Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2008

What is This Thing in my Game Meat?

This is the time of year when Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen, Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s wildlife veterinarian, gets frequent inquires from hunters who are concerned about potentially diseased game meat.

If hunters notice something odd or gruesome-looking when butchering an animal, they usually want to know if the meat is safe to eat.

In Fairbanks where Beckmen lives it is enough of an issue that she’s created a flier aptly named, “What is this ‘thing’ in my game meat?”

Fish and Game’s Division of Wildlife Conservation also hands out a 58-page booklet titled “A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in Alaska.” The booklet, replete with gory photos of parasites, worms and diseased organs, might look scary but the bottom line is hunters in Alaska don’t actually have much to worry about.

Most potential problems can be avoided by simply cooking game meat thoroughly, including bones and scraps fed to dogs, Beckmen said.

The most common affliction in Alaska noticed by hunters is tapeworm cysts in the muscles of moose or caribou. The cysts are extremely common – 40 to 70 percent of moose or caribou have some, according to Beckmen – but are so small and usually deep in the muscles they are often go unnoticed.

The cysts aren’t much bigger than a rice grain and are even harder to see once meat is cooked. Beckmen said there is no need to do anything about these cysts because people can’t become infected. But if a hunter wants to take the time, the cysts can be easily picked out by a knife during butchering. If the meat is riddled with tapeworm cysts, Beckmen usually suggests to hunters that they process the meat into burger.

Cooking kills all tapeworms. Typically dogs and other carnivores such as wolves can become infected by eating uncooked meat or animal parts. The tapeworm then grows in the small intestines of the carnivore and lays eggs in tiny packets that are excreted in feces. The packets dry and break open allowing the cycle to continue when herbivores eat plants contaminated with the eggs.

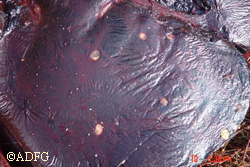

Another common tapeworm is a bit larger and seen on the surface of the liver. The cyst is often called a ‘bladder worm’ because it is a larval tapeworm in a fluid pocket. Like the muscle tape worm, humans can’t get it. Only carnivores eating raw liver can get it. Even though both these tapeworms are common in wildlife, as adults in wolves and as cysts in herbivores, they are not particularly harmful to either animal. If a wolf has a lot of them and is not doing particularly well because of other illness or low prey availability, then the tapeworms can contribute to making the wolf thin, Beckmen noted.

A potentially dangerous form of tapeworm cyst can sometimes be found in the lungs of moose, caribou, deer or other herbivores. The disease caused by these tapeworms is known as cystic hydatid disease. People cannot become infected directly by eating meat infected with the lung tapeworm cysts, but in rare cases, can become infected by coming into contact with dog or wolf feces that contains eggs of the tapeworms.

“It’s only dangerous if it goes through your dog,” Beckmen said.

Should a person contact the disease through handling animal feces, symptoms would take decades to develop and would appear similar to those of liver cancer, Beckmen said. Liver hydatid cysts are not easily diagnosed or treated and are typically removed surgically.

To avoid all parasitic diseases, hunters should cook all meat and animal parts including offal fed to dogs. The lung cysts are much larger than other types of tapeworm cysts – usually about the size of a ping-pong ball up to a small orange – and therefore are easy to find. While they appear hard, they are filled with liquid that will squirt out when the cyst is cut into with a knife or chewed by a wolf, coyote or dog, Beckmen said. That is how the larval tapeworms get into the carnivore’s digestive system, sprayed in the mouth and then swallowed.

Freezing does kill tapeworms but not the most common worm in bear meat, Trichinella, which is a species adapted for life in the cold north. Most of Alaska’s bears are infected, especially farther north but it can also found in wolves, foxes, wolverine, lynx, and walruses.

“Researchers tried freezing polar bear meat for up to six years and still couldn’t kill Trichinella,” Beckmen said.

Trichinosis, the name of the disease when humans are infected, is perhaps the most dangerous disease transmitted through game meat in Alaska. Symptoms of the disease are similar to a bad case of the flu with fever and muscle aches. However, trichinosis is also relatively easy to avoid as the roundworms are killed by thorough cooking.

Beckmen said turning bear meat into jerky is not a safe thing to do. Every year she reminds hunters that jerky meat is smoked but still raw.

“Smoking preserves the meat from rotting but does not kill anything,” she noted.

In addition to those diseases, Beckmen said hunters also commonly ask about abscesses they sometimes find while butchering animals. Abscesses, which are usually caused by an old bacteria-infected wound that becomes walled off and filled with bacteria, are often filled with pus that Beckmen likens to “pistachio pudding.”

If they find an abscess, all hunters need to do is carefully carve around it liberally and throw that part away. After removing the abscess, hunters should carefully clean their knife to avoid contaminating other meat with the pus. If they have a cut on their hand, they also may want to wear gloves to avoid contaminating the cut with pus that may still contain some bacteria.

Beckmen said it is a good idea to cook meat from an animal that had an abscess rather than making jerky out of it – just to be on the safe side.

Information contained in “A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in Alaska” can also be found online at wildlife.alaska.gov.

Elizabeth Manning is an outdoor writer and an educator with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.