Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2009

Tracking Bowhead Whales

Protected from frigid Arctic waters by a foot-thick layer of blubber and built with a powerful sea ice breaking skull, the bowhead whale is perfectly suited to life in the north. Bowheads are mysticetes, like humpback whales – efficient filter feeders and outstanding undersea singers – but unlike humpbacks, they don’t migrate to tropical waters to calve.

Alaska’s bowheads begin to travel north in April, well before the ice has retreated, using leads in the Chukchi Sea and crossing under the ice-covered Beaufort Sea to get to their summer feeding areas near Amundsen Gulf, Canada.

This migration between Subarctic and Arctic waters is profound for Native people of coastal Alaska, who have depended on these whales for thousands of years. Living in communities like Gambell and Savoonga on Saint Lawrence Island, Point Hope, Wainwright, and Barrow, they still hunt and eat bowheads. But they’ve also applied their traditional whaling skills to science.

“They’re the ones that know how to get right on top of whales in small boats,” said Bob Small, the marine mammal coordinator for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “The hunters are the ones who made this a success story.”

It’s a story about whale tracking, using satellites to follow these 60-ton, bus-sized animals across thousands of miles of ocean. This is possible because hunters have equipped more than two dozen whales with satellite transmitters over the past three years. Instead of harpooning a whale to capture it, Native whaling captains have attached transmitters to the whales, allowing them – and everyone else – to follow the whales’ movements on the Internet. A website showing the location of tagged whales is updated weekly.

The project is a collaboration between the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the North Slope Borough, the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and the Whaling Captains’ Associations of the whaling villages, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. The Minerals Management Service funded the five-year study.

Whalers use several methods to deploy the cylindrical transmitter, which implants itself in the whale’s skin upon contact. When the whale surfaces for air, the transmitter sends a signal noting the time and location.

“The art and science of deploying satellite tags is still very much developing,” said Bob Small, who has accompanied the hunters on tagging trips. “Other researchers in other countries are watching this research closely to improve their tagging techniques.”

Researchers need to get close to the whales in small boats. Sometimes the transmitter is put inside a small rocket that is fired from an air gun. The tags and the gun were developed by researchers from the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources who have tagged bowhead whales in Canada and Greenland. The tags deployed last fall were attached to the whales using a long pole. Whalers came up alongside the whales and poked them, sticking the transmitter onto the whale’s back.

“Ideally you want it right off the center of the back,” said Small. “If it’s on center it’s more likely to be damaged by ice. It also needs to be high enough up to clear the water when the whale surfaces.”

The transmitters broadcast for about 10 months. Fifteen whales were tagged in the fall of 2008 near Barrow, and as of April 2009, seven transmitters were still sending signals.

“They are mostly in the Bering Sea now,” said Lori Quakenbush, a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s Marine Mammal Program. “But one whale has been in the Bering Strait area.”

Quakenbush said residents of coastal communities in Northwest Alaska are keeping an eye out for the bowheads, which typically migrate north from the Bering Sea into the Chukchi Sea in the spring.

“They’ll start to see them along the coast any time now,” she said.

Historically, bowheads were found in circumpolar waters of the northern hemisphere, but commercial whalers harvested close to 98 percent of the world’s bowhead population. The tagged whales belong to the western Arctic stock, sometimes called the Bering Sea stock, but five stocks, or geographically distinct segments of the population, are recognized. Over the past decades, the western Arctic stock has been increasing at a respectable rate and now represents perhaps 90 percent of the entire world population and is estimated at 10,500 animals. About 300 young bowheads are born to this growing population each year.

Subsistence whalers have harvested an average of 28 whales annually over the past 30 years. About a dozen Alaska villages harvest whales, with the hunting regulated by the International Whaling Commission and the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission.

“This is definitely a sustainable hunt,” said Small. “Stock assessments show we can continue with subsistence culture and see this endangered population recover.”

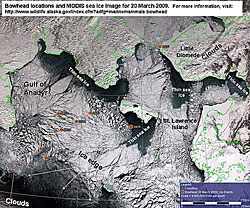

The western Arctic bowheads winter in the Bering Sea. Tagged bowheads mostly spent this past winter in heavy ice along the eastern edge of the Gulf of Anadyr. They move north through the Bering Strait before the pack ice retreats in the early spring, most following leads of open water in the ice through the Chukchi Sea north and east along the Alaska coast to Point Barrow.

Once past Point Barrow they swim east through the ice-covered Beaufort Sea where there is no lead system to follow, headed to Canadian waters. The bowheads spend the summer in the Canadian Beaufort Sea, and in late summer and early fall they migrate back west along the continental shelf. Sometimes they stop at Point Barrow to feed then move west across the Chukchi Sea and down along the Russian coast, passing through the Bering Strait by mid-January.

The tagged whales have been providing specific details about their locations and how long they stay there. In addition, four of the instruments record dive data, which relays the maximum depth of a dive, the time spent at depth and the total duration of the dive. Quakenbush said by comparing this dive data to data recorded during known feeding activity in feeding areas, scientists hope to learn more about what these whales are doing in areas where they linger and as they winter in Bering Sea.

This intersection of traditional knowledge and 21st century technology goes beyond hunting skills. Scientists have interviewed active and retired whaling captains and co-captains, gaining current and historical local knowledge of bowheads movements and behavior near whaling communities. Coastal people continue sharing their expertise as the project progresses, checking the website as it is updated weekly and offering insights into what the whales are up to.

“We get immediate feedback from people about what they see or know relative to what the maps are showing” said Quakenbush. “For example, when we sent a map out in early December that showed all of the tagged whales still north of Bering Strait we heard from several people that St. Lawrence Island was hunting and landed whales in late November letting us know that there were whales well ahead of our tagged whales on the fall migration.”

A major impetus for this study is to learn about migration routes, migration timing, feeding areas, diving behavior, and the time spent in areas within spring and summer range so that the effect of offshore and nearshore oil and gas activities can be better understood and minimized. Such activities may deflect whales away from shore, making hunting more difficult and dangerous. It may also displace whales from feeding areas and may cause oil spills that would affect migrating bowheads.

Small said a variety of scientists are combining the findings of this project with other studies. Some researchers are using instruments to “listen” for whales (acoustic monitoring), and others are sampling what the whales are eating. Oceanographers are looking at seasonal and annual changes in salinity and currents in order to predict when conditions will provide food for bowheads. All of these studies are helping us better understand bowhead whales and their place in the ocean.

Riley Woodford is a writer, editor and producer with the Division of Wildlife Conservation at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.