Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2016

Hazing Brown Bears at Port Armstrong

Tasering brown bears and shooting them with paintballs smacks of a goofy Alaska reality TV show, but it’s far from it. It’s part of a project that’s saving bears’ lives and keeping people safe.

State Fish and Game biologist Phil Mooney and his colleagues have tazed more than 300 bears, and paintballed more than 100 at Port Armstrong, near Sitka, since 2010. They are teaching the animals to stay out of areas where they don’t belong — an option vastly preferable to killing them.

“Hazing is a short term action intended to have a direct response — to change their behavior and get them out instantly,” Mooney said. “It can be a one-time event or part of adverse conditioning, teaching them to move off when people come out. They are really quick to learn, and the more you’re around them the more you appreciate it.”

A brown bear can hit 40 miles an hour in about 16 feet from a dead stop and outrun a quarter horse in a 100-yard dash. It can discern color better than a chimpanzee, and their sense of smell is among the best in the animal world. “Their nose is seven times better than a bloodhound,” Mooney said. “They learn by watching. If you’ve had a dog for a long time, you know how smart they are. Bears are smarter than dogs.”

Bears are also really sensitive to each other, to posturing, and to social status among bears, Mooney said. He and his colleagues apply their understanding of bear hierarchy, and what motivates and discourages them, to keep them out of trouble at Port Armstrong.

Port Armstrong and Brown Bears

Port Armstrong is at the southern end of Baranof Island in Southeast Alaska, and the fish hatchery and adjacent salmon stream are powerful draws for brown bears. Manager Ben Contag once counted 36 individual bears in his two-minute walk to work. Bears out on the beach, in the creek below the weir and in the forest are fine, bears on the boardwalk and in the work areas are not. Over the years, hatchery staff have tried electric fences, whistles, seal bombs, cracker shells, pepper spray, a giant potato gun, yelling and screaming, and—as a rare last resort—shooting to kill under Defense of Life and Property rules.

The hatchery produces more than 100 million salmon annually, mostly pink and chum. As a yearly glut of fish crowds the mouth of a short stream, scores of bears show up as this the largest accumulation of spawning fish available for miles. The bear numbers have grown over the years as generations of cubs raised on hatchery fish returned as adults, many with their own cubs in tow. Humans include a handful of seasonal workers and seven year-round staff. Though outnumbered by bears, they’ve built comfortable, albeit well-fortified, lives in trim homes lining the boardwalk.

“When we showed up for paintball marking in August (2015) we had 26 bears on site,” Mooney said. “When we came back in October, we had 18 on site and as soon as we showed up, they remembered us and our scent, and they went nocturnal. The thing about Port Armstrong is they have that late coho run and the bears know it. By mid-October it’s typical for sows and cubs to be gone, but not there. They stay up.”

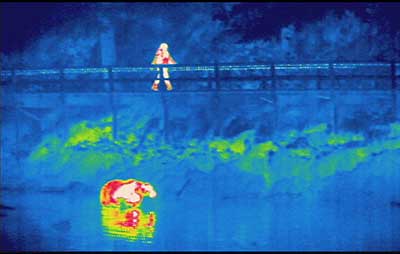

In the past, going nocturnal meant bears could sneak into the off-limits areas in the dark, but not anymore. The biologist can work in the dark using forward looking infrared devices, commonly called FLIR. Typically this is a camera, and the thermal imaging capability allows the user to see bears at night because they are warmer than the surroundings.

“Bears have good eyesight at night and good noses, they don’t need a flashlight,” Mooney said. “That FLIR is really effective, and they can’t figure out how you can see them.”

A big concern is not a deliberate mauling, but instead an accidental crash encounter.

“Before we started hazing, there would be times where the bears were pretty close to the workers, not interfering but potentially dangerous,” Mooney said. “You don’t want to get run over by a bear. When there are 15 to 20 bears, there’s a lot of bear to bear interaction, and they push each other around. There are sows and cubs. You’ll see a younger bear with a fish and a bigger bear will approach him, the younger bear will just spit out the fish and leave, he can always catch another fish and doesn’t want to fight. If a bear is fleeing and you’re in the way, you’re going to get run over.”

Bears pushing bears around might put a bear in an off-limits area by mistake, and there’s no point in hazing that animal.

“You have to give the bear an avenue of escape, that’s the number one rule,” Mooney said. “If it has been pushed into the work area by another bear, it just wants out, we don’t need to hit him, he’s trying to leave.”

