Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

April 2017

Bats in Alaska

Volunteers needed to monitor bats

On a pleasant evening in mid-May I watched 1,213 bats emerge from a roost in Juneau. A steady stream of one, two, or three bats flew out every few seconds for a half-hour, between 9:45 and 10:15. I know the exact number because a state wildlife biologist carefully counted them.

With the help of almost 150 volunteers in a half-dozen communities across Southeast Alaska, biologists have learned a great deal about Alaska’s bats in the past three years. They’ve documented the presence of species that were not known to be found in Alaska. They’re gaining a better understanding of habitats where bats are found, and their distribution.

Two factors help fuel the current interest in bats – White-nose Syndrome and translocation. White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a fungal disease that infects bats in winter during hibernation. Over the past decade millions of bats in the Eastern US and the Midwest have died from the disease, and it’s spreading. In the spring of 2016, an infected and dying bat was found near Seattle, more than 1,300 miles from the nearest known case of WNS, in the Midwest. How the fungus spread to the Seattle area is unknown, but some biologists suspect the bat hitched a ride on a ship or some other form of transport, and was translocated.

It’s well documented that bats have “stowed away” on boats in North America and been transported to Europe; and to Iceland as well, which has no native bats. Bats in Central America boarded ships passing through the Panama Canal and were discovered en route to Australia. Bats are also translocated when they get closed inside shipping containers. A pallid bat was discovered in Victoria, British Columbia, in a shipment of lettuce from California.

Biologists with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game are working to minimize incidents of “hitchhiking” bats. They encourage people to carefully check camping and boating gear that is pulled out in the spring after being in storage for winter. Bats will tuck themselves away in awnings, umbrellas, covers, and in and among piles of gear, and then get transported in RVs, trailers, and boats.

Biologists also want to know when hitchhiking bats are discovered. This can help biologists better understand, and hopefully combat, the spread of bat diseases to Alaska and other western states. Biologists also want to know if people find sick or dead bats, especially in the spring. More information on reporting sick or dead bats is available at the end of the article.

State wildlife biologist Tory Rhoads is focusing on bats and is organizing surveys in five Southeast communities in 2017 – with the help of volunteers. This is the fourth year citizen scientists have helped with bat monitoring and research.

“The last three years of data have been incredible for us, thanks to citizen scientists,” she said. “Gathering population data on Southeast Alaska bats is crucial in assessing the impact of White-nose Syndrome, should it arrive.”

A great deal has been learned by citizen scientists conducting driving surveys. The process is pretty straightforward: about 45 minutes after sunset, the volunteer drives an established route at 20 mph for about an hour, with a bat detector that signals (and records) when it “hears” a bat. A GPS logs the route and helps record the location of bats. The bat detector translates the high-frequency bat call into something audible to human ears. Rhoads said the citizen scientist can hear the call on the bat detector when it is detected.

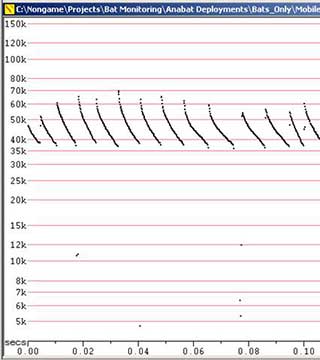

“It’s a kind of repetitive clicking sound,” she said. “The detector also saves a sonogram of the bat call so we can analyze it and determine the species.”

A sonogram is a visual representation of a bird song or bat call, showing the duration and frequency of the sound.

Surveys will be conducted this summer in Juneau, Sitka, Petersburg, Wrangell and Haines. This spring, Rhoads and biologist Steve Lewis will deliver a presentation and training in each community, providing a slide show of the different bat species, results from previous surveys and instructions on how to conduct a survey. They’ll also visit local schools.

Biologists hope to enlist volunteers to drive a survey once a week, or every other week, over a 25-week period between early April and early October. A volunteer can drive a single or multiple surveys.

Patty Kermoian drove surveys the last two summers in Haines, and she’ll be volunteering again in 2017. She drove both the transects in Haines, said setting up the bat detector is fast and pretty easy.

“You’re driving very slow, and you do hear the bat sounds, and sometimes you’ll see a bat,” she said. “There’s a website set up and you can see your results. It’s fun to get the results and find out what bats (species) you’re seeing on the different routes you drive, and how it progresses over the summer.”

There are two transect routes in Juneau, one on Douglas Island and another running from the Mendenhall valley north out the road. There are also two transect routes in Haines, one from Chilkoot Lake to Mud Bay and the other starting at mile 31 on the Haines Hwy and ending downtown. Other communities have a single transect.

The volunteer has flexibility regarding which night to drive.

“It’s totally weather dependent,” Rhoads said. “It can’t be rainy or really windy.”

Volunteers sign a volunteer agreement before checking out the equipment and fill out a data sheet about weather and conditions at the time of the survey.

Bats are active seasonally in Alaska, from April to October, and it’s suspected they hibernate locally. Passive bat detectors set up in Juneau have detected bats in winter.

“Activity falls off at the end of October, but we picked up a silver-haired bat at Auke Lake in December last year,” Rhoads said.

Seven species of bats have been documented in Alaska. The distribution of the most common and widespread species, the little brown bat, includes most forested regions of the state south of the Brooks Range, and in coastal areas extending along Southeast to the Alaska Peninsula and as far north as Norton Sound. Six other species of bat, Keen’s myotis, California myotis, long-legged myotis, Yuma myotis, hoary bat and the silver-haired bat have an annual range that is restricted to Southeast Alaska.

Volunteer for a community driving survey

A two-minute video, “Bat Driving Survey,” shows how the survey process works.

Another video, “Bat Captures in Southeast Alaska,” offers details about bat captures and research in Alaska. Biologists are not planning any bat captures or tagging this year.

More information on citizen science

What to do if you find a sick or dead bat

Bats, bat monitoring, reporting observations, and bat citizen science

Living with Bats: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=livingwithbats.batsinbuildings

Bat species profiles: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=animals.listmammals

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.