Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2018

Digging into Common Razor Clam Questions

For many anglers in Southcentral Alaska the transition to spring stirs the thought of making a trip to the Kenai Peninsula to dig razor clams. Planning a trip revolves around the days when we have daylight minus low tides exposing the sandy intertidal clam beaches. The East Cook Inlet shore between the Kasilof and Anchor rivers has historically supported Alaska’s largest sport and personal use razor clam fishery. This fishery has supplied a wide array of memories that often include a clam shovel, five-gallon bucket, deep holes and cold fingers that have a tenuous grip on the siphon of a razor clam seemingly digging its way to China. Memories don’t stop there but continue with sandy wet clothes followed by hours and hours of cleaning by removing guts and sand with copious amounts of water, then settling down to a delectable razor clam meal.

Unfortunately, our East Cook Inlet razor clam fishery has been closed by Emergency Order since 2015 due to low abundances of adult clams. These management actions have been followed by numerous questions from news reporters, clam diggers, researchers and the local communities. The overall theme of these questions has been: “What’s going on with East Cook Inlet razor clams?” Below are some of the more common questions that we’ve been asked and our responses.

What types of data does the Alaska Department of Fish & Game (ADF&G) collect?

We collect data to help us monitor the fishery and assess population trends, which includes the following: 1) total harvest and effort (number of digger-days per season) since 1969; 2) distribution of diggers on area beaches from aerial surveys since 1970; 3) age and length composition of the harvest for most beaches since 1966; 4) periodic abundance surveys from 1989-2008 and annual surveys since 2011 on beaches that have historically supported most of the harvest (Ninilchik and Clam Gulch); and 5) digital imagery of the beaches to assess habitat changes since 2015.

What role did harvest play in the decline?

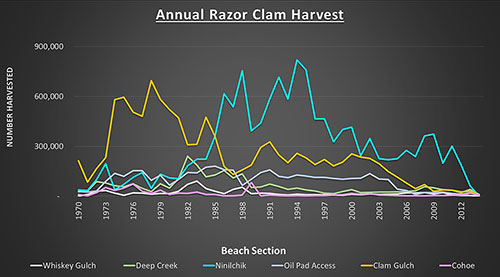

Historically, the East Cook Inlet razor clam stock has supported sustainable harvest opportunities. The historical data and trends suggests little to no fishery effect on most beaches. Digger-effort has not been uniform throughout East Cook Inlet because digger-effort and harvest has been concentrated on the easier to access beaches in Ninilchik and to a lesser extent, Clam Gulch (Figure 1). This results in different harvest rates over the various beaches, with most beaches showing low harvest levels. On the higher harvest beaches at Ninilchik, we tended to see the average age of the harvest to be shifted towards younger razor clams. On moderate harvest beaches such as Clam Gulch, annual recruitment of razor clams to the adult size of approximately 3 inches in length (80mm) was 10 to 20 times greater than the annual harvest. Since the mid-2000s we’ve observed a reduction in the number of razor clam age classes and a shift towards younger clams on all the beaches, regardless of harvest. This suggests that some of the factors that led to the decline in razor clam abundance have happened throughout East Cook Inlet beaches.

Wasn’t the big storm in the fall of 2010 the cause of the razor clam crash?

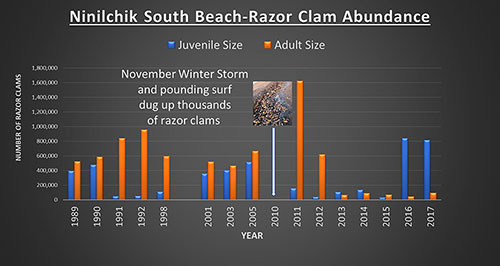

Pounding surf is known to displace razor clams from the sand as was observed on the Ninilchik beach following a big storm in November 2010. What made this event so impressive was the large number of razor clams found dead on the beach. The following spring, abundance surveys conducted on Ninilchik beaches found there were still several million razor clams (Figure 2). Since then, annual abundance surveys at Ninilchik have found poor recruitment of new clams to the beach and high annual natural mortality rates ranging from 40% to over 80%. Both poor recruitment of young clams, and high natural mortality have led to a decrease in productivity of this stock.

How do you estimate abundance?

We estimate razor clam abundance on a given beach through density sampling, then expand the abundance estimate to the total area of that beach. To sample density, we use a water pump to liquify the sand within half-meter circular plots. Any razor clams within the plot will float to the surface for easy capture. We measure the length and count growth rings to age every clam captured before we return the clam alive back into the plot, allowing us to estimate clam densities of both juvenile and adult clams by size and age.

Why didn’t you conduct annual abundance surveys before 2011?

In the Lower Cook Inlet Management Area, which extends south of the Kasilof River, sport fisheries research priorities are identified through annual reviews with regional Fish and Game staff who take into consideration fisheries management information needs, funding scenarios, and potential for collaboration. Through the 1980s and 1990s the data used to assess the East Cook Inlet razor clam fishery and stock indicated that the harvest was sustainable and therefore the stock received a lower research priority. In the late 2000s, more of our limited resources were allocated to higher priority sport fisheries such as Lower Kenai Peninsula freshwater Chinook salmon. Prior to 2011, surveys were conducted throughout the spring and summer months while the clam fishery was underway due to limited funds and personnel.

