things to distinguish between the three deer species are size, antler configuration, and the shape and color of their tails. Behavior also offers clues.

“The tail is one thing that really differentiates them, and body size,” said deer biologist Dan Eacker. “Whitetails put their tail up in the air like a flag when they sense danger - they flip that tail up, then they go. It’s a big, bushy, feathery white tail. Mule deer have a small little rope-like tail. The black-tail has a bushier tail than a mule deer.”

The flight response offers another behavioral clue. Mule deer and black-tailed deer share a response that’s different from white-tail deer.

“Mule deer do this thing called a stot, where they bound on all four legs.” Eacker said. “Gazelles do it, pronghorns do it, they bounce straight up in the air on all four legs. You don’t see whitetail deer do that, white-tails gallop more like a horse. It’s a noticeable behavioral difference, how they react to danger or a predator.”

Sitka black-tailed deer are the smallest of the three, mule deer the largest. That’s helpful if you see a really big deer, but not so much if you see a 90-pound doe. Mule deer are named for their large ears, but again, that’s a comparison trait between the species.

Mule and black-tailed deer antlers branch in a Y-configuration, a four point buck having two “Y” points on two beams. White-tails have individual tines growing off one main beam.

What are some issues with incoming deer?

Dan Eacker said the big issue with incoming deer is disease transmission, especially chronic wasting disease (CWD).

“It would be devastating if that got into our deer herds here,” he said. Eacker moved to Alaska in 2018 from Montana, and said Montana just detected CWD in mule deer in 2017. Wildlife managers with Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks have designated the areas where the disease is present as “CWD Management Zones,” and they have a management plan in effect.

CWD, a disease fatal to wildlife, was first detected in America in Colorado in 1978. It has since spread, and it’s now present in 26 US states and three Canadian provinces - and it continues to spread to both free-ranging and captive ungulate populations. Although it’s primarily found in deer, it can also infect moose, elk, caribou and reindeer.

Another issue is the potential arrival of a moose parasite, the moose winter tick. State wildlife veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen said that almost half of the mule deer surveyed in the Yukon were carrying the moose winter tick. Those deer, coming into Alaska, have the potential to drop ticks in Alaska and infect our moose population.

White-tailed deer tend to be quite tolerant of people, more so than mule deer or black-tails. Eacker said all deer species are capable of habituating to people, but overall white-tails are especially good.

“They are very tolerant of people and human behavior and as a result, they can be a nuisance in a lot of places. They are highly adaptable. They get to high densities, and then they get hit by cars a lot, they eat gardens up, and they become a management problem. They have the potential for really high population growth rates.”

More deer support more predators, which can affect other species. Eacker said the growing white-tail population in Alberta, Canada, led to an increase in wolves, which then also targeted woodland caribou, which wildlife managers want to protect. Mountain lions are expanding their range in British Columbia and the Yukon Territory, something biologists attribute the expanding range of mule deer.

White-tailed deer’s high adaptability and tolerance for human activity means that in some areas, they can outcompete native ungulates, thriving at the expense of native mule deer, moose and caribou.

Deer in Context

Animals have been colonizing Alaska for centuries. Sitka black-tailed deer colonized Southeast Alaska from the Pacific Northwest as the glaciers receded about 10,000 years ago, and they were followed by predators – wolves. Coyotes colonized Alaska during the 20th century, and their range expansion was benefitted by the same factors affecting mule and white-tailed deer.

Fish and Game recently adapted regulations to accommodate another species’ expanding range when fisher, large cat-like weasels moved into Southeast Alaska from British Columbia. Since they were first documented in the late 1990s in the Juneau area, more than two dozen fisher have been trapped in Southeast. In 2013 an open season was created for fishers, in part to encourage reporting.

Within Alaska, moose and beaver are expanding their ranges, moving north and west into areas where they were historically not found.

In addition to deer provided by hunters, Fish and Game welcomes any photographs or reports of mule and white-tailed deer sightings in Alaska.

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News. He grew up hunting mule deer in Eastern Oregon and Columbia black-tailed deer in western Oregon.

More information:

Deer in Alaska in Hunting Regs: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/regulations/wildliferegulations/pdfs/deerid.pdf

Submitting a tick found on an animal

Contact info For Wildlife Conservation:

Fairbanks: (907) 459-7206

Tok: (907) 883-2971

Delta Junction: (907) 895-4484

Douglas: (907) 465-4265

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.