Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

June 2014

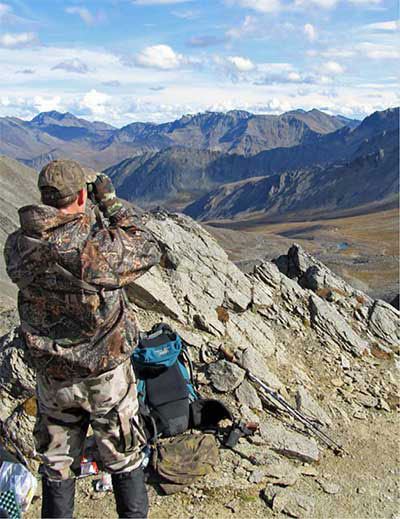

The Economic Importance of Alaska’s Wildlife

Wildlife Generates Billions for Alaska

While it’s not surprising that wildlife is important economically, the scale is amazing. The non-monetary value is also profound – most Alaskans cite wildlife as a significantly important reason for living here.

The details came out earlier this year in study launched by the Division of Wildlife Conservation. About two years of work went into the project, and a summary of the report, The Economic Importance of Alaska’s Wildlife in 2011, indicates that spending on hunting and wildlife viewing totaled $3.4 billion in 2011 and generated $4.1 billion in economic activity in Alaska.

While it’s important for Fish and Game to measure the significance, follow the money and dig into the details, this isn’t a surprise to people like Sherry Brock of Nome. She works at Dredge #7 Inn, a 28-room hotel in Nome. May was booked pretty solid and June is sold out – thanks to birds.

“We’re full-up for the entire month of June with birders,” she said. “We have a lot of foreigners from England, Australia, Japan and Italy coming up for birding. One person rented eight or ten rooms for a group.”

Many are return visitors, she said, and they’re not just spending money on rooms. “They eat, they shop, and they rent cars from us.”

To better understand how much money this means for Alaska businesses, Fish and Game turned to experts. ECONorthwest, based in Oregon, provided a team of economists, analysts, and survey researchers to work with Wildlife Conservation staff. The division’s assistant director Maria Gladziszewski served as project manager. The core data for the report’s economic analysis come from surveys conducted in 2012 that gathered information from about 7,000 residents and 2,000 visitors through surveys conducted by phone, over the internet, and by mail. Additional information comes from key informants with knowledge about the wildlife-economy relationship and a review of related literature.

Generating money

Spending on hunting and viewing totaled $3.4 billion in 2011 but generated $4.1 billion in economic activity in the state, more than 27,000 jobs and $1.4 billion in labor income. How does that work?

Two moose hunters leave their homes in Fairbanks and head to the local sporting goods store where they buy hunting licenses, ammunition, new hunting boot insoles, a spotting scope, and some game bags. They grab sandwiches and sodas at the local grocery store, and fill their trucks and four–wheeler tanks with gas. Early the next morning, they put their four-wheelers in their truck beds and drive to their secret spot to begin their search for moose.

The money the hunters and wildlife viewers spend goes to work almost immediately. It goes to pay the wages of the sporting goods store sales clerk, for example, who in turn spends some of those wages at a local restaurant and some more to pay his utility bill. The money ripples outward in many directions through the local economy, even to sectors not directly related to hunting or viewing. The cycle continues until all the initial hunting and viewing spending eventually leaks out of the economy.

Almost one million households—residents and visitors—took at least one trip in 2011 to hunt or view wildlife in Alaska. Of those, more than 100,000 households, 86 percent of them Alaska residents, went hunting. Almost 900,000 households, 77 percent of them visitors, went wildlife viewing.

About 37 percent of all resident households took at least one hunting trip, and they averaged 11 trips during the year. About two percent of the visitor households hunted, with most taking only one trip. About 77 percent of all resident households took at least one trip to view wildlife, and they averaged 30 trips during the year. About 86 percent of visitors participated in wildlife viewing and averaged 1.4 trips per household (for example, side trips from a cruise).

More money to be made

The report also offers some potential insights for businesses, as part of the study details how much more money people are willing to spend.

The study implies there is potential for more money to be made from people’s desire to hunt and view wildlife.

“We asked both hunters and viewers how much they paid for their trip,” Gladziszewski said. “We asked if, for example, gas had cost a certain amount more, would you still have gone – yes or no. If they said yes, we asked if they would have paid twice as much; if no, we asked if they’d have paid half as much. That gives you a sense for people’s willingness to pay for a trip.”

On average, resident hunters said they would spend about 34 percent more, and resident viewers would be willing to spend 25 percent more. Nonresident hunters would be willing to spend seven percent more, and nonresident viewers 14 percent more.

“That makes sense,” Gladziszewski said. “Visitors are already paying more for their trip to Alaska. They’re willing to pay a little more, but their trip is already expensive.”

Hunters most commonly targeted moose, caribou, black bear, and brown bear. Wildlife viewers, especially visitors, also wanted to see those species, as well as seabirds, birds of prey, and marine mammals. The study explored an interesting aspect of the economic value of these Alaska animals and birds that also demonstrates their intrinsic value to state residents.

“We asked Alaskans if they’d be willing to pay into a theoretical conservation fund to keep wildlife, and many said yes,” Gladziszewski said. “When we asked about contributions to a fund for specific animals, they say they’d be willing to pay more money than when you ask about a general wildlife fund. That explains why all those conservation groups always target a specific animal – save the tiger, for example.”

Quality of life

Wildlife makes an essential contribution to the quality of life for most Alaskans. For 65 percent of Alaskans, wildlife’s contribution to their quality of life is either “extremely important” or “very important.” The contribution of wildlife to the quality of life of Alaskans is especially important in the Southwestern region, where almost 80 percent ranked wildlife as extremely or very important. About half the Alaskans who indicated that they are neither hunters or wildlife viewers still ranked wildlife as very important to their quality of life. In addition, the majority of Alaskans say that wildlife is an important factor in their decision to live in Alaska. Only three to seven percent said that wildlife was not at all important in their decision to live in Alaska.

The full report and appendices include complete results of The Economic Importance of Alaska’s Wildlife in 2011 along with detailed descriptions of the study’s methods and data sources. To download a PDF copy of the full report and its appendices, visit ADF&G’s webpage, http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=ongoingissues.economicstudy

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.