Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2020

Fish and Wildlife Management in the United States

Article 2: Today’s Management Model

Have you purchased your 2020 fishing or hunting license yet? What are you waiting for? Your purchase of a fishing or hunting license creates amazing power for management, monitoring, and research of your fish and wildlife resources.

Those of you that are regular readers of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News (AFWN) may remember the introduction in January (see ‘Reflecting on Our Shared Resources a Historical Perspective on Wildlife Management’) of a four-part series exploring the unique approach to fish and wildlife conservation in the United States. This month we continue that exploration by diving into the current mechanisms in place to safeguard and manage fish and wildlife in this country and Alaska. You may remember the historical perspective from which our country’s fish and wildlife management policies arose and why many of those policies were formulated around fishing, hunting, and trapping (e.g. consumptive uses). The Public Trust Doctrine (PTD) was also introduced, the notion that all fish and wildlife are held in trust for the benefit of all citizens.

This article will further delineate the role of the PTD and how that dictates everything state and federal fish and wildlife management agencies try to accomplish as trustees and trust managers on your behalf. But first, did you buy your fishing and hunting license yet? I’m not kidding!

Funding Conservation

In the first article I wrote about the primary funding sources for state fish and wildlife management agencies like the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). Pittman-Robertson (PR) and Dingell-Johnson (DJ) funds are collected from excise taxes on firearms and ammunition (PR) and fishing rods, lures, and marine fuel (DJ). Those funds are distributed to each state on an equitable basis assuming each state has sufficient match (e.g. fishing and hunting license revenue). For every $1 of state revenue (e.g. licenses) a state can collect $3 federal PR or DJ dollars (based on land area and licensed hunter/fisher population). These funds support fish and wildlife research and monitoring, hunter education programs, and angler and hunter access projects through your states management agency. Absalom Robertson (co-sponsor of the PR bill signed in 1937) only agreed to sign the bill if it stated the funds would never be diverted to other purposes than administration of state fish and game departments. That is why the PR and DJ funds remain the financial backbone of state fish and wildlife management agencies 80 years later. This “user-pay, public benefit” system has become what many of us have taken for granted regarding the stewardship of our fish and wildlife resources.

According to the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, $797 million was generated by the PR Fund and $632 million by the DJ Fund last year alone. Nationally, last year states generated $872 million in hunting license revenue and $724 in fishing license revenue to match those federal PR and DJ funds. Since 1939, state fish and wildlife management agencies have received over $62 billion from fishers, hunters, and trappers.

In Alaska, as the Administrative Operations Manager for the Division of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) within ADF&G, Greg Williams has a unique perspective on the value of PR funds. “The majority (90 percent) of the DWC’s budget is from hunting license revenue and federal PR match,” he told me. “Over the last four years we are right around $30 million of PR for our annual federal apportionment and this does not include State of Alaska hunting license sale revenue. Our hunting license sales provide the majority of the match for those PR dollars.” The DWC and Division of Sport Fish (that matches fishing license revenue with DJ funds) do receive state general funds but it is a very small percentage compared to other state agencies.

However, PR and DJ funds do not support state game wardens or the enforcement of state fish and game laws. The law enforcement side of fish and wildlife management (Alaska Fish and Wildlife Troopers) is funded through state general funds or state hunting and fishing license revenue (in most other western states) and not federal PR or DJ funds. The reason for this is to avoid federalizing law enforcement activities that are wholly state-based in policy. Therefore, the health and status of our fish and game law enforcement is largely based on either the health of each state’s economy or the number of hunting and fishing licenses sold.

Public Trust

You might wonder how, if it’s a public resource, does that money benefit you as a fisher, hunter, trapper, birder, or general outdoor enthusiast? In order to answer that question we must first take a step back to understand the PTD, the very foundation of all fish and wildlife management policy in this country.

The PTD is considered the cornerstone of modern fish and wildlife management in this country. It states that certain natural resources, water, fish, and wildlife are held in trust by the government (typically the states) for all citizens (beneficiaries of the trust). Each state acts as trustees much like a company’s 401k investment manager on behalf of its employees. When it comes to fish and wildlife the trustees are generally each state Legislature. They delegate their authority either to the regulatory bodies responsible for making regulatory and resource allocation decisions (as in Alaska) or the state fish and wildlife agency commissioner. These regulatory bodies consist of members generally appointed by the governor. In Alaska, The Board of Fish (BOF) and Board of Game (BOG) are each seven-member, governor appointed bodies that are responsible for making allocative and regulatory decisions about our state managed fish and wildlife populations (the next article in this series will deal specifically with Alaska’s BOF and BOG processes). The trust managers are often the agency directors or commissioner (as in Alaska). In Alaska, the Legislature has designated separate authority to the commissioner versus the BOF or BOG. This allows the BOF or BOG to speak on behalf of the beneficiaries (you) and the Commissioner to speak on behalf of the resource. Biologists work on behalf of the commissioner and the resource and are not tasked with making decisions or recommending particular action, that’s the job of the BOF, BOG, and you and other members of the public. Biologists simply collect as much unbiased, objective, scientifically-defensible information as possible to inform decisions by the BOF and BOG (trustees) which have fiduciary responsibilities for the long-term welfare of the resource. You, as the beneficiary of the trust, are tasked with engaging and providing recommendations to the BOF and BOG regarding the stewardship of your resource. Buy a license, attend a board meeting, and engage in the management of your resources.

