Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

May 2025

Shrimping in Southeast Alaska

Personal Use Trawling

My parents gave me some good advice growing up in Appalachia. When I was considering moving to Alaska to attend college (and find the fishing I’d seen on the Virgil Ward show) I was nervous, as I’d never known anyone to move this far away for college, or anything else for that matter, unless it was in the military. My dad said, “What are you worried about? You can always come home.” A couple years later, when I was about 21 and pondering whether to spend money to fly home (my first time in a plane) for a family function, my mother advised, “What’s to decide? You can always make money.” That sage advice led to many good decisions that boiled down to a single mantra: always say yes when opportunity knocks. When someone says, “Hey - we’re going deer hunting (or fishing or trapping or shrimping) - you want to go?” If the first word out of your mouth is “YES,” you’ll be a happy camper. You can’t buy time. On your deathbed, you won’t be thinking, dang, I wish I’d spent more time at the office. Saying yes not only gets you more outdoor experience and skills, YOU start to be the go-to person who gets the call the next time someone is inviting. People that say “no” more than once usually get checked off the list, and even if you are a neophyte, willingness to go outweighs your inexperience.

Such was the case when I got invited to go shrimp trawling in Southeast Alaska with my friend Mike. He asked, “You wanna go shrimping tomorrow?” My answer was, “What time do we leave?” Next day I found myself on another trip of a lifetime. On our way to his favorite shrimping spot, he stopped to toss an offering of dried halibut at the grave of a shaman located on a nondescript island. The gravesite, guarded by two carved totem warriors, was hidden along the shore. The site must be over a hundred years old, and you have to know exactly where it’s at in the wilderness, as it’s not readily visible from the water (I’m thankful no government agencies have disturbed or advertised it yet, to my knowledge). I’ve lived in Alaska since I was a teenager, and this was one of the most remarkable experiences I’ve had (NOTE to reader: You won’t see stuff like this in the office….). I pass by the spot a couple times a year now, and drift for a short while to pay my respects and think about what life was like for that shaman not all that long ago.

Personal use shrimping is allowed by three methods in Southeast Alaska - by ring net, pot and trawl. Pot gear primarily targets spot and coonstripe shrimp in mud, sand and rocky habitats. Trawls generally target sidestripe, coonstripe and pink shrimp on mud and sand bottoms in depths from 50 feet down to 250 feet or more. Ring nets could be used in most any habitat.

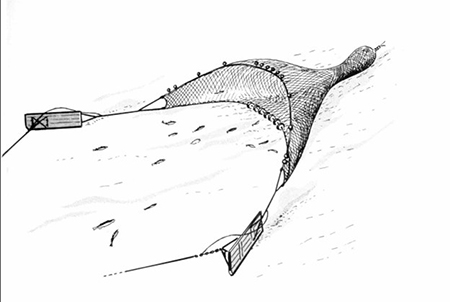

Two types of shrimp trawls are allowed for personal use fishing - otter trawls and beam trawls. Beam trawls use a horizontal bar to keep the mouth of a cone-shaped net open.

Otter trawls, which is what we fished, use “otter doors,” which are weighted boards tied by a line to each side of the mouth of a conical net. The doors pull at an angle to the boat and keep the wings of the net open. A bridle line from each door leads forward, where the two lines meet at a swivel with an eye on either end. The bridle line ends are joined together at one swivel eye and the towline is attached to the other swivel eye. A 10-pound cannonball weight is also snapped in at the eye with the bridle lines. Memphis Net and Twine Company is the go-to store to order these nets. I don’t know anyone who has ordered from anywhere else.

To fish the trawl, find a relatively flat bottom of mud or sand. Many times these may be at the mouth of a river or creek or off a glacier. And, as I’ve subsequently learned, the best information you can have about a spot is that people have caught shrimp there before. I, and others in this article have tried many similar spots of comparable depth and bottom type, but don’t find shrimp. Some spots hold shrimp and others don’t.

Fishing the Trawl

When we got to Mike’s favorite spot, it was nondescript in most every way - just a stretch of water between islands. He ran the course we’d fish first and watched his sounder for obstacles. Then, he made sure the cod end of the net (the back) was tied shut. He readied his net, lined the boat up on his course, and put the boat in gear at idle speed. He fed the cod end of the net into the water and paid out the rest of the net. Next, he dumped in the otter boards. He handed me the bridle line to the board on my side of the stern, while he held the bridle line of the other board on his side of the stern. Together, we slowly fed out the otter boards from either side of the stern and made sure the net was open and fishing properly - with the floats on top of the net mouth, and the chain on the bottom, and no twists in the lines anywhere. When it all looked good back there, we paid out the bridles until they joined at the swivel and Mike started paying out a short run of the towline as the net went out of sight. He handed me the towline and had me pay it out under a little tension while he drove his course and watched the sounder for depth and obstacles.

