Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2024

Capturing Sea Lions

Steller Sea Lion Research in Prince William Sound

The reversal drug worked quickly. The 700-pound Steller sea lion raised her head and looked around for her fellow sea lions. The rocky ledge jutting into the water of Prince William Sound was empty.

An hour earlier close to 50 Steller sea lions were crowded around her on the haulout, their bellowing roars carrying on the stiff October breeze. They were in the water just behind her now, but as she swung her head around all she could see was a group of sea lion researchers patiently watching to make sure she was okay. They spent the last hour equipping the darted and sedated sea lion with tracking devices and taking samples and measurements.

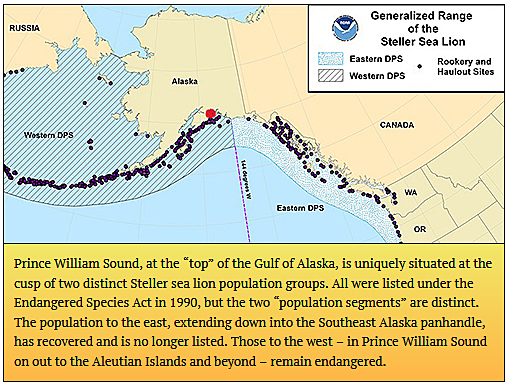

Because of widespread, unexplained population declines, Steller sea lions in Alaska are the focus of research. New technology is creating tremendous opportunities to capture these animals and learn far more than was possible even a decade ago. Recent events have not helped sea lions. The North Pacific Ocean marine heatwave of 2014 – 2016 was associated with an unexpected drop in adult female survival and pup productivity. Working with sea lions like this groggy female on Perry Island will provide valuable insights.

As her senses  sharpened she noticed her herd. She scooted to the edge of the outcrop and slipped into the cold water. She was likely unaware of the devices glued to her head and attached to her left flipper, which will provide a wealth of information for the next two years.

sharpened she noticed her herd. She scooted to the edge of the outcrop and slipped into the cold water. She was likely unaware of the devices glued to her head and attached to her left flipper, which will provide a wealth of information for the next two years.

Stalking sea lions

Two hours earlier a Naiad, a 15-foot rigid hull inflatable boat, approached an outcrop 400 yards away from the haulout – far enough that the sea lions were unconcerned. Boat officer Betsy Van Burgh nudged the Naiad against the rock, and as the swell lifted the bow, the two members of the darting party jumped ashore and slipped into the forest. They paused to shed their bright orange float coats, and wearing the forest-pattern camo favored by Southeast Alaska deer hunters, they readied their gear.

Their plan was familiar: climb the slope, circle over and drop down to a vantage point above the animals.  They’d target a female with a pup or yearling, ideally one they’d seen earlier from the Naiad, a marked animal with a known history. Wildlife veterinarian Annette Roug and biologist Justin Jenniges had light packs with drugs and darting gear, including the dart projector, which resembles an air rifle.

They’d target a female with a pup or yearling, ideally one they’d seen earlier from the Naiad, a marked animal with a known history. Wildlife veterinarian Annette Roug and biologist Justin Jenniges had light packs with drugs and darting gear, including the dart projector, which resembles an air rifle.

As they moved into position, the Naiad shuttled drone pilot Seth Bartusek to the drop-off spot.  By the time he was set up, Jenniges radioed that they were ready and described the position of the key animal. The Naiad and a 21-foot SAFEboat waited a few hundred yards offshore with the rest of the crew. Bartusek launched the drone and flew it over the haulout, hovering 150 yards above keeping watch over the featured sea lion.

By the time he was set up, Jenniges radioed that they were ready and described the position of the key animal. The Naiad and a 21-foot SAFEboat waited a few hundred yards offshore with the rest of the crew. Bartusek launched the drone and flew it over the haulout, hovering 150 yards above keeping watch over the featured sea lion.

When the dart hit, the sea lion flinched and looked around. Her big pup leaned over and smelled it. She moved a few feet, jostled her neighbors and the dart fell out. The pup lost interest. Sea lions bellowed back and forth and it was business as usual. But the next 15 minutes would be the tensest part of the operation.

