Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

June 2019

Submit a tick!

My 9-year-old daughter returned unhappy from an outdoor birthday party in a Juneau city park in early June. An adult friend had noticed a tick crawling on my daughter’s shoulder and picked it off to show people. Ticks are pretty unusual in Juneau, and our friend Kerry wanted folks to see what they look like. My daughter was embarrassed, and I explained there is no shame in someone spotting a tick, but more importantly, what happened to the tick?

Kerry squashed it, she said. Too bad she didn’t know that Alaska researchers are collecting ticks. She should have dropped it in a small container and brought it to a local Fish and Game office, or sent it in to the state veterinarian.

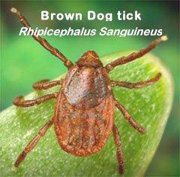

Researchers in Alaska are monitoring the state’s native tick species, and the more recent introductions of non-native ticks - as well as tick-borne diseases such as tularemia. This year, the project includes some active searches for ticks.

The study is a collaborative effort between the University of Alaska (Anchorage, Fairbanks and Southeast), Fish and Game, and the Office of the State Veterinarian. UAA Professor of Environmental Health, Micah Hahn, leads the project, which includes setting up field sites in several parks in Anchorage and the Kenai Peninsula to look for ticks on wildlife. ADF&G veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen works with Fish and Game biologists to collect any ticks that might be found on wildlife that are captured during research and management projects. UAF professor of veterinary pathology, Dr. Molly Murphy, will test the ticks for pathogens that can carry diseases such as tularemia, Babesiosis, and Lyme disease.

Bob Gerlach, the state veterinarian, is the contact for ticks found on people, pets and domestic animals. Although ticks go to either Gerlach in Anchorage or Beckmen in Fairbanks, the same sample submission information is needed, the packaging method is the same and all the ticks eventually end up in the study.

“This is a cooperative effort,” Beckmen said. “We need the public and we want them to participate, but we need the efforts to be rewarded with information that is scientifically useful.”

The number of human cases of tick-borne disease in the United States has tripled over the past two decades, and the geographic range of many tick species has expanded substantially due to changes in climate, land use, and human and animal movement.

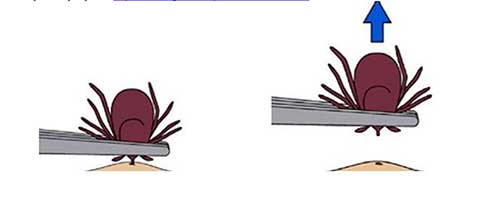

If you find a tick on your pet, you can remove it yourself or take your pet to a veterinarian. It’s easy to remove a tick. You don’t need to torture ticks with oils, solvents or heat (heat causes the tick to regurgitate material back into the wound and should be avoided). Use fine pointed tweezers, grasp the tick close to the skin, apply firm, steady tension straight out and in just a few seconds, it will release. Don’t squash it. Any fluids released are infective too so you don’t want to get any of the fluid in a cut or on your skin. Wash the wound and your hands afterward.

Put the tick in a small unbreakable container. It is best if it is in a small amount of ethanol (vodka works in a pinch if we know that is what you used) but not rubbing alcohol. It can also be sent by itself in an unbreakable container, with no wadding or tissue because that dries it out. The packaged tick can also be delivered to a local Fish and Game office and staff can send it to Beckmen in Fairbanks.

It is critical that some information is provided as well. You can download a “sample submission form” from the Fish and Game website. This form is used for a wide variety of samples – so note on the form this is a tick submission.

Beckmen said a pathologist can look at DNA in the tick sample to determine what diseases the tick might carry. “It’s more specific and easier to detect the pathogen directly in the tick than the antibodies in a person,” she said.

Learn more about ticks in Alaska and the Submit-A-Tick Program:

Printable flyers and more information:

The sample submission form – with contact information for both Gerlach and Beckmen

Tularemia Fact Sheet for Pet Owners (PDF 42 kB)

Wildlife Health & Disease Surveillance Program: dfg.dwc.vet@alaska.gov

Wildlife Health Information Phone: 907-328-8354

Alaska State Veterinarian office: 5251 Dr. MLK Jr. Ave., Anchorage, AK 99507

ADF&G Wildlife Veterinarian address: 1300 College Road, Fairbanks, AK 99701

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and the producer of the Sounds Wild! radio program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.