Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2010

Quest for Fire

Planning a Prescribed Burn

Plans for a prescribed fire this spring to improve moose habitat near Fairbanks have some picturing a raging inferno, with wind-driven flames leaping from tree crown to tree crown in the spruce of the boreal forest.

Biologist Dale Haggstrom has a different picture: A ground fire consuming last year’s dried grass and leaves on the greening slopes above the treeline in foothills of the Alaska Range, hopefully scorching subalpine willow stands enough to promote new growth.

“Some people are afraid this is going to be a horrendous fire, but the fire professionals who will be conducting this burn assure me there is very little to worry about,” Haggstrom said. “Fuel to carry the fire is scant in the subalpine, it’s mostly grass, leaves and twigs.”

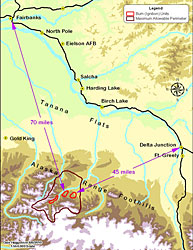

Haggstrom is the fire and habitat management coordinator for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He and his colleague, biologist Tom Paragi, collaborated with fire specialists in the Alaska Division of Forestry to plan the burn 70 miles southeast of Fairbanks at the headwaters of the Little Delta River drainage.

The biologists explained how wildland fire is good for moose, why these moose need this fire, and why this unusual prescribed burn has the attention of Interior foresters. It’s part habitat enhancement, part experiment in whether firing will be successful in this fuel type. And it may not even happen: Paragi said a half-dozen factors can derail a prescribed burn.

Narrow Window and an Unusual Burn

Planners are looking at a narrow window after the snow is gone and the ground litter has dried enough to burn and before the vegetation greens up and won’t readily burn. If conditions permit it will happen sometime between May 1 and June 15, ideally in the third week of May.

Paragi has marked out three areas for the burn, each about 2,000 acres. He figures only about a fourth of that total, 1,500 acres, is likely to burn. The treatment area is between 3,000 and 3,500 feet in elevation, which is unusual.

“The three areas are three habitat types in the subalpine area,” Paragi said. “We’re looking at all of them as a treatment area. We’ve never done this in the alpine before, just down in the spruce dominated forest.”

Part of the experiment is to see if prescribed fire can even work as a tool to rejuvenate willows at that elevation. Will it burn? Fire is a natural part of the ecology of the boreal forest, but it’s unusual in the alpine.

“At lower elevations dry lightning is apparently more common – with no associated rain storms – and there is a much better chance of a fire actually starting and spreading,” Paragi said. “Fire disturbance is much less frequent up there than in the boreal forest. There is fair amount of lightning up there, but fire colleagues tell me it’s more often associated with rain.”

The Alaska Division of Forestry will conduct the burn and protect any cabins or mining claims.

“We set up the projects and pay for them, Forestry does the burning,” said Haggstrom. “They have the training and experience to do it safely.”

Marc Lee is the area forester with the Department of Forestry. He’s interested to see if fire can even be used as a habitat enhancement tool in the subalpine. “It’s an area that rarely gets any fire,” he said. “Fire in the alpine doesn’t tend to go very far.”

Burning For the Moose

The treatment area is in Game Management Unit 20A and is prime habitat for moose in fall and early winter. The broomed condition of the willow shows it’s been heavily browsed for many years. Haggstrom said moose in 20A are showing signs of habitat stress; they’re having calves at an older age, the calves are lighter weight, and there are fewer twins. If spring burning can produce more willow and can be done cost-effectively over a large area, it will help managers maintain current numbers of moose.

“We know when you burn willow in the spring, when the soil is moist and the roots are protected, you’re only top-killing them, so new stems sprout from the roots,” Haggstrom said. “Willow gets lots more stems, and in response grows more than you started with. In some willow species the older ones can be so tall moose can’t reach the top. The new stems are down where a moose can reach them. You get an increase in biomass, more stems and leaves; you also get an improvement in quality of the forage the first couple years. That lush growth is like candy to the moose. They really pack in because it’s so nutritious and tender. In subsequent years you still have the increase in quantity but the nutritional quality returns to normal.”

Habitat managers also crush vegetation to get the same effect. Just as willow and alder respond to wildland fire by sprouting new shoot or “suckers,” the plants also respond to damage caused by seasonal flooding and ice-scouring. In a big treatment area, if you can light a fire it’s far cheaper than a using a bulldozer.

Checks and Balances Dictate Burn Feasibility

“The history of prescribed burns is mostly one of no go’s,” said Paragi. “Many burns are planned, and it often takes years to get all the contingencies to fall into place.”

Paragi and Haggstrom planned some prescribed burns on the Tanana Flats south of Fairbanks in the mid 1990s that still have not happened. For those burns, in older spruce forest with a thick organic soil layer, the area has to be dry enough for the fire to consume the organics and expose the mineral soil for willow seeds, but not so dry it could be a hazard to keep within the desired boundaries. That creates a narrow window of opportunity. Firefighting crews have to be available and standing by in case they are needed, and if they are busy elsewhere the prescribed burn can’t happen. Factor in rain, wind direction, and any military operations in the area with airspace concerns.

“There are lots of checks and balances,” Paragi said. “All these things are on the checklist and any one can be a showstopper.”

A 43-page Prescribed Burn Plan outlines the details of the burn. This burn was planned for last spring, but several of these factors “ran out the clock” on the prescription window.

Forestry fire personnel carefully burned about three-quarters of an acre in the area in 2008 as a test in subalpine fuels at 2,600 foot elevation.

“We did a small test burn about 15 miles away to get the fire crews up there so they could get a feel for the type of burn needed,” Paragi said. “It was instructive. Anytime they do a burn they do a test burn first – set a small fire by hand that they can control and see if it behaves as expected.”

One concern about this burn is katabatic wind – cold air rushing down from the glaciers, which could really hamper the potential spread or push it outside the intended burn area.

“The fear is that the fire could just peter out,” Paragi said. “We want it to go up(slope) and if you have downslope winds it’s a no go condition.”

A potential problem with the fire burning upslope is that it could burn too quickly and without much intensity, flashing across the top. Planners hope to increase the “residence time” of the the fire.

“The challenge is to get enough fire to do some good – enough to scorch the willows.” Haggstrom said. “If they simply light it at the bottom of the hill it’s likely to run rapidly up the slope without lingering in any one place long enough to produce the heat necessary to top-kill the willows. They’ll strip burn it, igniting it from the top down in sections that run along the contour. This slows the rate of spread to keep the heat around the base of the willows a little longer.”

Setting the Fire

Sometimes prescribed burns are set on the ground by crews afoot; others are set dramatically by a helicopter essentially using a big drip torch. This prescribed burn is to be set from the air, but will be using a different tool, an aerial firing device known in the trade as a ping pong machine.

“These little spheres contain a chemical that is stable by itself,” Haggstrom said. “The machine spits them out like a batting practice ball thrower, and as each one comes out another chemical is injected into the sphere. The two react to produce a fire where the sphere lands on the ground. Each fire spreads into the surrounding vegetation.”

It works quite well under the right conditions and is cheaper than using a torch with jellied gasoline, Haggstrom said. The plan is to burn all three areas on the same day.

The second part of the research will be to compare the response of the vegetation to burning in each of the three areas. Biologists want to learn how quickly the different hardwoods and willows grow to a height above the average snow depth for moose forage. Browse plots done in March 2009 will provide the baseline for comparison measurements after the fire to see if stem density and browse biomass (pounds per acre) in subalpine areas increases as rapidly as it does in low-severity burns in boreal forest.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.