In Alaska, the state constitution specifically addresses the sustainable use of fish, wildlife, water, and environments for all citizens. It states that the resources will be utilized, developed, and maintained on the sustained yield principle, subject to preferences among beneficial users. Not all states specifically address fish and wildlife resources in their constitution. Alaska clearly takes the use and sustainable management of these resources seriously.

How Funds are Utilized

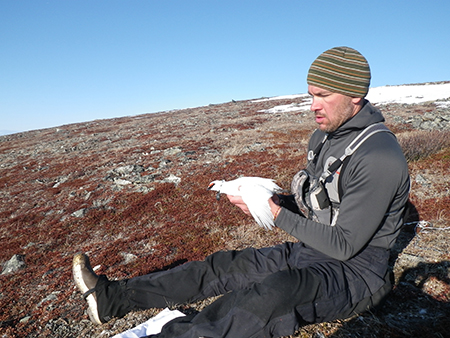

So back to our earlier question: what do biologists do? How is all that fishing and hunting license money spent anyway? Once matched with state license revenue, PR and DJ funds come into each state to support the trust managers (biologists) in their endeavor to pursue objective, scientifically-defensible research, population and harvest monitoring, and public engagement. For example, in Alaska, monitoring one specific moose population is incredibly expensive. To generate a robust, defensible, unbiased population estimate may require weeks for four to six biologists, four to five aircraft, aviation fuel, and logistical support. This may require $30,000-$50,000 for one complete survey of one moose population (and there are many in Alaska). All of the research and monitoring completed by dedicated biologists at each state fish and wildlife management agency is for the sole purpose of informing the trustees (BOF and BOG) as they and they alone have the responsibility of making decisions in the best interest of you, the beneficiary.

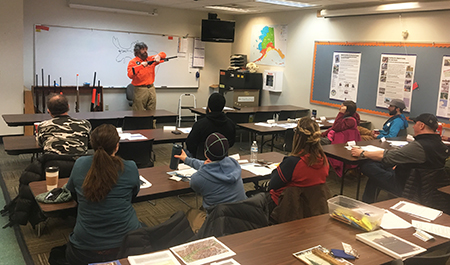

Those funds also educate new and young hunters through statewide hunter education programs administered largely by volunteer instructors across the state. PR and DJ funds support backcountry access and public easement projects to improve access to these resources. They support fish hatcheries, stocking programs, shooting ranges, and boat launches.

Alaska’s Unique Dual Management

States take the lead role across this country in managing resident fish and wildlife resources. However, Alaska has become unique since 1990 when the USF&WS and ADF&G created dual management structures for subsistence users. Article 8 in the Alaska State Constitution provides a subsistence fishing and hunting opportunity for all residents. However, in 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was created that provided among other things, Title 8 - a rural preference for subsistence use in Alaska. The State of Alaska made attempts to comply and modify its constitution with a rural preference provision but was found in violation of the equal access provision under the state constitution that stated all residents (rural and urban) can take advantage of subsistence opportunities. Therefore, after years of legal wrangling the USF&WS took over subsistence management on federal lands in Alaska. Currently the ADF&G and USF&WS work closely with regard to monitoring populations, conducting joint research, and regulating season and harvest limits.

As mentioned in the previous article, various federal agencies do manage other species that cross state or international borders (eg. waterfowl) or marine mammals or have national policy implications (endangered species). Various agencies also manage parcels of federal land for recreation and timber harvest (U.S. Forest Service), preservation (National Park Service), and fish and wildlife refuges (USF&WS) just to name a few.

Valuable NGOs

It’s important to recognize the value of non-governmental organization (NGOs) contributions to our shared resources and the habitats in which they’re found. There are innumerable NGOs with varying scales and goals. There are many conservation organizations like Safari Club International, Ducks Unlimited, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Boone and Crockett Club, Trout Unlimited, and the Ruffed Grouse Society to name just a few. These organizations offer a broader platform for engaged, passionate outdoor enthusiasts and sportsmen and woman to voice their views on land and water use policies, hunting and fishing regulations, fish and wildlife population monitoring and research, habitat protections, and recruitment and retention of fishers, hunters, and trappers. There are many land and habitat protection organizations like the Nature Conservancy, the Audubon Society, and 4Ocean. These groups also engage passionate members to support land and water quality policy and projects on the landscape. Often forgotten are the numerous and large contributions by corporations or other private entities to support access projects, community outreach, and fish and wildlife research. Through all of these avenues, hundreds of millions of dollars are raised annually for the collective benefit to our local communities and fish and wildlife resources. These organizations often function in concert with both state and federal land and resource managers who help inform decisions and make the most effective use of financial resources.

All of these mechanisms together create one of the most envied and emulated resource management structures in the world. We are extremely lucky that as residents of this great country we had forbearers with tremendous forethought and insight regarding resource policies, protection, and funding that has truly withstood the test of time. As current stewards and beneficiaries of these great resources it is our responsibility to make sure we don’t lose ground and that we also look to the future to manage and safeguard these resources for our great grandkids. The greatest risk to our resources is not funding, staff, or facilities; it’s apathy, ignorance, and disengagement.

These are not only your resources but more importantly those of your grandkids and their kids. They too are beneficiaries of this trust and we must do our part to engage the processes at play to affect positive change for the future. The next article (#3) in this four-part series will address just those avenues through which you can affect change here in Alaska. There are many ways and levels through which you can engage and have your voice heard.

Stay tuned, and don’t forget to buy your 2020 hunting, fishing, or trapping license!

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.