Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

July 2015

Zebra mussels in Alaska? Not yet.

Invasive mollusks are spreading among lakes and rivers in the Lower 48, causing a host of problems. Late last year, Alaska dodged two potential introductions of these invasive species on boats bound for the state.

You may have heard of zebra mussels and the devastation they’ve done in the Great Lakes over the past decade. Some argue that zebra mussels were a godsend, “Cleaning up Lake Erie, and all.” They definitely increased the clarity of the Great Lakes, which had become polluted by industrialization and pre-Clean Water Act regulations in the Rust Belt. But while the mussels were filtering out the pollution, they were also effectively eliminating the foundation of the aquatic food web by devouring plankton.

Native to the Caspian Sea, zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) were first found in North America in 1988. It’s believed that they were brought in when ballast water, taken up from western European ports, was discharged into ports within the Great Lakes. Zebra mussels were first detected clinging to rocks, piers, and other structures in Lake St. Clair, which connects lakes Erie and Huron. By 1990, all five Great Lakes were infested. Over the next two years, zebra mussels were found in the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, as well as six other systems connected to the Great Lakes by canals. Barges were thought to have moved the mussels to locations within the extensive canal system. By 2011, 30 of the 50 U.S. states had infested waters in or adjacent to their state. All told, over 600 lakes and reservoirs have zebra mussel infestations in the U.S. The spread of zebra mussels across the U.S. is a classic example of how a nonnative organism can invade and overwhelm a variety of ecosystems.

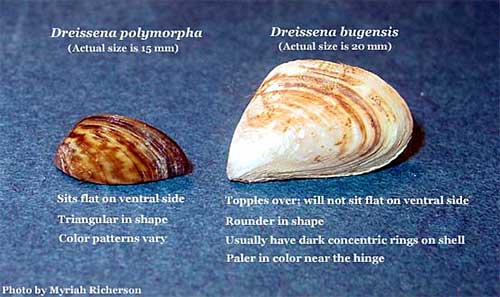

Quagga mussels (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis), a cousin of the zebra mussel, probably arrived to the U.S. at the same time as zebra mussels. They, too, were initially limited to the Great Lakes but in 2007 quaggas were found in Lake Mead on the Colorado River in Nevada. Quagga mussels have since been detected in 15 states.

Dreissenid mussels (zebra and quagga mussels) are harmful, highly invasive freshwater mollusks. The arrival of dreissenid mussels and the damage they cause cities and ecosystems in the Great Lakes region has focused much attention on the ballast water of cargo ships as a major source for invasive species introductions. But now we know that the overland transport of trailered boats played a significant role in moving mussels from the Great Lakes to lakes throughout the contiguous U.S. and resulted in a jump from the Midwest to waters in the West.

Once introduced into favorable conditions, and in the absence of natural predators, dreissenid mussel colonies rapidly expand. Alaska waters would provide suitable habitat parameters to allow zebra or quagga mussels to survive, and a lack of predators to keep their populations in check. They disrupt aquatic food chains, ecological community structure, and they displace native species. By causing declines in forage fish populations that rely on plankton, they impact the entire food web. That clear water I mentioned as a bonus to infestation by zebra mussels allows more light to penetrate the lake allowing aquatic plants to establish in deeper water. When a freshwater system is out of balance, toxic algal blooms also become a more significant problem.

These invasive mussels are striped, freshwater bivalves that can live for three to five years. In a single breeding cycle, each female mussel can release 30,000 to 40,000 fertilized eggs that means a total of approximately 1 million eggs per year. As free floating larvae, dreissenid mussels must settle out and attach to a hard surface in order to begin feeding. By producing their own waterproof glue, they secure themselves against water currents that might otherwise wash them away. Dreissenid mussels attach themselves to just about any stable hard surface available in the water: rocks, discarded cans or glass bottles, piers, and harbor structures. Once attached, they go about filter-feeding on plankton and other tiny food particles - the same food that nourishes native species. Enough of these voracious filter-feeders can cause the decline of an ecosystem.

