Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

January 2025

Stalking Shorebirds on Alaska’s Remote Outer Coast

Researching Elusive Red Knots Part 1

Aaron looked like some sort of dragonfly, or maybe an early Wright Brother experiment. The packraft was tethered to the back of his bike and the paddles strapped to his back stuck out like insect wings on either side. Every so often the wind caught the paddle blades, and he shifted slightly off course. I was just aft of him, biking slowly over the intertidal mud and sand. The lopsided tripod and spotting scope were strapped to my handlebars with bright orange and blue ski straps and the shotgun was slung across my chest, a constant bobbing reminder that out here we were somewhere in the middle of the food chain. It was 2022, the first year of my Red Knot project in Controller Bay, Alaska, and so far after nearly two years of planning we still had a lot to learn about bears, birds, bikes and working in this remote bay.

I developed this project when I was first hired by the Alaska Department of Fish & Game as the Endangered Species Biologist in 2020. It was Covid times, and I spent most of that year working from a sturdy oak desk in the corner of a 700 square foot apartment above a garage that my husband, our husky and new labrador puppy occupied in Juneau. My directives for developing a project were simple. I was to select a Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), develop a research question, collaborate with partners that could support the work, plan for a three-year funded project, and pitch it to our team of senior biologists for review. As a freshly minted PhD these guidelines felt limitless. The list of SGCN species was long and because I was in a statewide position, my project could be based out of any region or in any ecosystem. But it was an odd time to develop a project. Ideas that were formerly developed in office settings, in-person meetings and over coffee breaks at conferences were discussed over Zoom and Teams calls and in long email chains.

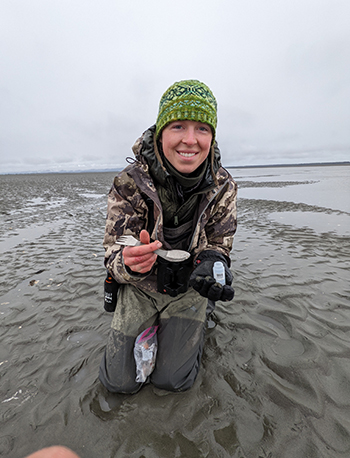

I decided to study Pacific Red Knots, a declining species of sandpiper that overwinters in Mexico and breeds in Alaska and Russia. My reasons were straightforward. They are in steep decline according to multiple conservation lists and rankings, they inhabit the marine ecosystem, which was my area of expertise (my previous research included marine mammal, and fisheries work in Alaska), and I like birds. I collaborated with Erin Cooper, above right, the Program Manager of the Chugach National Forest Wildlife, Ecology and Vegetation Management Program for the US Forest Service, to develop a site-specific study to determine the number of Pacific Red Knots stopping in Controller Bay during their spring migration.

I decided to study Pacific Red Knots, a declining species of sandpiper that overwinters in Mexico and breeds in Alaska and Russia. My reasons were straightforward. They are in steep decline according to multiple conservation lists and rankings, they inhabit the marine ecosystem, which was my area of expertise (my previous research included marine mammal, and fisheries work in Alaska), and I like birds. I collaborated with Erin Cooper, above right, the Program Manager of the Chugach National Forest Wildlife, Ecology and Vegetation Management Program for the US Forest Service, to develop a site-specific study to determine the number of Pacific Red Knots stopping in Controller Bay during their spring migration.

Controller Bay is on a lonely stretch of coastline east of Prince William Sound, 60 miles from the remote community of Cordova, which is not connected to Alaska’s road system. The Steller and Bering glaciers (the Bering is the largest glacier in North America), loom over the bay in the backdrop and the meltwaters of the Steller Glacier flow into the bay. We already knew Controller Bay was an important location for some Pacific Red Knots, thanks to telemetry work done by other biologists in Alaska. They tagged knots in Washington state with tracking devices and then later flew along Alaska’s Outer Coast, identifying key stopover sites. Stopover sites for migratory shorebirds are places where the birds rest during their long migration and fuel up on rich feeding grounds. For shorebirds, these locations are critical to their survival. Pacific Red Knots can cover 3,000 miles in a single flight, flying both day and night for two days straight. However, there are large energetic costs to such a feat. The birds burn stored fat to see them through until they find a safe pit stop to forage and rest until continuing on to their breeding grounds further north. While the telemetry study identified  Controller Bay as one of these important stopover sites for some knots, it really opened the door to more questions. Specifically, I was interested in determining how many Red Knots are relying on this one small bay, and what are they eating there that makes this location worth visiting?