The biggest males tend to dominate, and they can demand respect. Mooney recalled one big male walking down the beach, and the other bears moved into the woods. If they didn’t, he’d start toward them, resuming his travel when they backed away. One bear near the water didn’t leave, and the big bear went after him. Turns out the second bear had no problem being chased into the water.

“He was a great swimmer,” Mooney said. “You’d see him swimming with his head underwater, looking for fish. When that big bear came after him in the water, he literally started swimming circles around him. He knew he could outswim him. The big bear gave up, and they both went back to the beach, and it happened a second time. After that he left him alone.”

Mostly, the bears are live-and-let live. But those expressions of dominance are important to the bears, Mooney said.

“One night there were six adult females, with cubs all mixed in, everybody’s fishing and everybody’s happy,” he said. “We’re watching them, and we hear this low sound, not a roar, like a quiet rumble. There’s this big bear under the boardwalk and everybody immediately looks over, and leaves.”

Mooney and his ADF&G colleagues, primarily Larry Lewis and Neil Barten, use the bears’ sensitivity to hierarchy to their advantage. Tasers essentially make them the biggest bears on the beach.

“We recorded the audio of a big bear in trouble, a big roar after being hit by a Taser,” Mooney said. “We played that audio back, and noticed they moved off. They appear to know that if he’s in trouble, it must be bad news. We’ve cleared the tide flat simply playing that audio.”

Tasers

Taser is a brand name for what’s technically called a conducted electrical weapon made by Taser International. The Taser fires a pair of small, dart-like probes that are connected back to the device with conductive wires. A nine-volt battery in the handle provides the power. Upon contact, an electrical current pulses between the two probes and disrupts the body’s voluntary control of muscles, causing what’s known as neuromuscular incapacitation (NMI).

“They lock up mid-step and go down,” Mooney said. “The device has overridden the brain’s ability to control the voluntary muscles, and the muscles don’t know what to do. You can yell, and breath, but you can’t get up. It stings and it is briefly painful. It breaks the fight or flight response.”

Biologists are now using the newest X2 Taser, a law enforcement model. The cartridge range is up to about 35 feet. A cartridge with the probes and wires attaches to the front, then a burst of compressed nitrogen gas fires the probes. “At 30 feet the two probes are about 28 inches apart, that’s the circuit,” Mooney said. “The more muscle mass you have across there, the better they lock up. It’s not the voltage, it’s the pulse. There is electric energy conducted to the muscles, 19 pulses per second, and it interrupts or overrides the signal from the brain to the muscles.”

The current continues as long as the “on” switch is activated, for up to 60 seconds. For hazing, the typical jolt is usually three to five seconds. Tasers have been used to immobilize wildlife like bears, moose and deer for brief periods, 10 to 15 seconds, to free them from entanglements or administer an injection, but that’s not the case with hazing. They are just sending a message to the bears, Mooney said. They also yell at the bears, so they associate yelling with the experience.

“You can see it in the bear’s eye, they can’t figure out what is happening,” he said. “They understand posturing. It’s a big part of it. They’re down, you are standing up, yelling at them, then you let off and they get up and run. You flip that switch, it’s off. Having done it now hundreds of times, it’s almost instant — the longest I think any of us has held a bear down is seven seconds. They learn. We are the aggressors, and they know that. After they’ve been hit once or twice, or seen other bears hit, they’re sensitive.”

“We don’t care if they’re out on the downstream side of the weir, they can come anyplace there and fish, we just don’t want them in the work area, and we want them sensitive enough that they move off when people come out.”

Mooney and his colleagues have modified their protocol as they’ve learned more about bears, and as they bears have adapted to them. At first, the main rule was never taze a bear that’s standing in water, to avoid any possible drowning. “Then we learned that as long as their head isn’t near the water, we could hit them, and then instantly let them up,” Mooney said. “They stumble in a blitz of NMI, are ‘released’ as the switch is flipped ‘off,’ and they get the message.”

Paintballs

Shooting bears with paintballs serves two purposes. It enables the biologists and hatchery workers to identify individual bears, and it is a hazing action as well. The paintball “projector” can shoot a paintball 70 feet, but most shots are 15 to 30 feet, Mooney said.

Marking is particularly important because of cubs’ personalities. While bears often have distinguishing markings — a natal collar or distinctive ear coloring — often bears are wet, the light is dim, and they are similar size. A three-year-old cub can be almost as big as an adult, although not as heavy.