This capture is possible only because of a new combination of drugs. In the past, drugs that would tranquilize a 700-pound sea lion could backfire. If she went into the water as it took effect, she could drown. The new drug combination is designed so if she goes into the water, she floats calmly and breathes. Biologists can motor up alongside her and bring her to shore for processing if conditions allow, or administer the reversal and set her free. That’s why the drone pilot keeps such a close eye on the darted animal. In a group of dozens of swimming sea lions milling about, the drone can help direct the crew to the right one.

This capture is possible only because of a new combination of drugs. In the past, drugs that would tranquilize a 700-pound sea lion could backfire. If she went into the water as it took effect, she could drown. The new drug combination is designed so if she goes into the water, she floats calmly and breathes. Biologists can motor up alongside her and bring her to shore for processing if conditions allow, or administer the reversal and set her free. That’s why the drone pilot keeps such a close eye on the darted animal. In a group of dozens of swimming sea lions milling about, the drone can help direct the crew to the right one.

Biologists need to plan for the worst. If the group spooked and flushed, she could get pushed into the water, and mixed in with the melee, drift off and be vulnerable to predation or a mishap. If nothing serious happened and they reversed her, it would still be a lost opportunity to tag and sample her.

After ten minutes, skipper Tom Gage eased the SAFEboat and crew of six toward the haulout.  Gage has worked in sea lion research for decades and carefully approached the best landing spot. Sea lions began slipping into the water, disgruntled by the intrusion but not in a stampede. The pup and a neighbor nudged the inert animal, when she did not respond they pushed her hard a few times before giving up and going in. As the haulout cleared, the crew jumped ashore and went to work. The Naiad fetched Bartusek and brought him over, and the two boats moved off to wait.

Gage has worked in sea lion research for decades and carefully approached the best landing spot. Sea lions began slipping into the water, disgruntled by the intrusion but not in a stampede. The pup and a neighbor nudged the inert animal, when she did not respond they pushed her hard a few times before giving up and going in. As the haulout cleared, the crew jumped ashore and went to work. The Naiad fetched Bartusek and brought him over, and the two boats moved off to wait.