Controller Bay as one of these important stopover sites for some knots, it really opened the door to more questions. Specifically, I was interested in determining how many Red Knots are relying on this one small bay, and what are they eating there that makes this location worth visiting?

Why Red Knots?

Red Knots are a cosmopolitan species that can be found on every continent except Antarctica. Pacific Red Knots are one of the six recognized subspecies across the globe. A good deal of research has been done on the rufa, or Atlantic subspecies on the East coast of the US. These birds are famous for foraging on horseshoe crab eggs in Delaware Bay and are currently listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

One of the duties of my job as a biologist with ADF&G’s Threatened, Endangered and Diversity (TED) Program is to conduct research on declining species. If we can better understand the extent of declines, threats to the population, and fill in vital knowledge gaps regarding the ecology of these species, we can work on conservation actions before they need to be listed under the ESA. While rufa Red Knots have received a good deal of scientific study and media attention, much less is known about their Pacific cousins.

Using the rufa subspecies as a model, I dug into the literature and learned that most abundance estimates for those Atlantic Red Knots were conducted by aerial surveys. This was done on the East Coast of the US and in their overwintering range in South America. I set out to replicate these methods and designed a project involving an aerial survey approach that would occur for about a month in Controller Bay. The goal was to learn - what percent of the population relies on Controller Bay as a key stopover site? I budgeted money to fund the flights needed, to hire a technician to help me do the work, to buy one camera and lens, and some travel to and from Cordova, the nearest town to Controller Bay.

Using the rufa subspecies as a model, I dug into the literature and learned that most abundance estimates for those Atlantic Red Knots were conducted by aerial surveys. This was done on the East Coast of the US and in their overwintering range in South America. I set out to replicate these methods and designed a project involving an aerial survey approach that would occur for about a month in Controller Bay. The goal was to learn - what percent of the population relies on Controller Bay as a key stopover site? I budgeted money to fund the flights needed, to hire a technician to help me do the work, to buy one camera and lens, and some travel to and from Cordova, the nearest town to Controller Bay.

My project was approved and funded in 2021. I scraped together funds for a reconnaissance mission prior to the season start date in 2022. I wanted to scout the study site, do a trial run with the aerial survey and spend a few days camping out in the bay familiarizing myself with my new study species and their behavior.

The aerial survey methods would employ two observers: one photographer to take shots of flocks of the birds and one note taker to run software recording the survey route and to record oral abundance estimates. The digital images would be reviewed later in the office and the birds counted electronically. The software and photography methods were already established by the ADF&G waterfowl program and used widely across Alaska.

The aerial survey methods would employ two observers: one photographer to take shots of flocks of the birds and one note taker to run software recording the survey route and to record oral abundance estimates. The digital images would be reviewed later in the office and the birds counted electronically. The software and photography methods were already established by the ADF&G waterfowl program and used widely across Alaska.

High winds on the mudflats

What we learned turned out to be pivotal: Controller Bay is a poor place to conduct aerial survey work. First, this part of the state has a much lower tidal range than Southeast. Although the bay experiences a 13-foot tide once in a great while, most of the tides in this area are around 7-8 feet. This meant that even when conducting a high tide survey, much of the mudflat was exposed, creating a lot of habitat for foraging shorebirds and a lot of topography to cover. The Bay itself is a “C” shape and the irregular exposure of sand and mud meant that birds could spread out. It put them on both sides of the plane, and the photographer could only capture the birds on one side. Additionally, high winds in the area  meant that you might be flying nice and slow when surveying into the wind, but if you had a tailwind, there was no way to slow down. So even if you could do a double pass to get counts on both sides of the plane and the birds didn’t flush (which they always did), wind direction would determine the survey speed and it was going to be highly variable. Additionally, I learned from the pilot, Captain Steve, that the weather getting to/from Cordova to the bay was often poor and there were likely to be regular flight cancelations. Lastly, and most importantly, we learned that the Pacific Red Knots rarely grouped up in large homogenous flocks like their rufa cousins.