A rule of thumb is you need about 3 to 4 times the length of towline as the depth you are fishing. So, if you’re fishing the net in 100 feet of water, you need 300 to 400 feet of towline to get the net on bottom. Usually, when you let the line out in this range and tie it off while towing at a forward idle speed, you will see the boat speed drop, and then steady to a slower speed. Our speed ranged from 1.3 to 1.7 knots, depending on the depth we’re fishing. The size and power of the boat is also a factor in your speed.

Once the towline is paid out to the 3 to 4:1 distance, the line should be tied off to a cleat or other solid structure, and a person should tend the line in case it needs to be released quickly. The person at the helm needs to pay attention to the depth and to the bottom, in case there’s an abrupt change, such as a pinnacle or obvious tree on the bottom. Luckily, when you see the obstacle, there’s plenty of time to avoid it by simply stopping and hauling the net back in, as the obstacle is under the boat, while the net is back there a football field or more.

I would not recommend fishing a trawl alone. One or two people are needed to deploy the net. Once the net is deployed, it’s good to have one person tending the towline while one person is steering the boat and watching the bottom on the depth sounder.

It can be hard at times to tell if you are moving or not. I’ve been fooled thinking I was moving forward, when actually my net was snagged on bottom and I was arching toward the bank or to the deep. Other times, I noticed that the boat speed went to zero, or that I’d stopped moving in relation to the shoreline. When this happens, it’s time to stop and haul back the line and hope the net frees up from the bottom. It usually does.

I tow for about 30 minutes to an hour, depending on the distance of fishable bottom and prior experience if I’ve fished the area before.

From my experience, either you find a spot that works and you get several gallons worth of the shrimp in the haul, or you get next to nothing (including nothing!) When you find them, you find them.

Depending on where you fish, you might get pinks or side stripes or coonstripes. Rarely do we get spot shrimp. When we do catch shrimp, it seems like we always get at least some pinks. Sometimes they are the dominant species in the net. Other times, they may be second to coonstripes or side stripes. I don’t remember catching both coonstripes and side stripes in the same place - usually it’s one or the other. Also, sometimes the shrimp species vary by depth, with one species in shallower, and the other deeper. And it’s not always the same species that’s in shallower and the other deeper. Every day may be different.

While we were towing, Mike got baskets, five-gallon buckets, and totes situated on the deck. When it was time to haul in the net, we turned the boat back the way we came, and I idled the boat back towards the net, trying to just keep up with the slack in the towline as Mike tended and coiled the towline through the line hauler. We hauled back the towline to the bridle swivel, then I put the boat in neutral. We each grabbed a bridle line and pulled in unison until we got the otter boards on board, then labored on the lines the remaining distance until the top of the net surfaced.

Hauling the net contents aboard depends on how much you have, and again, it’s always good to have at least two people. If the net is full, you may need to brailer (transfer) shrimp out of it little by little into the boat until the net is light enough to roll it over the side and on board. When you get the net on board, put the cod end into a sorting tote, untie the cod end, and shake the contents into the tote. From here, separate the shrimp from whatever else is in the net. Non-shrimp critters like fish and crab are sent over the side. You’ll see lots of neat fish you’d only see in books, like gobies and lumpsuckers and small flatfishes and little sculpins - fish with mouths so small you’d never catch them on a hook, and so small you’d rarely see them in a gill or seine net. The shrimp trawl nets have small mesh, so fish don’t gill themselves and get injured and we release them back to the water after a quick look.

The catch can range from nearly all shrimp to no shrimp and everything in between. Having a hose or spare bucket you can use to scoop seawater and rinse the mud off the catch is a big help. Have a stack of five-gallon buckets to sort the shrimp. If you find the shrimp honey hole, you’re going to need numerous buckets or a good-sized cooler to hold the catch. You’ll want to have ice on hand, too, in warmer weather (40 degrees F or higher) to maintain shrimp quality until you get them processed and into refrigeration or a freezer.

