Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

November 2017

Cougars in Alaska

Every few years Fish and Game gets a report of a cougar sighting in Alaska. In October 2017 a woman reported seeing what she thought was a cougar in Ketchikan. Alaska is considered to be outside the range of cougars (also called mountain lions and panthers), but with cougar populations increasing in many western states and Canada, that could change.

Carnivore biologists in Oregon and Nebraska offered insights into cougars. Nebraska is midway through a five-year study of the big cats to determine their numbers and range in that state. Cougars were native to Nebraska but extirpated in the late 1800s. In 1991 there was a confirmed sighting; the cats gradually became established and numbers have increased in past decades. Biologists there are monitoring the animals by investigating kill sites, tracks, scat, blood traces and hair sign; more than a dozen resident cougars have GPS collars as well.

Oregon offers a good contrast because cougars were never extirpated from the state, and in some areas, people grew up living with them in the surrounding wildlands. In other parts of the state, they are exotic newcomers. Biologists in Oregon estimate that the cougar population there has tripled since the mid-1980s, to about 6,500 animals.

Reports of cougar sightings in Alaska have come from as far west as the Kenai Peninsula, but the most credible reports come from Southeast Alaska, which is adjacent to known populations in Canada. Although the cats are fairly rare in northern British Columbia, biologists estimate there are about 3,500 mountain lions in Southern B.C. - and Vancouver Island has one of the highest densities of mountain lions in the world.

Cougar Sightings in Alaska

Ketchikan-based state wildlife biologist Boyd Porter said that with cougar numbers increasing in much of their historical range, it’s not surprising they would disperse and wander down some of the big river valleys flowing out of Canada. He added that males would be the most likely to disperse and look for new range.

The heavily glaciated coastal mountains are a formidable barrier to movement between Canada and Southeast Alaska. The most prominent “trans-boundary” river in Southeast Alaska is the Stikine, which cuts through the mountains and meets the Inside Passage between Petersburg and Wrangell. A little further south, the Unuk River, about halfway between Wrangell and Ketchikan, provides another narrower corridor.

Wildlife technician Micah Sangenetti works in Ketchikan with Porter. He’s familiar with both river valleys. He said a cougar could come down the Stikine, or the Unuk, which is closer but narrower. Ketchikan is on Revillagigedo Island (often called Revilla Island for short). In either case a cat would need to cross a narrow saltwater passage, Behm Canal, to reach the island.

“The Stikine River drainage is like a superhighway compared to the alley that is the Unuk,” Sangenetti said. “The Stikine is a wide valley, which cuts through the coastal range much further into the Interior. That’s the same reason moose are making it to Mitkof and Kupreanof (Islands), whereas the Unuk River’s source begins in the Coast Range.”

The only known cougars to be killed in Alaska were taken near the Stikine River. In December 1998 a wolf trapper snared a mountain lion on South Kupreanof Island, and in November 1989 a mountain lion was shot near Wrangell.

State wildlife biologist Rich Lowell of Petersburg said he used to get one or two reports of cougar sightings each year, but it’s been quiet recently. “The last reliable sighting we received was a few years ago when a Stikine River moose hunter said he had a cougar leap down from a tree very close to him and run off. He said another hunter had also reported seeing a cougar around the same time.”

Boyd Porter said there have been a handful of credible sightings in the Meyers Chuck area of the Cleveland Peninsula, a wild, unpopulated area between Wrangell and Ketchikan. Both the Stikine and the Unuk rivers could provide access. On April 20, 1998, a cougar was photographed at night at Meyers Chuck, on the Cleveland Peninsula.

Porter said he received several credible reports of cougar sightings in 2010 and 2011 about 25 miles north of Ketchikan, not too far from the Unuk River. In November of 2010 two Ketchikan deer hunters near Traitors Cove watched a cougar from just about 75 yards away, describing the animal in good detail. Porter said a few weeks later, another hunter in the area and unaware of the earlier sighting, reported tracks. “That same fall a local hunter reported hunting the Margaret area and calling for deer in November. When he finished calling late one evening and started hiking back to the vehicle in the fresh snow he found fresh cat tracks circling the area he had been calling deer from.”

Another report came in the following year, and Porter believes it was the same animal.

In the northern Southeast Alaska, the Taku River is a good corridor to the coast from British Columbia. About 100 miles further north the Skagway River and the Klondike Highway connect the coast with British Columbia.

State wildlife biologist Neil Barten said in the summer of 2000 he received a credible report of a mountain lion at Snettisham south of Juneau, and just south of the Taku River. A worker at the fish hatchery there reported that he had seen a cougar stalking geese on the tide flats on several occasions, and also saw tracks around the staff quarters. Barten said a report came from a state wildlife trooper working in Skagway in 2002, who watched a cougar walking down a quiet Skagway street in the middle of the night.