Tagging

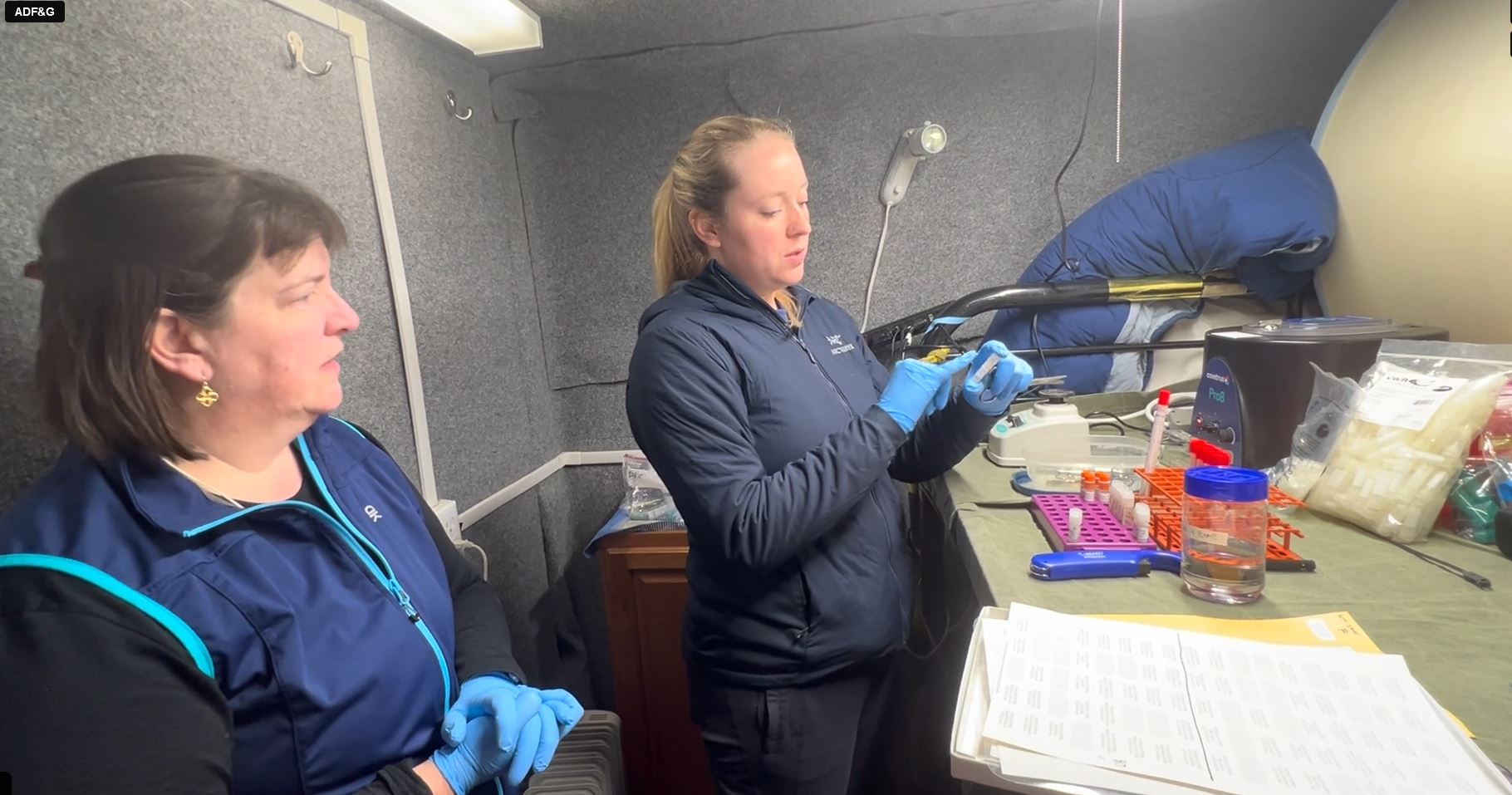

Veterinarian Emily Whitmer (a collaborator from The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, Cal.) joined Dr. Roug, and they intubated the sea lion and provided oxygen and anesthesia. They carefully monitored her vitals throughout the tagging.

Two satellite tracking devices are attached to the sea lion – a flipper tag and a head tag. The flipper tag (known as a SPOT tag) only sends locations. The more sophisticated head tag (a SPLASH tag) transmits her location (much more frequently and consistently), how deep she is diving, whether she is hauled out on land or is in the water, and the water temperature.

Jenniges used special pliers similar to a paper punch to remove a couple of pencil-eraser-size plugs of flipper gristle. This provides tissue samples for DNA and other analysis, and an attachment for the thumb-size transmitter. It only sends locations, but it lasts two years, sometimes longer.

Jenniges mixed epoxy to attach the head tag, a cell-phone size device with a short antenna. He brushed the top of her head with his fingers and plucked a few loose bits of fur, then cleaned and wiped it dry. Cracks and crevices in the rocks of the haulout were packed with brown sea lion hair and fur – the animals molt in late summer. That’s a big reason why this work is done in October – they’ve shed and it’s possible to epoxy the satellite transmitter to her head. It’ll come off in 10 months or so when she sheds again.

The tags show that some of those dives are remarkable. These researchers and their colleagues have tagged 25 sea lions in Prince William Sound and 18 in the Homer-Kodiak area in recent years. As generalist predators, individual animals develop foraging preferences – especially females, who have a pup to consider. Some dive shallow, some deep. Most forage close to the sea floor, no matter how deep the water. Some tagged at this very location might travel dozens of miles to a preferred feeding area and make shallow dives, others swim just a few miles but dive 400 meters, aiming for black cod and squid. The deepest dive was 600 meters, more than a third of a mile underwater, and lasted 10 minutes.

Jenniges smeared epoxy on the flat base of the transmitter, pressed it to her fur and carefully worked epoxy on the edges. He held it in place for 10 minutes as the epoxy set, surrounded by data-laden conversations. Many were single-syllable:

“Poking.”

“Punching.”

“DNA.”

