Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

September 2020

Salmon shark tagging in the Bering Sea

Who knew that the great white shark’s smaller cousin routinely makes its home in Alaskan waters? We’re talking about the salmon shark (Lamna ditropis). The salmon shark ranges from the Bering Sea to the Sea of Japan and from the Gulf of Alaska south to Baja California. Believed to be the most endothermic of the lamnid sharks, which includes the great white, makos, and porbeagle sharks, salmon sharks can maintain their internal body temperature up to 21°C above ambient water temperatures. Given their ability to withstand cold ambient temperatures, salmon sharks may be one of the more northern dwelling sharks in the world and have been caught as far as 67°N – above the Arctic Circle.

Like other sharks, salmon sharks segregate by sex. Female salmon sharks dominate the eastern North Pacific while male salmon sharks dominate the western North Pacific, inclusive of the Bering Sea. Salmon sharks are commonly found feasting on salmon in Prince William Sound in the summer months and those sharks, most of which are female, have been satellite-tagged and tracked extensively (Fish and Game researchers Lee Hulbert and retired biologist Kenneth Goldman contributed to this work in the past). However, salmon sharks have not been satellite-tagged in the Bering Sea (spoiler alert: they have now!). Additionally, in line with what we know about sexual segregation in salmon sharks, most of the salmon sharks encountered in the Bering Sea are male which provides a unique opportunity to spy on a portion of the salmon shark population that has not yet been thoroughly studied.

Salmon sharks are incidentally caught during the Northern Bering Sea Surface Trawl Survey which primarily focuses on juvenile salmon #NBSsurvey. A trawl is a conical shaped net that is pulled through the water and funnels fish into the back of the net. A surface trawl uses buoys and floats to keep the top of the net near the surface in order to sample fish in the upper portion of the water column. The net used for the Northern Bering Sea survey typically fishes the upper 20 m of the water column. Typically, one or two salmon sharks are caught annually during the Northern Bering Sea survey.

Tagging sharks

The primary objective of this project is to attach satellite transmitters to any salmon sharks caught during the Northern Bering Sea trawl surveys to assess movement patterns and how they relate to variables like season and prey availability. We are specifically interested in western North Pacific sharks because they haven’t been tracked with satellite transmitters before (a Japanese tagging study in the 1980’s used conventional tags which require sharks to be recaptured to find out how far they moved between the point of tagging and the point of recapture). Currently, the stock structure of salmon sharks in the Pacific Ocean is unknown and tagging data will allow us to determine if Bering Sea salmon sharks migrate south to Japan (mirroring the Alaska to California migration of the eastern North Pacific salmon sharks) or if western North Pacific sharks migrate to the eastern North Pacific and comprise a single stock in the North Pacific.

Two different tags are used for this project. One tag, called a SPOT (Smart Position and Temperature transmitting tags, Wildlife Computers), transmits the shark’s daily location when it is finning at the surface. The SPOT tag is mounted to the dorsal fin of the shark and has wet/dry sensors that indicate when the tag is at the surface and should transmit a location. The second tag, called a PSAT (pop-up satellite archival tag, Wildlife Computers and Microwave Telemetry), collects and archives data on depth, light, and temperature and pops-off on a scheduled date, floats to the surface, and transmits archived data via satellite to a computer. The PSAT is attached to the musculature in the shark’s back using stainless steel dart tethers.

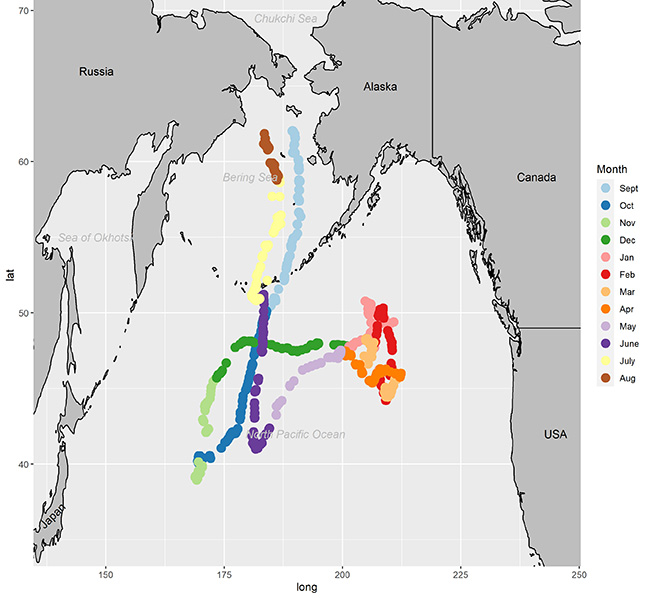

Two male salmon sharks have been tagged as part of this opportunistic effort. The first male was tagged in 2017 with a PSAT near St. Lawrence Island in the Northern Bering Sea. That male shark carried his tag for 12 months while the tag collected its data. The tag successfully popped-off in September 2018 and provided the longest known track for a male salmon shark (the previous record was 26 days by a shark tagged in Prince William Sound). Light level data collected from the tag allowed us to reconstruct the shark’s daily position using local sunrise and sunset times coupled with sea surface temperature data.

A shark's journey

A second male salmon shark was tagged just south of St. Lawrence Island in September 2019. The 2019 male salmon shark was equipped with both a SPOT tag and a PSAT. Double-tagging the shark allows us to collect high-quality location information from the SPOT tag in addition to depth and temperature data from the archival tag. Furthermore, we can use the high-quality location data from the SPOT tag to verify the location data derived from the light level readings of the PSAT. The 2019 salmon shark has been transmitting daily locations since he was tagged. To date, he has traveled from the Bering Sea to the Emperor Seamount, east to the Gulf of Alaska, and back to the Bering Sea. The SPOT tag should have enough battery to provide another two years of location data and we are excited to see how his migrations look from year to year. The 2019 PSAT is scheduled to pop-off in early September 2020.

We have more tags in stock and are hoping to deploy them on sharks caught during future surveys. Although we have only deployed two tags to date, the two male sharks of similar size tagged in the Northern Bering Sea had completely different tracks. There is so much to learn about this iconic Alaskan predator.

This project is a collaboration with and would not be possible without: Sabrina Garcia (ADF&G), Cindy Tribuzio (NOAA), Andrew Seitz (UAF), Michael Courtney (UAF), Julie Nielsen (Kingfisher Consultants), and Dion Oxman (ADF&G).

To keep tabs on our salmon shark’s journey over the next few years, keep coming back to ADF&G - The Undersea World of Salmon and Sharks page for updates and more information! ADF&G - THE UNDERSEA WORLD OF SALMON AND SHARKS

To keep tabs on our salmon shark’s journey over the next few years, keep coming back to ADF&G - The Undersea World of Salmon and Sharks page for updates and more information! ADF&G - THE UNDERSEA WORLD OF SALMON AND SHARKS

Sabrina Garcia is a marine research biologist for Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game based in Anchorage. In the summer, she can be found on ships in the Bering Sea studying the early marine ecology (abundance, distribution, and diet) of juvenile salmon.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.