Harbor Seal Research

Studies of Harbor Seals on Tugidak Island, Alaska:

Long-term Monitoring Following a Severe Population Decline

The population of harbor seals on Tugidak Island is of particular management concern. Historically, Tugidak was one of the

largest harbor seal haul-outs in the world, with over 20,000 seals. Tugidak saw declines of over 80% in seal numbers in the

1970s and 80s, which resulted in the listing of Alaskan harbor seals as a species of special concern by the Marine Mammal

Commission. During 1995 to 2006, maximum fall counts ranged from 1,523 to 3,333 animals island-wide, and population trends

increased in both the pupping (May – June) and molting (August – September) seasons. Data from harbor seals at Tugidak

Island are available since the 1950s; ADF&G has conducted intensive studies at Tugidak periodically since the 1970s, providing

a uniquely long dataset for a harbor seal population. Declines at Tugidak are also of particular interest due to concurrent

declines observed in other Alaskan pinnipeds, particularly Steller sea lions. Harbor seals at Tugidak may have responded to

presumed changes in carrying capacity in recent decades and therefore, seals may be an indicator of future change, such as ocean

warming. As one of the largest current and historical harbor seal sites in the Gulf of Alaska, Tugidak is a particularly appropriate

representative site for monitoring changes in the Gulf. The ease of observing seals from land also makes Tugidak Island uniquely

ideal for long-term studies.

The population of harbor seals on Tugidak Island is of particular management concern. Historically, Tugidak was one of the

largest harbor seal haul-outs in the world, with over 20,000 seals. Tugidak saw declines of over 80% in seal numbers in the

1970s and 80s, which resulted in the listing of Alaskan harbor seals as a species of special concern by the Marine Mammal

Commission. During 1995 to 2006, maximum fall counts ranged from 1,523 to 3,333 animals island-wide, and population trends

increased in both the pupping (May – June) and molting (August – September) seasons. Data from harbor seals at Tugidak

Island are available since the 1950s; ADF&G has conducted intensive studies at Tugidak periodically since the 1970s, providing

a uniquely long dataset for a harbor seal population. Declines at Tugidak are also of particular interest due to concurrent

declines observed in other Alaskan pinnipeds, particularly Steller sea lions. Harbor seals at Tugidak may have responded to

presumed changes in carrying capacity in recent decades and therefore, seals may be an indicator of future change, such as ocean

warming. As one of the largest current and historical harbor seal sites in the Gulf of Alaska, Tugidak is a particularly appropriate

representative site for monitoring changes in the Gulf. The ease of observing seals from land also makes Tugidak Island uniquely

ideal for long-term studies.

Objectives:

- Monitor long-term population trends at Tugidak through counts of pups and non-pups hauled out during pupping and molting seasons.

- Monitor the timing of pupping and molting annually, as the timing of peak pupping shifted 1–3 weeks earlier in the 1990s, compared to the earlier period of population decline.

Photographic identification and mark-resight techniques

Markings on the pelage (spots and rings) of pacific harbor seals are extensive, unique, and are consistent over at least 10 years.

Natural pelage markings have been used by ADF&G as a means of identifying and following individual harbor seals during large-scale,

systematic photo-identification surveys at Tugidak Island since 1998. Over 30,000 photographs have been collected since the project

began 10 years ago.

Markings on the pelage (spots and rings) of pacific harbor seals are extensive, unique, and are consistent over at least 10 years.

Natural pelage markings have been used by ADF&G as a means of identifying and following individual harbor seals during large-scale,

systematic photo-identification surveys at Tugidak Island since 1998. Over 30,000 photographs have been collected since the project

began 10 years ago.

Use of photo-identification (i.d.) for large populations of harbor seals, such as at Tugidak Island, requires a sophisticated computer-assisted photograph-matching system to ensure accuracy in photo-matching. The first photo taken of a seal “marks” the individual and establishes a photo i.d. for the seal. Each subsequent photo taken of that individual constitutes a “re-sight” of the seal and is used to estimate survival of the individual over time.

Objectives:

- Use photo-identification of individuals and mark-resighting techniques to estimate annual age and/or age-class specific survival probabilities, reproductive rates, pre-weaning pup survival probabilities, population size, annual pup production, and reproductive histories of breeding females.

- Monitor annual and seasonal variation in diet by scat collection.

- Examine how population dynamics (e.g., survival and reproductive success) respond to environmental conditions by combining population, diet and environmental data collected around Kodiak Island, Alaska.

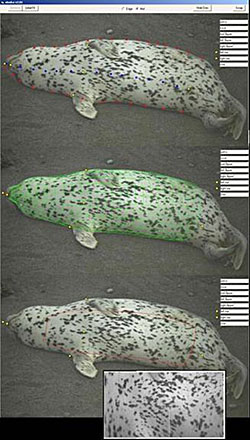

To monitor the seal population on Tugidak Island via mark-resight using photo identification, a novel matching system was developed to

match photos taken of harbor seal ventrums. The system uses a 3-dimensional model of a seal’s body that adjusts for variation in viewpoint

and perspective, and allows extraction of “fingerprints” from two standard regions of the ventrum

(see http://www.conservationresearch.co.uk/).

These fingerprints summarize the pelage pattern as a matrix of grey-scale values, after adjusting for lighting variation in photos. The

system then allows maximum correlations among fingerprints from different photos to be determined and ranks potential matches such that

the most likely matches appear first in the list. Lastly, the system allows a human observer to visually determine matches by eye.

To monitor the seal population on Tugidak Island via mark-resight using photo identification, a novel matching system was developed to

match photos taken of harbor seal ventrums. The system uses a 3-dimensional model of a seal’s body that adjusts for variation in viewpoint

and perspective, and allows extraction of “fingerprints” from two standard regions of the ventrum

(see http://www.conservationresearch.co.uk/).

These fingerprints summarize the pelage pattern as a matrix of grey-scale values, after adjusting for lighting variation in photos. The

system then allows maximum correlations among fingerprints from different photos to be determined and ranks potential matches such that

the most likely matches appear first in the list. Lastly, the system allows a human observer to visually determine matches by eye.

Photos of alternatively marked animals (numbered flipper tags or unique scars from injuries) were collected from 1998 – 2005 and provided an independent test of the accuracy of the photograph matching system. This test demonstrated that matching accuracy and efficiency were very high, with a photograph matching error rate of <0.03 for good-quality photos. This level of accuracy ensured there was negligible bias in survival estimates introduced by the use of pelage markings and photographs to identify individuals. Resighting histories of individuals were created from these photograph-matching results and are being used to estimate life history parameters using mark-recapture models at this important site.

For more information about the Tugidak Island studies, please contact Kelly Hastings at kelly.hastings@alaska.gov.