Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

January 2010

Where Sleeping Bears Lie

Joe Baxter was climbing a ridge on a hunting trip when he found himself face to face with a bedded down but wide awake black bear.

It was October, and the Juneau hunter and outdoorsman was hoping to bag a mountain goat on an archery-only hunt. He was picking his way through a set of cliffs to access the alpine when he heard a snort and looked up to see a bear lying in a hole amid the roots of a big spruce.

“Here is this bear calmly staring at me, about five feet away,” Baxter said. “He was probably asleep and I startled him. The only thing poking out of his den was his head, and because of the angle I was looking face to face.”

Across Alaska, thousands of bears are asleep in their winter dens. Because black bears are relatively tolerant of people – and many Alaska communities are in prime black bear habitat - some of these dens are almost underfoot.

“You can run into a bear den just about anywhere,” said state wildlife biologist Ryan Scott, who has worked with Juneau bears for years. Black bear dens in particular can be in all habitats and locations, although the ideal den is on a north facing slope, protected from weather in an area with well-drained soil. Keeping dry is critical, and bears will abandon a soggy den.

Dens provide winter shelter for hibernating bears and are not year-round homes, contrary to the cartoonish image of a cave – the entrance littered with bones – that’s often portrayed. Roots, rock crevices, hollow trees and even buildings provide shelter for hibernating bears. Sometimes the den is not much larger than the bear, and sometimes the opening is quite small.

“They’re all different,” Scott said. “There’s a bear den about 800 feet up behind Juneau in a hollowed-out standing cottonwood tree. We think the bear climbed up the tree and then back down inside it. There’s a little opening at the bottom she might be able squeeze out through in the spring.”

Scott has received calls from local homeowners who have discovered bears hibernating under their porches. “Under porches, sheds and decks, right here in town,” he said. Site preparation work in suburban Juneau – the Mendenhall Valley – has uncovered bears sleeping in dens in vacant lots amid neighborhoods.

About a dozen black bears delight summer visitors to the Mendenhall Glacier as they catch salmon below viewing platforms crowded with tourists. Although two dens have been found near the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center, just a stone’s throw from the lakeshore, Forest Service biologist Dennis Chester suspects most of those bears den in the hillsides above the valley, targeting spots that keep them dry. Naturalist Laurie Ferguson Craig said she knows that one of the bears, a 21-year-old female who wore a GPS collar for a few years, denned up in Nugget Creek Basin several miles from the center.

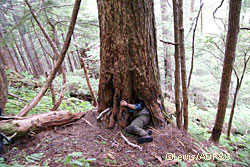

She and Chester both noted that the root masses of trees that start their lives on nurse trees make particularly good den sites. These “bowlegged” trees grow on fallen logs and stumps, and as the dead nurse tree rots, a space is created in the stilt-like roots of the growing tree.

Retired state biologist John Hechtel began studying bears in 1977 and worked with radio-collared bears in Interior Alaska and the Yukon for most of 25 years. Radio collars allow researchers to locate hibernating bears in their dens, and Hechtel said finding those dens was amazing.

“A lot of times you couldn't even tell a den was there,” he said. “It makes you wonder what you've walked by. Scattered through the landscape under the snow these bears are tucked away – and you'd never know.”

Sometimes bears will drag spruce boughs or grass into the den to make a bed, Hechtel said, sometimes not. In the dry Interior he’s found bears that didn’t even use a den - sometimes a bear will just lie down on the dirt and let the snow cover it. He once found a nest-like den where bears mounded up a huge pile of grass, shaped like a big beaver lodge, and burrowed inside.

“There were four bears in there – a mother bear with three, two-year-old cubs,” he said.

Brown bears dens somewhat different

Brown bears, less tolerant of people than black bears, are not encountered in their dens very often. That’s a good thing – unlike black bears, they are notoriously ill-tempered when disturbed in winter.

Fish and Game bear researcher LaVern Beier has worked with bears since the 1970s, including a research project specifically looking at bear dens on Admiralty Island. While the basic requirements for shelter are the same, there is tremendous variety depending on the area.

“Bear dens are different from location to location,” he said. “It’s based on habitat. The Unuk River, Berners Bay, Admiralty Island are all different because the landscape and habitat are different. On Admiralty, a big part of (bears’) life is up high in the alpine. In the Berners area, the bears rarely go over 1,000 feet. The den elevations are much, much lower, more in the forest.”

The average elevation of Admiralty dens is 2,000 feet, he said, and he found one that was much higher, near the summit of Eagle Peak, the highest point on the island. “Some of those dens were buried under as much as 14-feet of snow in the winter,” he said.

Bears in Southeast tend to hibernate in dens they find, while bears in the Interior and on Kodiak Island tend to excavate dens, Beier said. He attributes that to the wet climate of Southeast.

“An excavated den on Admiralty is very rare,” he said. “They may do a little bit of excavation just to make it more comfortable.”

Admiralty dens tend to be in natural rock cavities or under the roots of very large, standing trees.

Beier said the average home range of Admiralty male bears is about 40 square miles, and just 12 square miles for females. Those are home ranges, not territories, and they overlap with other bears. A female might be born, live her entire life and die in that small home range. Bears become extremely intimate with their surroundings, Beier said. “They learn where the good den sites are, and when it’s time to bed down, they remember. But maybe somebody else is already there.”

“There’s a high density of bears, there are only so many den sites out there, and everyone knows where they are,” he said. The dens are used year after year, but not necessarily by the same bear. “I followed one bear for 13 years and he only used the same den two times, and it wasn’t two years in a row.”

Dens are used by generations of bears, and some may have been used for thousands of years. Beier has been inside dens where the rocks are rubbed smooth by the passage of bears. The dens are usually very clean inside, as the bears don’t urinate or defecate in the dens during hibernation. Often you had to look hard just to find a hair, he said.

“Some bears would drag in vegetation, others just curl up,” he said. “Sows with cubs generally make a nest.”

Riley Woodford is a writer for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He edits the online magazine, Alaska Fish and Wildlife News, (wildlifenews.alaska.gov) and produces the Sounds Wild radio program.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.