Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2020

A new field guide for moose health in Alaska

Fall is a greatly anticipated time of the year in Alaska for many reasons, and moose hunting season is one of them. The fall season is also a busy time for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) Wildlife Health Program, as an influx of hunters in the field means more people out observing and interacting with wildlife. As a result, the ADF&G Wildlife Health Program receives a lot of calls and questions about moose flies, tapeworm cysts, and other common moose conditions.

To help address common questions and streamline reporting procedures, ADF&G created a new field guide that describes common moose diseases and parasites. The main objectives of the guide are to help hunters identify conditions they may observe in moose in the field and learn about steps to take for the safety of humans or pets. The guide also lists what samples and reports are requested from the Wildlife Health Program.

The guide is divided into types of conditions: external conditions, internal conditions, conditions that are not easily visible, human-caused conditions, and finally some diseases that ADF&G is watching out for that have not yet been detected in Alaska. For each condition, there are identical subsections that include a description, a list of the signs to look for, safety information for people and pets, prevention (i.e. how to keep a parasite from spreading or what to do to avoid any contamination of meat), and how to report or sample conditions that ADF&G might be seeking information about.

When asked what she wants people to know about moose diseases and parasites, ADF&G Wildlife Health Veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen says many parasites, bacteria and viruses are part of the normal internal biology of wildlife, and she stresses that she almost never sees a moose without any parasites such as tapeworm cysts – and that most do little harm to the moose or the safety of harvested moose meat. Moose in poor health can have unusually high numbers of parasites and/or complicating factors that led to an actual disease from “normal” parasites or bacteria.

Some abnormalities, diseases or parasites are easily seen on the skin, hooves, or antlers of moose in the field, often from a distance. Dr. Beckmen says one of the most common external conditions that she hears about or sees in the lab include papillomas (or warts). These occur most commonly on the chest, head, or legs of moose. The other external condition ADF&G gets a lot of questions about is the bites of moose flies, which attach onto the hind thighs of moose during the summer, but generally drop off in fall and do not usually have a lasting negative effect.

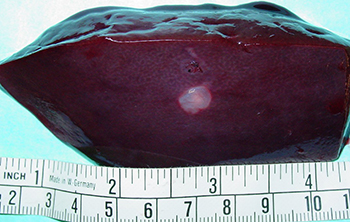

ADF&G receives the highest number of calls about internal conditions found during meat processing. Most commonly, about cysts in the muscle, heart, and lungs made by tapeworms; and almost as often about abscesses, or soft swellings containing pus usually caused by wounds, that become walled off in a capsule. Tapeworm cysts and abscesses are very common, and moose meat with them or other internal conditions can generally be consumed safely with some basic guidelines: cut around infections, remove any contaminated sections, and cook meat thoroughly. Each condition listed in the guide has more specific information about what to look for and what may warrant extra precautions, to help hunters feel more confident in how to safely process and consume any moose they harvest.

The guide also describes observable signs for some parasites that are microscopic and not easily visible. In addition, there is a section describing some common conditions caused by the interactions between people, pets, and moose. For instance, some plant species that people use in home landscaping can sicken or kill a moose, which a lot of people do not realize are harmful – Japanese yew, and bird cherry/chokecherry bushes, for example.

Finally, the guide mentions pathogens that the Wildlife Health Program is watching for that are most likely to be introduced to Alaska by moose, elk or deer crossing the border from Canada (for more information about range expansions of mule and white-tailed deer and harvest regulations, (see the Alaska Fish and Wildlife News article from July 2019). Beckmen asks hunters and outdoor enthusiasts to watch for the characteristic triangular pattern of hair loss across the chest, shoulders and back that may indicate winter moose tick, specifically between the months of October and March - moose have other sources of broken hairs or hair damage in later spring and summer - especially if you live and hunt near the Canadian border.

Pick up a copy of the guide in any local ADF&G office or find it online here – Moose Health and Disease: A Pocket Guide – to save and view it on any mobile device. ADF&G appreciates all the people out in the field each year that help keep an eye on wildlife health and that are willing to call, email, or submit samples – one objective of this guide is to make it easier to know what ADF&G is monitoring and the reports that are most helpful. You can find many other resources on the ADF&G wildlife parasites and diseases main page such as sample submission forms and wildlife health news. Check this website often – we are working on updating the library of disease and parasite pages, and a complementary caribou health guide is due out later this fall.

Jen Curl works for ADF&G in the Fairbanks office in the Division of Wildlife Conservation and as part of the Wildlife Education and Outreach program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.