meant that you might be flying nice and slow when surveying into the wind, but if you had a tailwind, there was no way to slow down. So even if you could do a double pass to get counts on both sides of the plane and the birds didn’t flush (which they always did), wind direction would determine the survey speed and it was going to be highly variable. Additionally, I learned from the pilot, Captain Steve, that the weather getting to/from Cordova to the bay was often poor and there were likely to be regular flight cancelations. Lastly, and most importantly, we learned that the Pacific Red Knots rarely grouped up in large homogenous flocks like their rufa cousins.

From the ground, Red Knots are distinctive. They are about the size of a robin, they have a medium-length bill for a shorebird that ever so slightly droops downward, but really what’s so eye catching about this sandpiper is their breeding plumage. Whereas most shorebirds are variations of white, brown, black and rust, Red Knots are  terracotta orange from their heads to their bellies in spring and summer. They have tiny grey feathers that adorn the tops of their heads and form a stripe running from their bill to behind their eye. When the sunlight shines on a flock roosting at the water’s edge, they look like the sunset sinking into the Pacific. This is all lovely for bird watchers, but from the air they are nearly identical in size and dorsal coloration to both short and long-billed dowitchers - which are abundant in large numbers in the bay during spring migration. After a single test survey, I quickly realized that this method was not going to work in Controller Bay, Alaska. I was going to have to completely revamp the project if I was going to have any success.

terracotta orange from their heads to their bellies in spring and summer. They have tiny grey feathers that adorn the tops of their heads and form a stripe running from their bill to behind their eye. When the sunlight shines on a flock roosting at the water’s edge, they look like the sunset sinking into the Pacific. This is all lovely for bird watchers, but from the air they are nearly identical in size and dorsal coloration to both short and long-billed dowitchers - which are abundant in large numbers in the bay during spring migration. After a single test survey, I quickly realized that this method was not going to work in Controller Bay, Alaska. I was going to have to completely revamp the project if I was going to have any success.

A promising recon

My four-day camping trip in Controller Bay proved more fruitful. My collaborator, Erin, had been to the bay a few times recreating and birding and knew there was an ideal place to land and camp along the inside of Okalee Spit, the peninsula of mainland that juts out towards Kayak Island. She had this location on her radar for some time due to its importance for both shorebirds and waterfowl. She even sent some of her staff out to survey the bay for shorebirds on bikes; the report was that it was difficult but doable. With that knowledge, I poked my head into the local bike shop to inquire about rentals. “Oh cool, yes you’d want the fat tire bikes! You can definitely bike out there. That’s going to be amazing, can I join you?” Natasha, the store owner joked with me. I was somewhat amazed that she was letting me use their rental bikes along the saltwater coast, but I gave her full disclosure on the activities!

So, we packed some tents, the rental bikes, a cooler of food and a bear fence and Erin, myself and one lucky volunteer loaded up in the de Havilland beaver, a workhorse airplane popular in coastal Alaska. “It’s big country out there,” Captain Steve said as he played Tetris to make the clunky frames and tires fit inside. I didn’t really know what he meant but I knew where I was going. The spit we would be camping on was adjacent to Kayak Island. A famous landmark, it was the first place Vitus Bering landed when he “discovered” Alaska in 1741. German physician Georg Wilhelm Steller, for whom Steller Sea Lions, Steller’s Jay, Steller’s Eider and Steller Sea Cows are named, explored Kayak for just a few hours before Bering and his crew departed. Captain Cook named the bay in 1778 but did not land. While the area was already home to the Eyak people, it did not see visitors again until the discovery of oil in the early 1900s, when Controller Bay became Alaska’s first oil field. Katalla, a nearby boom town, was

