Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2023

Southeast Alaska Deer Research

Calling and Capturing deer

The lonesome bleat of a lost fawn carried across the muskeg on a rainy August morning. Almost immediately, a doe popped out of the trees and trotted toward the source, a thicket of shore pine. Crouched within, wildlife biologist Dan Eacker cupped his hand over the deer call and gave another, softer bleat, then raised the capture gun and steadied it on a branch.

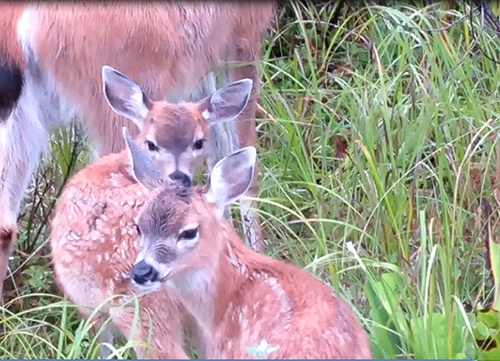

Eacker and his team have darted more than 50 Sitka black-tailed deer over the past four summers on Mitkof Island, near Petersburg in Southeast Alaska, and equipped them with GPS tracking collars. In the week we worked together we encountered scores of deer, many with fawns (deer hunting is bucks only on Mitkof Island, so Eacker favors collaring does). New tools and techniques are revolutionizing biologists’ ability to understand deer in Southeast Alaska, and Eacker is part of this new wave of deer research.

In the Southeast archipelago deer can be abundant, and the hunting season is up to five months long in some areas, with generous bag limits (including does in some places). But conditions vary widely across the region, particularly with regard to predators, weather, and quality of habitat. Some islands have wolves, others don’t - but do have brown bears, or black bears, and the mainland has all three of those predators. Winters vary from severe to mild depending on the year and the location.

As a result, deer populations fluctuate, with dramatic die-offs usually followed by steady recovery during periods of milder winters. To manage the seasons and bag limits, biologists (ideally) would like to know population size, population trends, deer density on the landscape, their movements and how they use their habitat. They want to understand the impacts of a stressful winter with deep, persistent snow, of disease and predation, and over-browsing when numbers are high.

Collars, cameras and DNA

This article looks at capturing and collaring deer, but Eacker’s research has two other major components. He’s swabbing deer fecal pellets in winter, which provide DNA that offers a range of insights. He’s collected close to 800 samples over the past three years, representing about 150 different Mitkof Island deer. He’s also using an array of 88 motion-triggered trail cameras on the island, running year around.

“We have seven primary sites on the island that are either a DNA grid or a camera cluster grid,” he said.

Mitkof is about 10 miles wide and 17 miles long (16 by 28 km) and is the 30th largest Island in the US. Large open, wet muskeg meadows dominate the lower elevations and appear brown. The Stikine River Delta and mainland are on the right, and the narrow channel separating Mitkof Island from Kupreanof Island (left edge) is the Wrangell Narrows. The highway runs south along the narrows and veers southeast along Blind Slough near the center.

The island is about 200 square miles (540 km2) of rainforest, with large areas of wet muskeg meadows. In addition to one stretch of highway, parts of the island have decent logging roads, other areas are difficult to access, especially in winter. The placement of the grids allows him to compare habitat use and deer density in different types of habitat, such as logged versus old growth, and forests under different types of management.

“The trail camera pictures, tracking collar data, and the DNA from deer pellets are working together to provide better estimates of deer numbers,” Eacker said.

Calling and darting deer

Calling can be an effective way to bring a deer into safe darting range. In summer, does can be particularly responsive to a call that evokes the signal of a lost or distressed fawn. Bucks tend to ignore this call and are less likely to be encountered in the field.

Deer are generally pretty quiet, but they produce a variety of sounds, from mooing bleats to coughing barks. Some store-bought deer calls make an estrous call, which hunters use in the rut to call in buck that think a doe is signaling that she is receptive to breeding. Techniques vary from hunter to hunter, some favor loud, repetitive broadcasting, others a subtler approach intended to pique a buck’s curiosity.

Most deer calls use a wide rubber band as a reed. You blow and they bleat. For calling does, Eacker favors the plastic reed from a pet squeaker toy. They have a golf-ball-size plastic bladder attached, and a squeeze generates the squeak. If you cut them out and blow into them, you get a high-pitched wail, a fawn call that does respond to. Sometimes they cautiously peek out from the forest, other times they charge out of the trees and run right in.

“When you call these deer in, there’s a great variation in how they respond to the call,” Eacker said. “Some of them might be going crazy over it. I speculate that’s a lot of does that lost fawns already, they’re ‘Oh! It’s my fawn!’ and they’re going to run up to it.”