It is known that moose use these river corridors to access coastal areas from Canada. Fishers, house-cat-size weasels, seem to be pushing the boundaries of their range in Canada and making forays into Southeast Alaska via these corridors as well. Trappers targeting marten incidentally caught three fishers in the Juneau area in the 1990s. Around 2012 an open season was created for fishers, in part to encourage reporting. Since 2013, trappers have reported catching 12 fishers on the northern Southeast Alaska mainland.

Nick Demma is a large carnivore research biologist for Fish and Game. He said another potential cougar immigration route to consider is the Alaska Highway Corridor, entering Eastern Interior Alaska north of the Nutzotin Mountains. Mule deer are sometimes reported in Eastern Interior Alaska, and one was found road-killed outside of Fairbanks in May of 2017. Demma wrote: “As mule deer sightings in that region appear to be increasing and because they are a main prey of cougars where they co-exist, and because both source populations exist next door in the Yukon it is certainly reasonable to expect that cougars would follow an expanding mule deer population into that part of Alaska as well.”

The Yukon Territory was considered to be outside the cougars range until recently. The first confirmed sighting in the Yukon was in 2000. The Canadian Broadcast Corporation reported in 2015 that two cougars were photographed just outside of Whitehorse in May 2015, and there is now evidence of a small, established breeding population in the Yukon.

Dispersing Cougars and Establishing Populations

Sam Wilson is a furbearer and carnivore biologist with Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. He’s studying cougars and said the animals are capable travelers.

“Many young males disperse long distances,” he said. “And by long distances I mean hundreds and even thousands of miles.” He said a cougar was documented moving from the Black Hills of South Dakota to Connecticut. He said females also disperse, but tend to set up their own home ranges adjacent to or even overlapping their mother’s home range, the “natal” home range where they grew up.

The cougars that stay in Nebraska are mostly becoming established on the west side of the state by the Wyoming border, which provides the best cougar habitat in the state. Wyoming offers the source population. “Wyoming has an established cougar population that was never extirpated, and the country is steep and forested,” Wilson said. “To the east of that is short grass prairie, and it’s not suitable habitat for lions. There are not high deer densities or the rough terrain or forests to use to ambush prey. They can cross the prairie on dispersal events - dispersers can cross any kind of habitat.”

He said cougars swim rivers when they need to. “There is no other way they could get to areas where they are documented,” he said.

In Oregon, where cougars were never extirpated, the cats disperse from high-quality habitat in the Blue and Wallowa Mountains of Eastern Oregon, and from populations in the Cascades, the prominent volcanic mountains that divide eastern and western Oregon. Biologist Derek Broman is the coordinator of the Carnivore and Furbearer Program with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. He’s involved in research and management, and educating people on how to coexist with cougars.

“The La Grande area (northeast Oregon) has had robust cougar populations for years; a cougar runs across the road in front of someone and they might not even tell their neighbor, they are old hands,” he said. “There are cougars showing up in in the Willamette Valley, showing up in Portland suburbs, and people are freaking out and don’t know what to do. They assume it’s a bad thing."

He said one of his challenges is to take the knowledge of people who have lived with cougars for decades and share that with people in areas where cougars are new.

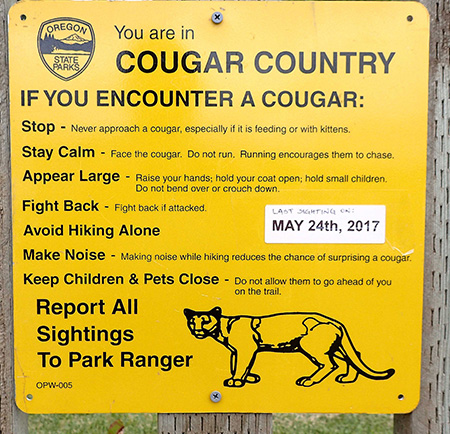

Broman said Oregon media has been helpful in sharing safety information and “living with wildlife” messages. There has never been a fatal cougar attack in Oregon, and he said biologists there have been actively studying cougars for more than 40 years. He said the state biologist in Newport is involved in a new study of the cats on the Oregon Coast.

Cougars generally disperse from their mothers between 9 and 21 months of age. In Oregon, railroad tracks are a common corridor for the cats, Broman said. Youngsters looking for a new area make the best of what’s left, after dominant animals take the better habitat.