So, we packed some tents, the rental bikes, a cooler of food and a bear fence and Erin, myself and one lucky volunteer loaded up in the de Havilland beaver, a workhorse airplane popular in coastal Alaska. “It’s big country out there,” Captain Steve said as he played Tetris to make the clunky frames and tires fit inside. I didn’t really know what he meant but I knew where I was going. The spit we would be camping on was adjacent to Kayak Island. A famous landmark, it was the first place Vitus Bering landed when he “discovered” Alaska in 1741. German physician Georg Wilhelm Steller, for whom Steller Sea Lions, Steller’s Jay, Steller’s Eider and Steller Sea Cows are named, explored Kayak for just a few hours before Bering and his crew departed. Captain Cook named the bay in 1778 but did not land. While the area was already home to the Eyak people, it did not see visitors again until the discovery of oil in the early 1900s, when Controller Bay became Alaska’s first oil field. Katalla, a nearby boom town, was  developed in 1910 and a railway was established to bring goods and people in and out. Coal was pulled out of the Bering River Coal Fields. The Bering River feeds the north end of the bay with water from the Steller Glacier and swells dramatically during the spring melt. Katalla was abandoned some 30 years later. Now from the air all you can make out of its existence are some old pilings jutting out in a symmetrical line into the ocean. These days, hunters and fishermen in search of moose, black or brown bears, and coho salmon are some of the only visitors to this historic bit of coastline.

developed in 1910 and a railway was established to bring goods and people in and out. Coal was pulled out of the Bering River Coal Fields. The Bering River feeds the north end of the bay with water from the Steller Glacier and swells dramatically during the spring melt. Katalla was abandoned some 30 years later. Now from the air all you can make out of its existence are some old pilings jutting out in a symmetrical line into the ocean. These days, hunters and fishermen in search of moose, black or brown bears, and coho salmon are some of the only visitors to this historic bit of coastline.

The bay itself is shallow and protected from the open ocean by the low lying Kanak island. During low tides, the shallow waters are pulled out to the Gulf of Alaska and the mudflats are so expansive that it appears you could walk the 4.5 miles from the mainland all the way out to Wingham Island. In our four days out there, we had interactions with coyotes that yipped at us in alert, a curious porcupine that had probably never seen a human before and set up shop on the only tree at the end of the spit, and I even saw a moose strolling cautiously along the sandy beach 20 feet from our tents, probably scoping out a safe place to give birth to her calf.

Our volunteer, my husband Mattheus, and I took the bikes down the coastline to see how much ground we could cover when we came across some good-sized brown bear tracks. Where else on earth can you watch a moose stroll on a sandy beach without any timber nearby, where do coyotes yips overlay wolf howls, and black and brown bears coexist with regularity? Not only that, but from Okalee Spit you could see the Steller Glacier, rising out of the ground and looming over the north end of the bay like an icy throne, pushing glacial silt and freshwater into the Pacific. And if that wasn’t enough, the highest coastal mountain range in the world forms the eastern backdrop to the bay. On clear days you could see Mount Saint Elias (the second tallest mountain in North America) rising 18,000 ft into the atmosphere in its snow laden glory. The Wrangel Mountain Range feels so close that you might be able to walk there in two days’ time but in reality, it’s over 100 miles from the coast. I was beginning to

Our volunteer, my husband Mattheus, and I took the bikes down the coastline to see how much ground we could cover when we came across some good-sized brown bear tracks. Where else on earth can you watch a moose stroll on a sandy beach without any timber nearby, where do coyotes yips overlay wolf howls, and black and brown bears coexist with regularity? Not only that, but from Okalee Spit you could see the Steller Glacier, rising out of the ground and looming over the north end of the bay like an icy throne, pushing glacial silt and freshwater into the Pacific. And if that wasn’t enough, the highest coastal mountain range in the world forms the eastern backdrop to the bay. On clear days you could see Mount Saint Elias (the second tallest mountain in North America) rising 18,000 ft into the atmosphere in its snow laden glory. The Wrangel Mountain Range feels so close that you might be able to walk there in two days’ time but in reality, it’s over 100 miles from the coast. I was beginning to  understand what Steve meant when he said it’s “big country.” Everything felt large, ominous, and endless and yet so close to you at the same time.

understand what Steve meant when he said it’s “big country.” Everything felt large, ominous, and endless and yet so close to you at the same time.

