Weathervane Scallop

(Patinopecten caurinus)

Species Profile

Did You Know?

The beauty of scallop shells has long been internationally recognized. Images of scallop shells are used to adorn items such as stamps, family crests, oil company logos, and trail signs along the Camino de Santiago walking pilgrimage in Spain.

General Description

The Alaska scallop fishery harvests the weathervane scallop, also called giant Pacific scallop, scientific name Patinopecten caurinus. Unlike most bivalves (clams and mussels), scallops cannot burrow to escape predation, but instead they detect predators with primitive 'eyes' and have limited ability to swim away by rapid opening and closing of their shells. Scallops require a very large adductor or 'hinge' muscle to maintain this ability. This muscle is what is marketed as a "scallop," although it is only one part of the animal.

Size and sex determination

The biological measurement for scallop size is shell height. This is measured from the base of the hinge to the edge of the scallop shell. Weathervane scallops sexually mature around age 3 or 4 years. They spawn annually during summer and are about 100 millimeters in shell height when they are sexually mature. Sexes can be distinguished by gonad color; female gonads are orange-red to red, and male gonads are creamy white. Otherwise, male and female gonads are similar in size and shape.

Similar species

There are other scallop species in Alaskan waters but none as large as the weathervane scallop. These include: Pacific pink scallop, Chlamys rubida; spiny pink scallop, C. hastata; white scallop, C. albida; arctic pink scallop, C. behringiana; C. islandica; purple-hinged rock scallop, Crassadoma gigantea; Vancouver scallop, Delectopecten vancouverensis; and Alaska glass-scallop, Parvamussium alaskense.

Life History

Growth and Reproduction

Scallops are dioecious (have two sexes), broadcast spawners that reproduce by assembling and releasing clouds of gametes (eggs and sperm) which are fertilized in the water column. The signal for scallop spawning is thought to be increasing water temperature, which occurs in May and June in Alaska. Fertilized eggs settle to the bottom where they develop after a few days into a tiny transparent-shelled veliger larvae. Veliger larvae swim in the water column and feed on microplankton (small free-floating plants) for a period of about three weeks before settling to the bottom to begin life as a benthic (bottom-dwelling) filter feeder.

Weathervane scallops begin to reproduce at three or four years of age at a shell height of about three inches and become commercially harvestable at about four inches shell height and age four to six years. Scallops reach a maximum age of approximately 28 years in Alaska. Like other bivalve mollusks, scallops are aged by counting the rings on their shell which are formed by alternating periods of slow and fast growth associated with seasonal changes in temperature and food availability. The two valves of scallop shells are not identical; scallops lie on the rounder bottom valve, while the top valve is relatively flat.

Range and Habitat

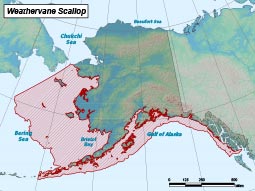

Weathervane scallops are distributed from California to the Bering Sea and as far west as the Aleutian Islands. Scallop beds in Alaska are located on mud, sand or gravel substrate in depths of 120 to 390 feet. Adult scallops assemble in dense "beds" with a characteristic oblong shape that parallels the direction of the prevailing current.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Status

Commercial fisheries for weathervane scallops in Alaska are currently prosecuted from Cape Spencer in Southeast Alaska to north of Unimak Island in the Bering Sea.

Trends

Historical harvest of weathervane scallops in Alaskan waters peaked at 1.85 million pounds of shucked scallop meats in the 1969/70 season. The long-term average harvest for 1993/94–2013/14 seasons is 601,901 pounds. . The federal overfishing level developed in 2012 is 1.29 million pounds of shucked scallop meats and the annual catch limit is 1.161 million pounds.

Threats

Primary threats to this species include habitat damage, ocean acidification, disease, and predation by crabs, seas stars and octopus.