Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2020

Counting Caribou

New video documents wildlife management

Knowing that thousands of caribou inhabit northern Alaska is one thing - but seeing them blanket the tundra is another.

“I think a lot of people are kind of in disbelief that you can go out in one day or a few hours and see and photograph hundreds of thousands of caribou like we do,” said caribou research biologist Lincoln Parrett. “It can be hard to wrap your head around, but they are out there, and they get into these big groups. It may only happen one or two days a year, so we have to be on the ball when it happens.”

Photographing those animals - the photocensus - is an important part of managing caribou in Alaska. In recent years GPS technology and digital color photography improved the process, but counting caribou is a remarkable effort – coordinating crews and aircraft in remote areas, unpredictable weather making or breaking a survey, and caribou suddenly deciding to move hundreds of miles across the landscape.

“We are very dependent on all these factors coming together,” said Heather Jameson, an education outreach specialist for Northwest and Western Alaska (Region 5) based in Nome. Region 5 staff and caribou biologists have long wanted to document the photocensus and share the scale of the caribou herds.

“The census is all these moving pieces,” Jameson said. “We knew the story we wanted to tell, but how do we convey the many moving pieces that have to come together? Even up to the day it’s supposed to happen you don’t know if it can, and some years it doesn’t.”

In 2018 Jameson and her colleagues began capturing video footage and pictures to make a documentary on the photocensus.

“There’s no way you can verbally explain this to people and have them really get it; you have to see this stuff,” said Mike Taras, Jameson’s counterpart in Fairbanks for Interior and Northeast Alaska (Region 3).

Jameson and Taras were part of the steering committee planning the video. “We had outreach specialists – our education staff, and content specialists – biologists, all working together to plan the shots to take,” she said.

In September 2020, Fish and Game released Counting Caribou, providing a birds-eye view of caribou and an inside look at caribou research.

Alaska's Caribou

Caribou move across vast reaches of expansive open country. In Alaska, 32 herds are defined by key areas of their range and the calving grounds where they gather seasonally. Herds vary in size, from the wide-ranging Western Arctic and Porcupine herds that number in the hundreds of thousands, to smaller herds numbering in hundreds or low thousands.

Caribou herds shrink and grow, influenced by weather, disease, population dynamics and predation. Monitoring those fluctuations is a key aspect of managing caribou hunting and harvest in Alaska. At least 22,000 caribou are harvested annually for food, and about 97 percent of that harvest is by Alaskans.

Caribou congregate in summer for breeding and calving. Summer also brings bot flies, mosquitos, and warble flies - blood-sucking, biting and parasitic antagonists that drive caribou to pockets of refuge. Those caribou, concentrated in tight bunches on snowfields and windy ridges, are conducive to aerial surveys and aerial photography.

Starting in the 1970s, large format black and white aerial photographs were taken of the larger herds so animals could be systematically counted. Department caribou biologists, seeing these large aggregations of caribou, realized they could take advantage of that behavior. As radio collars came into use and became more prevalent, finding all the radiocollars in a small area made it apparent that they were probably seeing most of a given herd when the conditions were right.

The photocensus technique is particularly valuable for monitoring the seven largest herds: the four large artic herds – The Western Arctic, Central Arctic, Teshekpuk and Porcupine herds, and the three large Interior herds – the Fortymile, Mulchatna and Nelchina herds. Herds tend to be surveyed every two to four years, if possible.

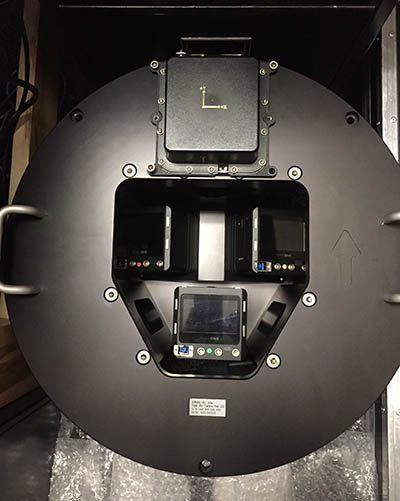

The department’s camera-equipped de Havilland Beaver, a high-wing, short take-off and landing bush plane, has long been a key asset to the surveys. A smaller plane, a Cessna 206 is also camera equipped.