For me the highlight of that short camping trip was when Mattheus and I ventured out and found a flock of 300 Red Knots. I knew this was a big flock. It didn’t matter that it was raining sideways and 40 mph gusts of wind were pelting our faces. I was glued to my spotting scope, watching their every move. I observed how they foraged, sticking the whole length of their bills deep  into the loose, wet sand and probing up and down a few jabs before finding whatever benthic organisms they were munching on. In a few instances, I could make out that they were eating small bivalves and they always seemed to stay near the water’s edge, never letting the water get too deep up their legs (they cannot swim even though their lives are tied almost exclusively to the ocean). After about an hour of this, Mattheus said, “Aren’t you cold? We’ve been out here sitting on the same flock of birds for a long time.” “Nope, this is what I came to do. I’m going to sit here until they leave,” I said. “This would be a great opportunity to do some fecal sampling and I don’t know if we will see another flock this large. But you can go make a fire if you want to.” My husband/volunteer was baffled. We had spent many days together out hunting, boating and camping and I generally always run cold, at least my hands always are, but he had never seen me as a biologist in action. “How long are

into the loose, wet sand and probing up and down a few jabs before finding whatever benthic organisms they were munching on. In a few instances, I could make out that they were eating small bivalves and they always seemed to stay near the water’s edge, never letting the water get too deep up their legs (they cannot swim even though their lives are tied almost exclusively to the ocean). After about an hour of this, Mattheus said, “Aren’t you cold? We’ve been out here sitting on the same flock of birds for a long time.” “Nope, this is what I came to do. I’m going to sit here until they leave,” I said. “This would be a great opportunity to do some fecal sampling and I don’t know if we will see another flock this large. But you can go make a fire if you want to.” My husband/volunteer was baffled. We had spent many days together out hunting, boating and camping and I generally always run cold, at least my hands always are, but he had never seen me as a biologist in action. “How long are  you going to be out here?” “Probably a few more hours.” He decided to go warm up by taking some laps on the bike and getting out of the wind up in the woods where we meet up a few hours and many poop samples later.

you going to be out here?” “Probably a few more hours.” He decided to go warm up by taking some laps on the bike and getting out of the wind up in the woods where we meet up a few hours and many poop samples later.

Big plans

I left Cordova in 2021 knowing that my aerial survey plans were trash, but it was possible to survey for Red Knots on foot (or in this case bike). Unfortunately, this was going to be a gargantuan task. Our budget had already been set and I couldn’t have known I need to survey 26 miles of coastline on foot when I wrote up my project proposal a year earlier. Erin was not deterred whatsoever. In fact, it made her all the more enthusiastic to pull together the people and resources needed to get the work done. We threw caution to the wind and dreamed big. Working with Steve to fly and land and fly and land in multiple spots, I selected four potential camping locations for crews in the bay. They needed to be close to a freshwater source, protected from the wind and any potential wave action, and most limiting, accessible by aircraft. Erin’s program had a Zodiac inflatable boat and all the necessary camping gear. It would be easy to convince her staff to go camping in the wet, wild and windy Controller Bay to survey for birds.

Next Month Part 2: Lessons learned pay off the following year, but not without storms, bears, and more bears.

All photos copyright ADF&G, by Jenell Larsen Tempel, Mattheus Tempel, Blake Richard, Evan Ward and Lyda Rees.

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) reviews programs and projects to ensure animal welfare. IACUC protocol numbers for work done for 2021: 0107-2021-34; for 2022: 0107-2022-25.

More on the Threatened, Endangered and Diversity Program at ADF&G

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.