Numbers were repeated back as they were recorded. Technician Greg Snedgen measured her length and girth, and pulled back her lips to measure her sharp canine teeth. The vets shared vitals – blood pressure, respiration rate, and conversed in low tones regarding her status.

Matt Piche, a biologist from Cordova with the Native Village of Eyak, took notes and filled data sheets. The tribe collaborates with state and federal biologists on sea lion research in the Sound. Since he lives in Prince William Sound, Piche capitalizes on weather windows to skiff out and check on animals when opportunities arise, do re-sights of tagged and marked animals at haulouts, and investigate possible mortalities.

At the back end of the animal, Lori Polasek, team leader and coordinator of the ADF&G Marine Mammal Program, smeared a dab of clear jelly on the sea lion’s hip and readied an ultrasound. The device and the procedure are the same as medical diagnostics, but this particular machine fits in a bright yellow waterproof Pelican case. Sarah Rauchenstein, a wildlife biologist focusing on animal welfare and vet-related work, passed the transducer probe to Polasek. She measured the thickness of the sea lion’s blubber through its fur and skin, narrating the procedure - she was also training Rauchenstein in ultrasonography.

They moved on to milking the sea lion. A sea lion’s nipples are nondescript, and they work exactly like they are supposed to. This female was barely lactating, as her pup was getting big. Jenniges and Polasek took turns kneading and palpating in typical milking fashion and coaxed a few ounces of creamy thick milk, brilliant white against her dark fur, and collected it.

As biologists completed their tasks, they packed up instruments and carried the gear to the water’s edge. The tide was falling so it was safe to stage for the pick-up. Polasek fetched a five gallon bucket with a tight-fitting lid and unloaded white plastic spoons and Ziplock bags; it was time to collect fecal samples, a process that is worse than it sounds but a good way to analyze what sea lions eat.

As biologists completed their tasks, they packed up instruments and carried the gear to the water’s edge. The tide was falling so it was safe to stage for the pick-up. Polasek fetched a five gallon bucket with a tight-fitting lid and unloaded white plastic spoons and Ziplock bags; it was time to collect fecal samples, a process that is worse than it sounds but a good way to analyze what sea lions eat.

The crew surveyed the area for dead sea lions (for possible sampling and necropsy) and none were found. Jenniges had already retrieved the dart. Everything was ready and Dr.  Roug administered the reversal drug and Dr. Whitmer prepared to remove the intubation – she attached a cord to the endotracheal tube so it could be pulled from the animal’s mouth from a safe distance. The sea lion was still getting oxygen, and as she began stirring Whitmer tugged the cord and gathered up the final piece of gear.

Roug administered the reversal drug and Dr. Whitmer prepared to remove the intubation – she attached a cord to the endotracheal tube so it could be pulled from the animal’s mouth from a safe distance. The sea lion was still getting oxygen, and as she began stirring Whitmer tugged the cord and gathered up the final piece of gear.

As the boats pulled away from the rocks the sea lions returned to the haulout. The tagged sea lion swam by underwater, the tag clearly visible on her head.

Back at the Dream Catcher

The support vessel Dream Catcher was anchored in a quiet cove on the other side of the island, a bouncy 15-minute ride from the haulout. Unloading was methodical – all the gear was staged on the swim step and sprayed down with a bleach solution, then hosed off. Same for the researchers. Float coats and bibs were hung in a walk-in gear locker, boot dryers were available but not required on this day.

The final step was a visit to a cryogenic tank, a container similar to a pony keg, with liquid nitrogen at 320 degrees below zero Fahrenheit. A frosty cloud wafted out as Rauchenstein unfastened the lid and she stashed the appropriate samples inside.

Debriefing

The warm dining room/galley was the evening workroom, as is the case in most field camps. Bartusek reviewed drone footage with Piche, and I asked Jenniges about stalking sea lions. He said they have a surprisingly acute sense of smell and good hearing.

“They key in on what doesn’t smell like a sea lion,” he said. “You can sneak up on a Steller sea lion with no cover if they can’t smell you. If you have the wind in your face and take your time. If the wind shifts (and they catch your scent) they look around.”