“There are so many sow/cub combinations at Port Armstrong that we needed a way to identify them, especially older subadults,” Mooney said. “If a sow has multiple cubs, you have one that’s always the leader. It doesn’t s matter if it's a litter of dogs or cats, one is the leader. And often, that’s the cub that gets into trouble with people, pushing too close. Then the sow comes in defensively to protect the cub, and that can get her killed. We try to figure out who is who, and target that particular cub.”

If the sow is killed, all the cubs will likely die without her. Mooney said in the past, sometimes the best option has been to take out that one problem cub, to save the sow and the other cubs, because that one cub will get them all killed.

Bears are constantly in and out of the salt water, so biologists are using an oil based paint, which holds up well. Green, blue, orange, yellow and red are most visible. After about six weeks hair growth covers and shadows the color spot.

“Even at night, you can tell there’s a mark, but not the color,” Mooney said. “It’s the same with a collar, you can’t see it, but it blocks the heat and you can tell it’s a collared bear.”

Lasers and the Potato Bazooka

The biologists and the folks at Port Armstrong have an arsenal of tools for dealing with bears that goes beyond Tasers and paintballs. Electric fences are pretty effective — but in some areas the tide comes up too high. In some cases they’ll string a single “hot” wire to protect an area at Port Armstrong. But electric fences have their limitations.

“Electric fences work, but if you put a pile of food out and put a fence around it, bears will figure it out and get the food,” Mooney said. “They’ll fight the fence. They get stung, and run, but they’ll come back and figure it out. Bears are persistent. If you’re in a tent with no food, and you have an electric fence, there’s not much incentive for them to get in. If there’s food, they’re really motivated.”

The Taser can also deliver a shock. With the cartridge removed from the front, it can be used as a hand-held electrical arc generator.

“There’s an arc stun button, and that’s different than the probes and the neuromuscular incapacitation — that is a shock,” Mooney said. “The whole thing ripples across the face of the Taser, and has an electric sound, a distinct clacking noise. And I think they can smell the ozone. They don’t like the combination.”

Mooney has simply shown the bears the arc and had them stop in their tracks, and even turn and run. He thinks bears have an inherent fear of electricity. It’s a bit mysterious, he admits, because lightning storms are extremely rare in Southeast Alaska.

“Down south, in the West, animals see lightning, and seem to know what it is. You can see it with horses, they don’t like it,” he said. “But how do these bears know? They just don’t like it either.”

He thinks that’s also why they don’t like blue laser light.

“We’re also using laser lights, basically powerful laser pointers, and the bears really don’t like the blue color,” Mooney said. “They don’t mind other colors; they appear attracted to the green laser light, like a cat. But the blue — you shine it at their feet they move off. We don’t shine it in their faces or eyes.”

Bears are sensitive to sounds, and there are several commercial devices to repel deer, bears and wildlife, primarily from gardens. Mooney has found one design to be most effective. Because animals quickly learn that a noise is not harmful, the small, motion-triggered device uses a combination of different sounds and lights; high pitched sounds, people yelling and screaming, different colored lights, and it resets for a different pattern so animals don’t become accustomed to one pattern. The strobe lights, he said, are particularly effective.

Then, there was the experiment with the potato bazooka.

“It would really throw a potato out there,” Mooney said. “The first time someone nailed a bear, it whacked it pretty good. He jumped, but then when he turned around to come back and see what hit him, and it was a potato, he picked it up and ate it. Now they were technically feeding a bear. We didn’t want a situation where bears started lining up waiting to be shot with a potato. They tried a quarter pound piece of modeling clay, and the bears would just take the hit. It worked for a couple hits, but then they figure out there’s no significant damage.”

The Taser has proved to be the big stick that backs up the warnings. Mooney has seen things like the potato gun and rubber bullets fail, but not the Taser.

“We’ve now exposed approximately 325 brown bears successfully to the Taser,” Mooney said. “We’ve achieved one hundred percent flight response. No bear has ever stood and taken a second shot, yet. I wouldn’t say it’s not possible, but it hasn’t happened yet. Originally the fear was you shoot a bear, and they turn around and come back — you smack a sow with cubs a lot of time she’ll come back defensively. But not with the Taser, we’ve never had one re-approach us.”

“Ben and his crew have the ‘power’ now; they can pick out a bear that’s causing problems and target him, that one cub that is going to get mom and the other cubs killed.” Mooney said. “The goal was to protect people down there and not unnecessarily destroy bears. We were talking, and we’ve estimated that since 2010 we saved about 40 sows and cubs, bears that would have been killed because they were just too persistent.”

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild radio program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.