Photocensus coordinator Nate Pamperin helped with the script and reviewing the video, and he is also interviewed on camera. Since he joined in 2011, he has planned and participated in dozens of surveys and helped with the transition from black and white photography to the digital system.

“We knew we needed to go digital, but it was a long process, researching, getting funding, and getting the system built,” he said. “What we do with the system is different from what other people do with aerial photography.”

The transition required more than just a couple new cameras mounted into the belly of airplanes. The system interfaces with GPS and software that makes sense of the process and the products.

It’s a fairly straightforward matter to plan and execute aerial photography of city or agricultural land, Pamperin said. Caribou herds are trickier. “We don’t know exactly where the pictures will be taken until we see the group,” he said. The software written for the old system wasn’t a good fit for the new, more accurate GPS system, which covers a much larger ground swath than the film camera, requiring fewer transects.

The video conveys that well, thanks to animation. “When the idea first came out about doing the video, I had been doing a bunch of research on camera systems,” Pamperin said. “I’d come across an African elephant census, and I’d been looking at their website and saw an animation of the plane flying over the elephants. I suggested that animation would be the best way to depict this, and Mike worked with an animator. He’d get a rough cut and send it to me, and we went back and forth to make it clear to people.”

Biologists photograph caribou with digital SLR cameras in addition to the large format cameras, providing good still images for the documentary as well as the surveys. Taras captured some of the footage as he helped with the surveys, recording data. Some footage in the cramped interior of the aircraft was recorded on cell phones, “while trying to hold a clip board and do your job,” he said.

GoPro cameras proved useful; Jameson put GoPros on a couple of the survey and spotter planes, and a GoPro 360 on the Beaver.

In addition to capturing caribou and the survey crews at work, footage of landscape and wildlife was needed to help set the stage – known as B-roll. “We knew we needed a shot of mosquitos, and weather rolling in, to convey inclement weather,” Jameson said.

“Last year we did the Western Arctic Herd census, and Heather had a camera out there and captured footage,” Taras said. “Other people contributed short clips that were really important, like putting collars on caribou. That helps a lot.”

Part of the story is what happens after the herd is photographed. “People knew we went out and tracked caribou, but people didn’t realize what goes on between taking the pictures and releasing the numbers,” Pamperin said. Counting caribou on digital photographs has advantages over the old black and white pictures, but technology does not provide any magic bullets.

“There is software that can detect these things – caribou in the pictures, but a lot of what is commercially available doesn’t really do what we need it to do,” Pamperin said. “Technology can help – hopefully save some time – but people have to do quality control. A human can interpret the pictures, a person can see a calf under a mother because there’s an extra leg showing. It’s easy to see caribou against uniform green tundra but it’s really hard against similar colored backgrounds like talus or rocks, or grey colored gravel.”

The video offers insights into that process, and Lincoln Parrett highlights the role of statistics in fine-tuning the population estimates.

One science teacher is already developing a biology curriculum based on the census and the video. Russell Shurtleff, a hunter and a biology teacher at East High School in Anchorage, said teachers are working hard to find engaging, active learning tools that can be delivered via distance education.

He and his wife both harvested Nelchina caribou this year, and he wrote, “I had a Zoom class from my garage where the students got to observe the meat hanging, and immediately I saw they were engaged and curious. This made me reassess how I plan on teaching the scientific method … I began modifying a lab I used to do in class counting a population of skittles to something that would be more visually interesting.”

Counting caribou proved to be more interesting than counting skittles.

Wildlife for the Future - one of the volumes from the Alaska Wildlife Curriculum. It is geared for middle and high school students and there are several lessons related to population dynamics. There are also a few case studies to draw from.

Wildlife educators and biologists published Caribou Trails and other outreach publications over the past decades to provide insights and updates on caribou, including the Western Arctic, Central Arctic and Fortymile herds.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.