In 2011, Dr. Brad Harris of Alaska Pacific University (APU) made an inquiry about potential volunteer projects for his undergraduate and graduate marine biology students, while simultaneously the Division of Sport Fish was looking for more hands to help with a spring abundance survey. This partnership is now entering its eighth year. Since its inception we have conducted annual razor clam surveys at Ninilchik, and since 2014 annual surveys at Clam Gulch. This partnership has allowed the division to respond quickly to the precipitous decline in razor clams and the need for annual management actions. Because of this increased survey effort, razor clams research has been elevated to one of our top priorities and now has dedicated division funds.

What is the biology of razor clams?

Overall, the biological processes that sustain clam populations in East Cook Inlet are poorly understood. In general, these clams reach the adult size in 2-5 years. Spawning occurs in late July and August, and larvae drift for up to two months before settling on to sandy beaches. Juvenile razor clams live in the top few inches of the sand which leaves them more exposed to heavy wave action and changes in water temperature than adults.

Are predators and disease an issue?

Both predators and disease could have contributed to the decline of our razor clam populations, but they are not likely the only cause of high rates of natural mortality. Although we have been primarily focused on conducting abundance surveys and assessing habitat with our increased monitoring efforts, we do have some bits of information about predators and disease. Rafts of sea otters have periodically been reported along the beaches and we have observed some evidence of holes presumably dug by otters, but the extent of the predation is unknown. In 2010, a graduate student detected a parasite in the reproductive organs of some razor clams sampled from Clam Gulch. The parasite was never identified, and it is unknown what impact it may have had on the reproduction rates of the population. In the last few summers, we’ve been assessing razor clam maturity, and have not observed these same parasites in our samples.

Is the razor clam population recovering?

Our abundance surveys continue to indicate that adult numbers are still at historically low levels, but we have observed a promising increase in the numbers of juvenile-sized razor clams on Clam Gulch and Ninilchik beaches. We have also observed differences in adult natural mortality rates between years ranging from 40% to 80%, which is higher than what we would expect for the clams to reach historical maximum size or age. As juvenile clams grow to an adult size we will have a better understanding on how these clams can support harvest opportunities and the potential for the stock to fully recover.

What about razor clams on the west side of Cook Inlet?

There are lots of ways to approach answering this question but more importantly it requires more of a discussion than just an answer. Unlike East Cook Inlet, West Cook Inlet is not one continuous sandy beach and razor clams are found in isolated sandy beaches from Harriet Point to Kamishak Bay. Usually when people ask about West Cook Inlet razor clams they are referring to area between Polly Creek and Crescent River Bar. Although this area is the most popular location for sport diggers, most of the harvest that occurs in this area is in a commercial fishery. Access to this area is difficult and requires a large, sea-worthy boat capable of crossing Cook Inlet from Deep Creek, the Kenai or Kasilof areas, or by airplane. In recent years, the Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries have increased monitoring efforts of the razor clam fisheries in this area. Based on the good harvest success in digging razor clams, harvest trends in the commercial fishery, and age and length composition, razor clams in the Polly Creek and Crescent River Bar area are not going through the same downward shift in productivity that’s occurring in East Cook Inlet. And, the harvest in both sport and commercial fisheries is being supported by many age classes including good numbers of large size clams.

So how can you explain the difference in the west side versus the east side productivity?

This is a very difficult question to answer and there are likely multiple environmental factors that are impacting the west side differently than the east side. First, our understanding of productivity in East Cook Inlet comes from long time series data which is not available in West Cook Inlet. The most noticeable difference between these two locations is overall size of the beaches. The East Cook Inlet beach is longer and narrower than the Polly Creek and Crescent River Bar commercial clam beaches on the west side. Preliminary results suggest that there is roughly five times more habitat in the Polly Creek beach alone compared to the entire East Cook Inlet beach. The size, shape, slope, topography and aspect of these beaches likely influence the productivity of razor clams. The division is developing methods to better define razor clam habitat and to assess changes to the beaches. Incorporating this work on both sides of Cook Inlet will help us better understand the similarities and differences between them. We have observed noticeable shifts in the amount of sand on the Ninilchik beaches that correlated with die-offs like the winter storm in 2010, suggesting potential habitat instability on the east side.

What other factors affecting the decline of razor clams has the department considered?

The decline in productivity of other Cook Inlet shellfish stocks and their inability to rebuild after fishery closures may indicate shifting environmental conditions and or changes in habitat. We have considered ocean acidification and warming temperatures, but those don’t seem likely considering we would expect productivity to suffer on both sides of Cook Inlet if that were the case. Loss of sea ice in Cook Inlet resulting in increased surf action on east side beaches has recently been discussed. The division recently began to monitor water temperature year-round in cooperation with an APU graduate student, but so far, we have not detected an obvious correlation. Assessing other environmental conditions in the area, while important, might be more challenging.

What are the future plans for managing the East Cook Inlet razor clam fishery?

The work that was initiated in 2011, where we began honing our research methods and reassembling and standardizing the long term historic data sets, will continue. This will allow us to improve resolution and comparisons within the current datasets and improve resolution and comparisons to datasets collected by other agencies and researchers.

At this point it is difficult to say when the east side razor clam population will be able to support a sport and personal use fishery; however, we are optimistic that East Cook Inlet razor clams will support a fishery again and our focus will be identifying sustainable harvest rates that will allow this stock to fully recover.

The authors are staff in the Division of Sport Fish. Carol Kerkvliet is the Lower Cook Inlet Area Management Biologist, Mike Booz the Lower Cook Inlet Assistant Area Management Biologist and Tim Blackmon, is a Fish and Wildlife Technician and clam crew leader based in Homer. Pat Hansen is the project biometrician based in Anchorage.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.