Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2011

Operational Planning:

Successful Research for Sound Fishery Management

Every year hundreds of technicians, biologists, and others are in the field collecting the data that fishery managers need to make informed decisions to protect and improve the state’s recreational fisheries resources.

If you’ve gone fishing any time in the recent past you’ve undoubtedly reaped the benefits from the data that these researchers have collected. Sometimes the research leads to restricting or even closing a fishery to protect the fish population for future generations --- not only of the fish themselves --- but for future generations of anglers. Sometimes the research leads to liberalizing the bag limits, opening more days in the fishery, or identifying new fishing opportunities for anglers to enjoy.

In order for the data collected by these researchers to be useful for fishery management decision-making, the science of not only fisheries biology but also statistics are used by these researchers to design and implement their research plans.

Since 1985, the Division of Sport Fish (DSF) within the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) has followed an operational planning policy for all research conducted within the division. Early on there were some growing pains followed by a period of maturation. In 1989 the policy was reaffirmed and formalized in a memorandum from Norval Netsch, the director of the division at that time, which included the following specific policies related to operational planning:

Every project that is budgeted, and in which a parameter is estimated or a hypothesis tested, must have an operational plan.

There must be an operational plan for every year that a budgeted project exists.

Operational plans must be signed by the project supervisor(s), the management biologist(s) responsible for sport fisheries in the area where the project is being conducted, the consulting biometrician from the biometrics section, the regional research supervisor, the regional supervisor, and the biometrics section supervisor.

The operational plan for each project will clearly identify the products that the project will produce and the cost of producing the products will be incorporated into the budgetary summary section of the plan.

The purpose of these policies were not directed at identifying the needs of sport fisheries management, but they were directed at achieving the goal I outlined above, namely:

Insure that information obtained through research is accurate enough, precise enough, and appropriate for good management of sport fisheries.

Assuming someone would agree that this goal is desirable … the same level of agreement may not be met when it comes to exactly how to reach this goal. There are likely a wide variety of approaches one might use to achieve this goal. I will describe the approach implemented within the Division of Sport Fish. I’ll highlight some of the features of the operational planning process as well as its successes.

So what exactly is the operational planning process? It can be described as follows:

• The process is a cooperative venture among researchers, research coordinators, regional supervisors, statisticians (aka biometricians), and others; its product is the project operational plan.

• The process begins by identifying fisheries and fish stocks and/or their habitats for which new or additional information is needed to continue or begin good management. This information could be about fish abundance, stock identification, instream flow, habitat characteristics, harvest, catch, public opinion, and/or other data.

• With directions from supervisors and assistance from biometricians, biologists decide how good this information must be before it can be used for informed management.

• Methods and means whereby this new information is to be obtained are then chosen. Mark-recapture experiments, creel surveys, public surveys, radio-telemetry, counting towers, and sonar are examples of these methods and means.

• Once these methods and means have been established, the biometrician uses the science of statistics to set the sampling levels that will produce information of the necessary quality.

The roles of the participants in this process often blur. At times the project leader has insights on management, the biometrician on research, and the manager on biometrics. Each participant brings his or her unique perspective regarding the planning process due to their experience, education, and responsibilities, contributing a fresh outlook and new perspective in other areas that can add vitality to the planning process.

The written operational plan is the vehicle with which cooperation is organized. Its writing forces the participants to think about what they propose to do. The operational plan is also a sampling schedule for the field season, a detailed history of planning, and the tangible evidence that planning has taken place.

In our plans precise language is used to state the objectives for each research project. Specifically the objectives are generally introduced with the infinities “to estimate” or “to test” or “to count”. Phrases such as these have precise statistical meanings that can the later be matched to a specific method of field sampling or experimental design that is founded on good fisheries and statistical practice. Additionally, each objective has corresponding language that defines the quality of the information needed for good management decisions. These “objective criterion” are then used to set sample sizes, and later used to judge the success of a research project.

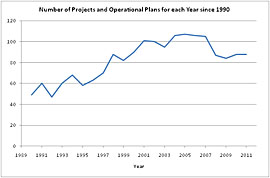

Since the early days of the operational planning process in the Division research project biologists have been partnered with a consulting biometrician to develop each project operational plan. The number of plans and projects have grown with some fluctuation over the last 24+ years since initiation of the process. The fluctuations are primarily due to the changing needs of fisheries management in the state over these many years, I repeat that the operational planning process does not set the needs of sport fisheries management, but is directed at successfully providing the information necessary for successful management.

I have described the operational planning process as a cooperative venture. The common ground for all parties in the planning process is the tandem missions of the department and the division. This common ground means that the role of the biometrics unit is not necessarily as a regulator, but as a partner in the planning endeavor. Note however, that within the Division of Sport Fish the unit responsible for the biometrics is a statewide unit with separate lines of supervision than that of the research biologists for each project. This separation of supervision holds some advantages to achieving the overall goal of the process, in that it allows for a research environment wherein valid differences of opinion or judgment regarding the specifics of the research plan can be allowed to be fully explored without one person’s position necessarily taking precedence over the other. Differences of this sort are generally worked out to both the research biologist’s and consulting biometrician’s satisfaction without intervention by supervisors, but when necessary the separate lines of supervisors can and do step in to resolve differences in order to successfully achieve the goals of the project while still following the operational planning policies.

Another advantage to the separate lines of supervision for the biometrics unit derives from the ability to match biometric expertise with project-types regardless of location of the project. In other words since the Division of Sport Fish biometricians are centrally organized they can and do work on projects throughout the state. A positive ‘side-effect’ of this central organization is that turnover in biometrics staff doesn’t necessarily translate to lack of help for the projects previously assigned to a vacant biometrician position.

The successes of the operational planning process as implemented within DSF have been many: the data collected via our research projects have been instrumental to better inform decision-makers and the public as to the nature of the fishery resources in the state leading to fishery resources having been preserved while expanding or maintaining angler opportunities for the future.

A succinct example of the success of the process was published in the following article in the Fisheries magazine published by the American Fisheries Society:

Bernard, D. R., W. H. Arvey, and R. A. Holmes. 1993. Operational planning: the Dall River and rescue of its sport fishery. Fisheries 18(2):6-13. which expands upon the specifics of the process I’ve described in this current article, and describes an example of the success of the process in saving a fishery from closure.

If you want to learn more about the Division of Sport Fish’s operational planning process please feel free to contact me, Allen Bingham (907-267-2327 or allen.bingham@alaska.gov).

Allen E. Bingham is chief biometrician with the Division of Sport Fish at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He is based in Anchorage.

The author wishes to gratefully acknowledge the guidance and mentorship of my predecessor David Bernard, who was instrumental in the development and implementation of the planning process. The success of the process belongs not only to David, but also the biometricians, the many biologists, technicians, and supervisors involved in implementing the policy both past and present.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.