He said the ones highest up on the haulout, closest to the woods, react the strongest. He said that morning several had been spooked when a flock of crows flew nearby.

“They get spooked by ravens, the sound of rocks clattering, and they flush and go for safety, they go in the water. And the others will follow. So, you try to find someone in the middle. One with fifty other sea lions around them. When you dart them, they think someone bit them. They look over, “Why did you bite me?”

After the dart hits, it takes three seconds to deliver the full dose. The dart projector is CO2 powered and the pressure is adjustable, and Jenniges dials it in appropriately. A high setting will send the dart flying hard and fast, but that’s not what he needs.

“You try and lob it and get less impact,” he said. “They’re less likely to startle and go in the water. You don’t want to aim too high and hit someone else that’s behind her. Since I’m always aiming downhill, I aim lower.”

“I aim for the shoulder or the back. It’s best if they can’t see it. If they see it they keep looking back at it, they see it moving and flexing, they smell it and react. When it falls out they don’t care anymore. They calm down. If it falls next to them, they sniff it and just move away.”

Jenniges has been doing this work for 20 years, and some of his colleagues have been researching Steller sea lions for close to three decades. They remember when having scuba divers lasso juveniles was the best way to capture sea lions. When biologists picked bones out of scat to identify prey, rather than analyzing the DNA. Before a sea lion’s whisker could be tested for mercury, heavy metals and toxins.

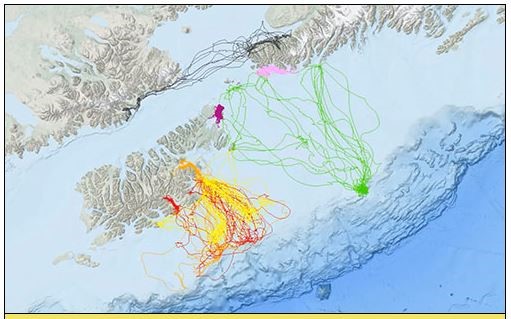

The tracking devices will help with disease tracking and help identify sea lions’ critical habitat and areas important to the animals’ survival – places they may or may not visit at the same time year after year. They’ll help explain why an animal might swim from Kodiak Island to Prince William Sound, or down into Southeast Alaska’s Inside Passage, and then return. The image above of Kodiak island is a good example: the map shows the movements and tracks of the seven sea lions, represented by different colors, in the Gulf of Alaska south of Kodiak Island in the fall and winter following tagging there in 2020 by this same project. The ocean floor off the continental shelf is in the lower right corner. A video of the movements over time can be viewed via a link at the end of the article.

By the end of the trip researchers tagged nine more sea lions, including one that had been captured 19 years ago as a pup. She provided biological samples and movement data as a pup in 2005. Resights over the years documented her continued survival and reproductive status. Now she is providing insights as a 19-year-old mother.

By the end of the trip researchers tagged nine more sea lions, including one that had been captured 19 years ago as a pup. She provided biological samples and movement data as a pup in 2005. Resights over the years documented her continued survival and reproductive status. Now she is providing insights as a 19-year-old mother.

Riley Woodford is the editor of Alaska Fish and Wildlife News and produces the Sounds Wild! radio program. He has been writing about Steller sea lion research since 2003.

All research and capture work is done under NMFS MMPA/ESA Permit No. 27503.

More on Steller sea lions

Steller sea lion movements in the Gulf of Alaska – animated video. Satellite-tracked movements of 7 adult female Steller sea lions captured in the central Gulf of Alaska, October 2019 - June 2020 by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Each color is a different sea lion. Video speed is one day per second, and the track-lines update twice per day.

Video and good audio of Noisy sea lions in the water off Perry Island

Video and audio of sea lions at a Perry Island haulout

Steller Sea Lions species profile

Sea lion moms foraging in winter (An article on this project with more information on movements and diving, from 2020)

Traditional Uses of Steller Sea Lions

Documenting Steller Sea Lions Using Time-Lapse Cameras

Helping sea lions “loose the loop”

Reducing Steller Sea Lion Entanglement in Marine Debris

Steller sea lion research overview ADF&G

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.