He noted that as the summer progresses and the fawns get bigger and more independent, does tend to be less responsive to the call. In a week in August we called in a couple dozen, but not all offered an opportunity to dart. We worked with Tessa Hasbrouck, the Ketchikan assistant area biologist who grew up in Petersburg and knows the area well. She’s also done capture work before.

He noted that as the summer progresses and the fawns get bigger and more independent, does tend to be less responsive to the call. In a week in August we called in a couple dozen, but not all offered an opportunity to dart. We worked with Tessa Hasbrouck, the Ketchikan assistant area biologist who grew up in Petersburg and knows the area well. She’s also done capture work before.

On a few occasions does called back, or answered with a short little grunt. Once a nearby Steller jay squawked a couple times, then to our astonishment delivered a spot-on deer call imitation and flew off.

Darting

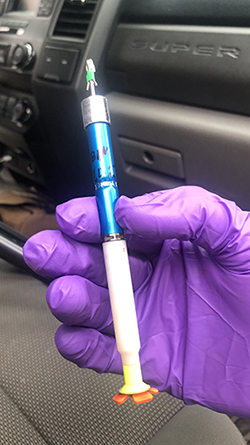

Eacker has found the ideal darting range is about 20 meters. The darting rifle is called a projector and uses a .22 caliber “blank” cartridge to propel the dart.

The dart is a formidable projectile, a metal tube about the size of a Sharpie marker. The front half is loaded with liquid – the drug combination that immobilizes the animal, and it has a small charge that injects the drug on impact. The tail end has a telemetry device that enables a biologist to track and locate the dart, whether it’s attached to a deer that’s run into the woods, or it missed and punched into the muskeg peat moss.

Eacker wants a broadside shot into the rump, and there were times when a fearless doe came in too close. At a dozen meters the dart could have enough force to cause injury, or could actually bounce off. In one encounter, a pair of does approached Hasbrouck and began stomping their hooves – and never provided an opportunity to dart.

Eacker is keenly sensitive to animal welfare and appreciates that this type of capture work is relatively safe for e veryone.

veryone.

“With ground darting, we bring them in close with the call,” he said. “This is not like net gunning out of helicopter, captures that are riskier and more dangerous for the animal and personnel. There is some work where you have to do that, but ground darting is relatively mellow.”

The three-drug combination has a large safety range and is unlikely to cause an overdose. One drug tranquilizes the deer, and the other two relax the animal and smooth out the effects. “The drugs are not lights out,” Eacker said. “They slowly go under, it induces over 10 to 15 minutes. Two of the three drugs in the cocktail are reversable. Ketamine (formerly the preferred drug) wasn’t reversable. Biologists used to sit for hours with the deer waiting for the drugs to wear off. Now a deer is up on its feet in three to five minutes.”

As soon as the dart hits, Eacker checks his watch. On one occasion a yearling doe took a dozen steps after the dart hit, stood still for a couple minutes, then laid down and was soon unconscious. A few days later another yearling ran off in the company of a second animal. Eacker pulled out the telemetry antennae and tracked her for a few hundred yards – she had laid down and the other deer was standing by. The companion stayed nearby throughout the collaring and processing.

Processing and collaring

Once he’s established the drugs have taken effect and deer is safe to handle, animal care is the priority. If there is any concern - if the deer is too hot (above 104) from running, for example, or taking fewer than 10 breaths per minute - Eacker administers the reversal drug right away. Establishing vital rates, getting the collar on quickly and treating the dart wound, are the first orders of business.

Eacker and Hasbrouck gently positioned the deer on a nylon tarp that also serves as a sling for weighing the animal. As ruminants with multiple stomachs and heavy gut, the deer is positioned with the head slightly uphill so pressure is taken off the lungs. A small meter clipped to her tongue provides the blood oxygen level and heart rate, and breathing rate is monitored. A mask covers her eyes and eye lubricant is applied, which protects them and calms the animal. Pure medical oxygen is provided through a tube loosely placed in a nostril.

Eacker trimmed a small patch on her neck and drew blood from her jugular vein. Blood samples are archived and a wide variety of tests can be done as needed. Hasbrouck took a hair sample (the follicles provide DNA), monitored vitals, and prepared the reversal drugs. She flushed the wound and applied a little antiseptic ointment to the dart puncture, but the wound was slight. They measured her, clipped a scale to the sling and gently lifted her a few inches off the ground to get her weight. No ear tag was attached - Eacker doesn’t tag the deer anymore.

“The first year we took a small tissue sample and we put in small ear tags, but we don’t need more samples from Mitkof Island so we don’t do it anymore,” he said. The tissue samples from those first 16 deer provided a good sample of DNA as part of a new genetics project in the region. Biologists are developing a genetic approach that would be able to identify individual deer across their range in Alaska from DNA samples, and tissue provides a high-quality DNA source for constructing these genetic databases.