In the last two months of 2014, The Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) invasive species program received notification of two dreissenid mussel infested boats that had been intercepted at inspection stations outside of Alaska. This is notable because in the previous ten months of last year, we received zero reports of infested boats heading to AK. Luckily, ADF&G has open lines of communication with natural resource agency staff in the western U.S. and Canada. The inspection stations in western states and Canadian provinces which are set up to examine trailered watercraft, provide a line of defense against dreissenid mussel introductions.

On November 28th I received an email alerting me that a boat from Michigan - destined for Alaska - was inspected at the Blythe Border Protection Station by the California Department of Food and Agriculture and was found to have quagga mussels attached. The boat was decontaminated in California and sent on its way.

A week later, I learned from Alberta’s invasive species program coordinator, that a boat en route from Michigan to Alaska was intercepted at the Coutt’s border crossing between Montana and Alberta, Canada. Zebra mussels were found clinging to the hull of the boat. The boat was decontaminated and sent on its way.

“This is a timely reminder that anyone who transports watercraft must ensure their boats are clean and free of stowaway mussels prior to travel,” said Kyle Fawcett, the minister in charge of Alberta’s Environment and Sustainable Resources Development, in a release.

One might suggest the problem is in Michigan, and if you’re talking about dreissenid mussel infested waters, you’re right. The Midwestern states have many waterbodies that have been impacted. Let’s not let that happen in Alaska. Although ADF&G has not received a single report of nonnative mussels detected in freshwaters of the state, we know that the highly invasive aquatic plants, Elodea canadensis and Elodea nuttallii, have been introduced into 20 lakes in Alaska. We also know that invasive species can hitchhike on trailered boats.

In 2012, Dan Bogan, an aquatic ecologist with the Alaska Natural Heritage Program at the University of Alaska Anchorage did surveys for dreissenid mussels in 25 lakes accessible by the road system in Southcentral Alaska. He prioritized which lakes should be surveyed based on the presence of public boat launches, the proximity to the Canadian border, use by anglers, and lakes having calcium concentrations within the suitable range for dreissenid mussels. Fortunately, no dreissenid mussels were detected during the course of his sampling.

In addition to the environmental impacts that could devastate fisheries valued by recreational, commercial and subsistence users, dreissenid mussels could cause significant economic impacts as well. Mussels foul and clog pipes, pumps, water intake structures, power plant intakes, cooling systems and fish screens thereby impacting the ability of water agencies to deliver drinking water and utilities to customers. Impacts to hydroelectricity infrastructure, and cleaning and maintenance costs are passed on to the customers. Public property values can be affected as well.

Boat ramps and harbor facilities get fouled by mussels, beaches littered with sharp shells and the smell of decomposing mussels displace the public. Boat engines and steering components are damaged when mussels are present.

The cumulative impacts of zebra mussels make it worth our time and effort to clean our boats after a day of boating in Alaska or when we’re out-of-state. Prevention is the first line of defense to keep dreissenid mussels out of Alaska. Please remember to Clean, Drain, and Dry your boat and gear every time!

CLEAN- Rinse and remove any mud, sediment, and/or plant material from all gear, boats, and boat trailers, floatplane rudders and floats, and anything that comes into contact with the water. Use a stiff bristle brush to clean your gear.

DRAIN- Empty all water from bilge pumps, buckets, coolers, and wring out gear before leaving the boat launch or lake.

DRY- Completely dry your gear and equipment between waterbodies or trips. Use a towel or sponge to wipe down wet surfaces.

If you travel with your boat in the lower 48 or Canada and visit known dreissenid mussel infested waters, be sure to clean your boat thoroughly, don’t bring home unwanted hitchhikers. Do your part to prevent the introduction of invasive species into Alaska waters!

Tammy Davis is the Invasive Species Program Coordinator for the ADF&G Sport Fish Division

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.