Note: A personal use permit is required for shrimping like this and can be obtained at your local Fish and Game office. 2024–2025 Subsistence and Personal Use Statewide Fishing Regulations

Gaining Experience

Fast forward to a couple winters later. Word got to me that a couple guys trapping furbearers on islands near Juneau needed a boat ride out to check their traps until their boat was repaired. “Sure,” I said, “I’d take them.” I hadn’t trapped furbearers myself in several years and was eager just to get out on the water in the dead of winter. I mentioned to Nick, one of the trappers, that I’d bought a trawl net on Craigslist after fishing with Mike, and I wanted to relearn how to fish it. Nick said he just happened to be a shrimp trawler and would be happy to take me in the spring. (See how this saying “yes” thing works?)

A few months later, Nick took me out in his boat with his deer hunting partner, Amanda, to show me how they fished Nick’s shrimp trawl from his boat. We caught lots of shrimp - again, mostly pink shrimp. The next outing Nick and Amanda went with me. This was my first turn to set my own net from my own boat. Nick set the net with me while Amanda drove the boat. Not long after we set the net, we snagged it on the bottom and lost it! I’d seen Mike and Nick both hang the bottom with their nets and the nets came right out once we got the boat directly over the hung net. My net would not come loose, and the towline parted when we pulled. I’m guessing my net was hung in the root wad of a sunken tree, as we were fishing the same location where Nick had taken me a few months before and we had not encountered any obstacles.

Lucky for me, Amanda knew a guy. He was looking to sell his net and I bought it over the phone before we got back to the dock. When I showed up to buy the net it turned out I knew the guy too. We used to work together. Life in a small town.

This was a smaller 8-foot net, with smaller otter doors than the 12-foot nets Mike and Nick fished. I have to say I sure like the smaller net, since I can set the net by myself while I have my crew drive the boat. I’ve fished the smaller net several times now and it fishes well. The doors are lighter and much less cumbersome than the doors on the 12-foot nets. The net may catch less per haul than the bigger nets but it’s easier to bring back aboard.

Sometimes you get a lot of pink shrimp out trawling. And sometimes those pink shrimp are big enough where it's easy to take the head off and remove the shell from the tail. You can use these shrimp in most any recipe you can find online or in a book. But sometimes you get really small pink shrimp. The kind that you have to be real careful not to squish when you take off the shell - if you can take the shell off at all.

So, I started looking for ways to eat these small shrimp - shell and all. My wife Sara tried coating them in Panko and frying them, which was okay, but not great. And messy. Next, I saw a recipe that just fried the snot out of whole shrimp in olive oil. I didn't like that too much. The texture was okay, but I didn't like the (perhaps) overheated olive oil taste.

What's a shrimper to do? There were bags and bags of little raw pink shrimp staring me in the face every time I opened the freezer. If I could come up with an easy way to use them then catching them in the trawl the next time wouldn’t feel like such a chore as to what to do with them.

Then I remembered how I’d seen ceviche made in Ecuador when I was working there with coastal small boat fishermen as a volunteer for the US Farmer to Farmer program a few years ago. The daughter of the host fisherman showed me how they make ceviche. She shelled the prawns her dad caught like we would, but she kept the shells. She minced them finely in a blender with various citrus juices and other ingredients for the ceviche liquid. You’d never know the shells were in the liquid if you didn’t see it made, and of course, the dish was as good as ceviche gets.

Remembering that I decided to try to make shrimp cakes. I had a bag of frozen raw tiny tails with the shell on. I put the partially thawed tails into the blender and let it whirl. I blended until the shrimp was a thick paste - like the texture of soft serve ice cream.

Now I needed binders. After experimenting with various ingredients, I settled on eggs, fine almond flour, finely grated parmesan cheese, finely chopped yellow onion, and coarsely cut cherry peppers stuffed with cream cheese. The almond flour didn’t do much for binding, I found out, but did add nice flavor. I’m sure bread crumbs or all-purpose flour would work well, too. The best frying mediums were avocado oil or West African palm oil.

The ingredients worked well together, held together nicely as a patty, and a topping of kelp relish with mayonnaise with a little Sriracha sauce made a good thing even better. Sara ate three of the four patties I made, fresh out of the pan, confirming I was on to something. Shrimp cakes are here to stay.

Mark Stopha is a Juneau outdoorsman, writer, and former ADF&G fishery biologist and commercial fisherman. He co-owns the Alaska Wild Salmon Company. He has previously written about fishing, hunting, trapping, salmon hatcheries and research, and the especially good caring for your catch for Alaska Fish and Wildlife News.

More articles by Mark Stopha

Alaska Kelp Farming: The Blue Revolution

Grouse hunting - The Hooter Obsession

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.