Oregon does have a “new” animal colonizing the state – the wolf – and Broman is curious to see how the two predators will adapt to one another.

“It’s going to be interesting to see what happens with these wolves expanding across the state and how that affects the cougar population, if they’re no longer the apex of the apex predators,” Broman said. He thinks it’s likely that they’ll exploit the habitat they’re best at, rocky, broken country where they can ambush their prey, compared to wolves that prefer more open country because they tend to chase their prey down.

That highlights a challenge any young cougar would face dispersing to Alaska – a landscape already well-occupied with black bears, brown bears, lynx and wolves.

Mistaken for Cougars & What to Look For

Last summer a woman called me to report a cougar sighting in a neighborhood north of Juneau. That morning her husband has seen a big yellow animal with a long tail bound across the road and disappear into the woods.

I made some calls and rounded up three trail cameras. A coworker mentioned that a friend had related a similar experience a few days earlier in the same neighborhood. Before I drove out the road, I called the woman to help me identify some good places to set up the cameras. She said not to worry.

She and her husband had walked around talking to neighbors, and discovered a contractor working on a house. He had a big yellow dog with a long tail, running loose. They realized it was their cougar.

Both Wilson and Broman said dogs are very often the cause of a “false alarm.” The color of the animal is often the first thing people note, and that can be a dog, a deer or even a housecat. Wilson said in Nebraska, coyotes and bobcats are also mistaken for cougars.

“Sometimes the person will identify the animal at a distance, often at dawn or dusk, and the animal is running or the person is driving,” Wilson said.

Broman said scale can be confusing, and people mistake housecats for mountain lions. People have reported black panthers. “There has never been a melanistic cougar documented in Oregon,” he said. “It’s being able to tell the difference between a cougar and a housecat. Mountain lions have small heads compared to their big, heavy bodies. You need an indicator of scale. You see something walking through a field, go out and see how tall the grass is. You might think it’s two feet tall and it’s three inches tall.

“Even hunters do it – they think a bear is huge and come up on it and it’s a yearling. If something ran across the road, stop and look at how tall the vegetation is beside the road. Is that leaf there the size of your hand or bigger than your head?”

He said people commonly mention the animal’s long tail. “There is always the long tail, but not further details. Was it pointed straight up, does it have a curve? A cougar doesn’t carry its tail like a housecat.”

Mountain lion sightings in Alaska sometimes turn out to be lynx - for good reason. Lynx can cover a lot of ground and are found throughout much of the state. They are better adapted for cold weather, with short-tails, heavy fur coats, ear tufts and oversized, snowshoe-like paws. In the winter of 2001 a Palmer resident reported a mountain lion was eating his domestic rabbits. The area biologist collected hair samples, and DNA analysis revealed the cat was a lynx. Cougars average 100 to 150 pounds and are three to five times bigger than lynx.

Bobcats, the lynx' smaller cousin, barely range north of the U.S.-Canada border.

The Real Thing

The sighting in Ketchikan in October was a fairly brief glimpse. Wilson said in Nebraska, they consider a sighting confirmed if there is tangible evidence: tracks, scat, mountain lion hair, or pictures on a trail camera. Trail cameras are popular in Nebraska, and he said there are thousands – maybe tens of thousands - of trail cameras in use.

A kill site, usually a dead deer, offers a wealth of clues.

“Lions often cache their prey, bury it in grass or leaves,” Wilson said. “Bobcats also do this, but in many cases we find tracks and other evidence because they spend a lot of time there. We do look at how the animal was killed, lions often kill with a bite to the back of the head or the throat, and we put all the clues together. And often we’ll put a trail camera on it because they come back.”

Broman said the use of trail cameras is increasing in Oregon as well, giving people the opportunity to “see” elusive animals like cougars, “There’s a growing interest in tracks and signs,” he said. “It’s like a new version of birdwatching, people look at tracks and signs and add them to their life list.”

A trail camera image of a cougar in Alaska would be a welcome piece of tangible evidence. Ketchikan biologist Boyd Porter encouraged anyone who believes they’ve seen a cougar to get a photograph and send it his way.

More on Cougars:

The Oregon Cougar Management Plan offers a wealth of information on cougars

Oregon is cougar country brochure

The cougar that traveled from South Dakota to Connecticut

The Cougar Network: The Cougar Network is a nonprofit research organization dedicated to studying cougar-habitat relationships and the role of cougars in ecosystems. The website offers a database and map of cougar presence outside of western cougar range dating back to 1990.

Cougars expanding their range into the Yukon

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News. He lived in La Grande, Oregon for eight years growing up and never saw a cougar, but if he had he would've told his neighbor.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.