Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2009

Filling in the Blanks for Susitna Sockeye Salmon

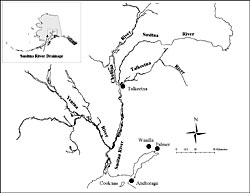

The Susitna River has always contributed a significant share of sockeye salmon to one of the most contentious fisheries in Alaska. Fishery researchers have been trying since statehood to figure out how productive the Susitna River is, in order to manage the fishery in a sustainable manner. But this is a big task, given that the Susitna River drainage area is larger than nine of our states, and the discharge is the fifteenth largest in the U.S. Susitna River sockeye salmon assessments in the past have been aerial surveys for a while here, fish wheels for a while there, weirs somewhere else for another time, and sonar most of all, but that still leaves a lot of blanks.

At the head of Cook Inlet, fed by glaciers, the Susitna River is a tough place to work, with swift currents, numerous shifting channels, and turbid water with zero visibility. After some effort, in 1981 ADF&G settled on sonar at Yentna station as the most practical way to assess the sockeye salmon escapement in the Susitna River drainage each year. Yentna station is located on the Yentna River just above its confluence with the mainstem Susitna. Unfortunately, the sonar is unable to distinguish between Chinook, chum, coho, and pink salmon, which are also common. Fish wheels are necessary to catch and identify fish, to estimate the portion of the sonar count that is sockeye. The mainstem Susitna sockeye remain uncounted, a blank each year. During 1999-2005, the sonar estimates of sockeye at Yentna station were below the escapement goal five of seven years. There were too many blanks in knowledge of Susitna sockeye to be sure of causes and solutions, leading ADF&G to begin a comprehensive assessment of the entire Susitna sockeye run in 2006.

To take on a system the size of the Susitna, it took a combined effort by dozens of technicians, biologists, geneticists, and biometricians to operate two sonars, eight fish wheels, and six weirs. Staff tagged thousands of sockeye salmon, sorted through thousands more looking for tags, conducted hours of radio tracking flights, and maintained eleven radio tracking ground stations. Sport Fish and Commercial Fish Divisions of ADF&G contributed staff and equipment from the Soldotna, Anchorage, and Palmer offices, funded by the State operating budget, a dedicated grant from the Legislature, and Federal Dingell-Johnson grants. Cook Inlet Aquaculture Association, a private nonprofit corporation based in Kenai, joined in with their staff and equipment, funded by a Southeast Sustainable Salmon Fund grant

The sockeye escapement in the entire Susitna drainage was estimated using a mark-recapture method. Fish wheels in the lower river captured sockeye salmon for tagging. Upriver, more fish wheels and weirs captured sockeye salmon to look for the tags. Knowing the number of tags released and the ratio of tagged to untagged sockeye at points upriver allowed calculation of the entire sockeye escapement. The escapement calculated from the mark-recapture method in the Yentna was substantially higher than the sonar-fish wheel method. ADF&G is still looking in to the causes for this and experimenting with improvements. The mark-recapture methods also showed about three-fourths of sockeye were bound for the Yentna River, while the remainder stayed in the mainstem Susitna River.

Radio telemetry allowed researchers to identify the spawning sites for sockeye salmon. Selected sockeye had a radio transmitter, about the size of your thumb, simply pushed down the throat into the stomach. The transmitters emitted a steady stream of radio pulses for at least ninety days. To track tagged fish as they swam upstream, a series of towers throughout the Susitna drainage recorded when a fish passed and relayed the information, via satellite, to a web site. Biologists also spent hours in small airplanes going to the farthest ends of the drainage to locate spawning sockeye, sometimes right up to the faces of some of the many glaciers that feed the Yentna and Susitna rivers. About a third of radio tagged sockeye never went to a lake system, instead dispersing among the many side channels and sloughs throughout the drainage. Weirs, water quality sampling, juvenile salmon surveys, and smolt traps on seven major lakes in the drainage are providing insights into how these systems produce sockeye salmon. Invasive northern pike, which prey on juvenile salmon, have been found in three of the seven major sockeye-producing lakes.

Using advanced genetics techniques, sockeye salmon from major spawning sites in the Susitna drainage had their genetic fingerprint analyzed by the ADF&G Gene Conservation Lab in Anchorage. The known genetic fingerprints were then compared to those from sockeye in the commercial catch throughout Cook Inlet, to estimate the number of Susitna sockeye caught. With better knowledge of catch, escapement, and juvenile sockeye production from major lakes, fishery managers are beginning to fill in the blanks for sustaining Susitna sockeye salmon.

Richard Yanusz is a fishery biologist with the Sport Fish Division. He’s based in Palmer.

Mark Willette is a Soldotna-based fishery biologist with the Division of Commercial Fisheries.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.