Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

June 2012

Ticks in Alaska

Ticks, small blood-sucking arachnid parasites, are not well-known in Alaska. But Alaskans should be on the lookout for ticks this summer.

“All too frequently I hear from both vets and the public, ‘We don't have ticks in Alaska,’" said Kimberlee Beckmen, a veterinarian with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

One species, generally found on squirrels and hares, is common in Alaska and native to the state, but those aren’t the problem. It’s the introduction of non-native, potentially disease carrying ticks that’s a concern.

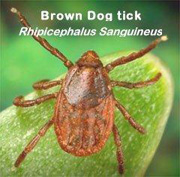

Beckmen was recently sent ticks from Juneau, Sitka, Anchorage and other Alaska communities for identification. Beckmen consulted with an expert in Georgia who helped identify the different ticks, which included the American dog tick, the brown dog tick and the Rocky Mountain wood tick. Most were found on dogs, and all the dog ticks were non-native. It was the first time they’d been identified in the state.

“We don’t have dog, deer or moose ticks in Alaska, and we don’t want them here,” she said. Ticks carry Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tick paralysis, Lyme disease, Q-fever, tularemia and other diseases - and many of the diseases affect dogs, wildlife and people.

One tick came from a dog in Sitka, a dog that had just come up from Oregon. That tick was a species that carries Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Beckmen said. One tick came from a dog that had never left Juneau. Two more ticks came from dogs that had never left Sitka.

“Veterinarians and the public are not generally aware that we can have these ticks and tick-borne diseases,” Beckmen said. “Last week I had a vet ask me about a strange case in a dog that involved paralysis, and I said he should consider tick paralysis – and that was not even in his mindset, it’s not something Alaskan veterinarians would think to look for."

Ticks can come to Alaska on dogs, and on farm animals like cows and horses.

“We have had them come up on people,” Beckmen said. “People driving up or flying up with pets can bring the ticks up here.” Last July, a woman whose friend returned to Fairbanks with his dog from Wisconsin and discovered she was carrying a tick, presumable that was transported on the dog.

Beckmen said livestock are required to be inspected when they’re brought into Alaska. “If you’re bringing a cow up to Alaska, it has to be examined by a veterinarian for ticks.”

That’s not the case with pets, so it’s important the owners inspect or treat their pets.

“Our current climate can support the life cycle of many of these ticks, once they arrive,” Beckmen said. “The only thing to prevent this is to keep them from arriving. People should look for ticks and treat their dogs with a tick repellant if they are coming up. I use a product on my dog that helps repel mosquitoes, but it also repels ticks and fleas. There are several different products available from veterinarians. If people have friends coming up to visit, make sure they alert their friends they should use a tick treatment on their dog before they drive up.”

Treatments are easy. A few drops of the product are applied to the skin along the dog’s back, and the treatment is good for many weeks. Beckmen said that flea and tick collars do not work well.

Ticks can survive and overwinter here, Beckmen said, and with a changing climate, additional species of ticks may find Alaska suitable. One species, Ixodes angustus, is common on hares and squirrels. “That’s not a concern because it’s been here, it evolved here, and we aren’t asking people to report those. But we are really on the lookout for the moose winter tick. That can come up on somebody’s horses, on cattle, bison or elk, or on free ranging wildlife – it is found in Canada and the lower 48.”

Research has shown that the moose winter tick, Dermacentor albipictus, can reproduce and survive in Fairbanks and Palmer. “If it is introduced, it will likely become established,” Beckmen said.

The moose winter tick is a very serious health issue and can kill moose, and calves are especially vulnerable. The ticks cause the moose to itch and scratch, breaking and losing substantial amounts of hair. A moose with typical infestation can have tens of thousands of ticks and experience significant blood loss.

Beckmen detailed the disturbing amount of moose blood an infestation of ticks can suck in a couple months. An adult moose has about 32 liters of blood in its body, and an infestation of ticks can consume 40 liters of blood in two months – meaning the animal must more than replace its entire blood volume

Blood loss, heat loss, and spending more time scratching than foraging, combined with the hardships moose experience in winter, take a lethal toll.

“They often die in a state of starvation in January or so – and the hair loss is at its most obvious, that’s why they call it winter tick,” Beckmen said. “It’s naturally found in areas like Alberta, but it’s moving north as the environment is warming up farther north.”

The Department of Fish and Game encourages Alaskans to submit specimens if they find ticks. Contact dfg.dwc.vet@alaska.gov or bring ticks to your local ADFG biologist. Ticks can be brought in live, frozen or preserved in alcohol, in a tightly sealed container please.

“The biggest thing is for Alaskans to be aware and on the lookout for ticks,” Beckmen said. “Those ticks can make dogs sick and make people sick.”

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild radio program

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.