Eacker had already linked the GPS unit to the satellite the night before, so once the collar was comfortably fitted and fastened Hasbrouck injected the reversal. Designated Deer 48, she was up in a few minutes, a little wobbly on her hooves at first, then rejoined her companion. Deer 48 would prove to be quite mobile in the weeks to come.

Tracking deer movements

These tracking collars today are lighter, last much longer and are more effective than ever before. Location data is also emailed to the researcher.

“These communicate back to the satellite one location per day, and we can track in real time from our desk,” Eacker said. “I could do up to seven locations per day but to save battery power I just do one. The old collars stored the location data on board, and they had to be recovered using only the VHF radio signal. I don’t have to jump in a plane and do telemetry or spend a lot of time recovering the collars.”

The collars are programmed to drop off. The onboard VHF telemetry enables a researcher to locate the collar. That’s still an option, but Eacker said the GPS is now so accurate that in a relatively open forest he can walk right up to the collar. These collars stay on the air for two years.

They also provide a mortality signal; if the animal doesn’t move for a designated period of time (in this case six hours) a signal is sent notifying Eacker. That’s particularly valuable for researchers studying predation and juvenile mortality.

“For a lot of state agencies, these collars are all about learning about animals’ survival,” he said. “Knowing survival is a key demographic parameter. My masters project in Montana was basically ‘What’s eating these elk calves,’ and it turned out to be mountain lions.”

The wolf kill site

“Sometimes you don’t care what killed them, you just want to know if they’re still alive,” he said. “If you do care, you’ve got to get there pretty quickly. The one confirmed wolf kill we had, we got there the next day. There was so much wolf sign – it looked like a bomb went off in there. But what we’ve seen, with 20 to 30 deer on air per year, there is little wolf kill. And the adult females do especially well - and typically have an 85 percent survival rate for ungulates.”

Out of 46 deer collared over the last three years, three died from vehicles, one was wolf-killed, one was harvested by a hunter (a buck) and one died from what appeared to be natural causes.

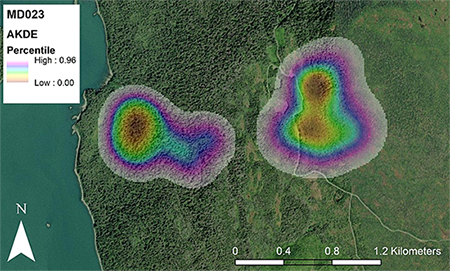

Eacker’s focus with the collars is to link deer density with habitat selection, and to estimate deer abundance. He’s also looking at how much area an animal uses – the size of its home range. He’s getting good preliminary data and will be putting it together with the camera and pellet DNA data.

“The GPS collars provide very good estimates of how much space animals use in different parts of the island,” he said. “In general, the deer keep to a home range of a square kilometer or less, they don’t seem to need a very big area.”

Winter – summer habitats: This image shows the seasonal home range(s) of a Sitka black-tailed deer. She focused on one area in summer at higher elevation (right) and then moved in the fall to a winter range in the old growth forest closer to the shoreline (left). Note that a higher percentile white color represents areas of very little use by the deer while the lower percentile areas (dark brown) were heavily used.

He’s also seeing deer movements.

“Snow has a big effect on deer movement and deer habitat selection,” he said. “In the past people relied heavily on elevation as a predictor of habitat selection. But deer don’t select for elevation specifically.”

Snow can cause deer to make a “facultative movement” – relocate in response to an environmental stressor. “They finally get too much snow and they push down to shoreline,” he said. “One deer moved 14 kilometers in a short period to get out of deep snow and into more favorable forested winter habitat near the beach fringe.”

Another deer left the area the first day of hunting season.

“It was really interesting timing. It crossed Blind Slough and headed to this really remote part of the island where there are no roads. I’ve had a couple deer do that.”

In late September 2023, Eacker saw that Deer 48 had moved close to 20 miles from where she was collared - from Mitkof Island east to the Stikine River Delta on the mainland. This entailed swimming across the strait. “Why did that deer move to the Stikine? I don’t know. Maybe she encountered a pack of wolves, maybe she just dispersed out as a yearling deer. But I would have never caught it if I wasn’t getting this in real time at my desk.”

These videos show researchers and deer in action

Sitka black-tailed deer responds to fawn call

Wildlife biologist calls in deer for darting & collaring

Sitka black-tailed deer with fawns

Riley Woodford has been writing about wildlife research in Alaska and producing Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and the Sounds Wild! radio program since 2003. He can be reached at riley.woodford@alaska.gov

More on Sitka Black-tailed deer

More on Sitka Black-tailed deer

Deer Surveys Offer Insights (2022)

Hunting Black-tailed deer in Alaska, by Mark Stopha

Deer: Southern Southeast is a Different Story

Black-tailed Deer Species Profile

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.