Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2024

Killed by a Quill

The story of a ragged old wolf and the importance of necropsies in wildlife mortality investigations

Many aspects of life are relative. Sometimes a comparison of situations is helpful to put things into perspective. For example, I was feeling my own aches and pains as I recovered from a series of orthopedic surgeries this summer. Then, a friend of mine called to talk about a wolf he had just live-captured as part of a research project in Southeast Alaska. The story was amazing and became more so as we investigated and learned more.

Neil Barten, a retired Fish and Game biologist was live-trapping wolves in Southeast Alaska recently as a part of an ongoing wolf research project. It’s tough trapping in the area he was working. There aren’t many wolves, and they are very wary of people and trap sets. So, he was happy when he checked his traps one morning and had captured a wolf to place a GPS collar on.

This wolf, however, was not what he was hoping to find. It was an old-looking, emaciated animal that had a lot of porcupine quills in its mouth. Wolves don’t normally prey on porcupines because of the potential consequences that quills provide. A mouthful of quills can range from a painful inconvenience to a deadly affair.

Barten sedated this wolf, put a radio collar on the animal and even removed a lot of the quills from its muzzle. He then let the animal go, all the while concerned about its physical condition.

Iridium GPS collars transmit locations by satellite, allowing researchers to watch the whereabouts of collared wolves. Four days later, and a couple miles distant, the GPS collar sent a mortality alert and location by email. This signal coming from the collar indicates that the animal has not moved in a certain period (six hours, in this case), meaning that it is likely dead. So, Barten went to investigate the mortality signal as soon as possible. It is always best to get to a mortality site as soon as possible to observe fresh signs and other evidence before scavengers and weather have a chance to affect the scene.

This old wolf was indeed dead when Barten got back to it. The story he witnessed from observing the tracks and the vegetation showed an ugly altercation.

“I witnessed lots of fur clumps and broken vegetation along what appeared to be the route of a running fight, with two main battle areas.”

It appeared that our old, emaciated wolf had been attacked by other wolves. Likely a territorial attack or a dominance/challenge attack. In any case, the collared wolf was no longer alive.

What can we conclude from the evidence so far? Was the old wolf emaciated because it attacked a porcupine and ended up with a mouthful of quills? Did he attack the porcupine because he was already weakened and could no longer take other prey? Did the other wolves attack him because he was weakened or because he was in the wrong place? One thing that the scene strongly alluded to is that he was killed by other wolves — the most common cause of death among wolves — intraspecific competition. As Barten points out, “In many cases, this would have been the end of the story, i.e. an emaciated wolf gets attacked and killed by other wolves…however, thanks to an inquisitive veterinary staff, we were able to pinpoint the ultimate demise of this wolf.”

Neil shipped the dead wolf to ADF&G’s office in Fairbanks so that wildlife veterinarian, Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen, could perform a necropsy. A necropsy is basically an animal autopsy. A detailed dissection and investigation of the animal to find a cause of death.

Dr. Beckmen has done thousands of necropsies on all types of wildlife- from polar bears to songbirds. She has done over 300 on wolves, alone. During a necropsy there is sometimes obvious, gross damage visible and other times there is not.

Tissue samples and swabs are usually taken from various regions of the body and sent to labs for testing to detect anything from viruses to heavy metals. Often there are underlying causes to an animal’s death that are not visible. Some animals have diseases, some are poisoned, etc. An underlying cause may have put an animal at risk for the primary (more visible) cause of death. It is important to investigate and not to assume.

A few years ago, I observed a wolf necropsy with Dr. Beckmen that was quite a surprise. A dead wolf was found on a snowmachine trail. Apparently with no gross, obvious wounds other than some caused by scavengers and one hole in the ribs that some assumed was from a bullet. There were a lot of assumptions and speculations about the animal’s death. It wasn’t until the necropsy was underway and the animal skinned that evidence was revealed. Although there was no obvious broken skin or tears to the hide, when the skin was peeled back, the neck meat showed deep lacerations and punctures. The neck muscles were basically torn apart and ultimately a fatal puncture to the thoracic cavity, through the ribs, was identified.

The wolf had been attacked and killed by other wolves. Although the hide was not penetrated, the damage from the teeth had done their job. A lesson learned. Wolves have very tough skin, and you can’t judge a carcass by its cover.

Studying predation patterns of wolves in Southeast Alaska

The old wolf that Neil Barten had captured, wolf number 202401, was one of 23 wolves captured in Southeast Alaska and equipped with GPS collars to study predation patterns. This project was initiated in the spring of 2018 by Gretchen Roffler, the predator-prey research biologist in Southeast Alaska (Region I) to learn about seasonal differences in prey selection, how habitat and environmental conditions may make prey more vulnerable to wolf predation, and characteristics of the prey (age, sex, and body condition). The predation research team includes Wildlife Biologist Alex Lewis and is assisted by many Region I management biologists and seasonal research staff members. They receive the wolf GPS locations daily by email. These locations are filtered through an algorithm to create clusters – places the wolves have spent enough time to warrant investigation. The team then hits the ground to search each site for evidence of a wolf kill.

Over the course of 12, month-long field seasons, the predation research team has investigated 1,248 wolf GPS clusters and collected information about prey at 368 sites. These sites are in six study areas that span the diverse Southeast Alaska environment including the rugged mainland where moose and mountain goats dominate wolf diets, and forested islands where Sitka black-tailed deer are the most common prey.

Wolf 202401 was captured in the Gustavus forelands, a low elevation coastal environment where wolves specialize on moose, but also prey seasonally on marine mammals and salmon. Researchers can also determine cause of death of these collared wolves if investigated promptly. Although most are killed legally by trappers, 38% of the wolves in this study have died by “natural” causes – a category that includes starvation, disease, trampling by moose, and death from wolves in another pack (also called “intraspecific strife”) – all of which have occurred to the wolves in this study as revealed by mortality investigations and timely necropsies.

Old wolf 202401

With our current wolf, the necropsy began. Tooth wear provided an age estimate of about 9-10 years. Getting up there in age for a wolf in the wild as the rest of the investigation would reveal.

The rear of the mouth of the animal was full of quills and some of them had migrated deep into the masseter (cheek) muscles causing necrosis. It was an awful sight, and I could imagine that this wolf could no longer eat.

Continuing throughout the process, there were multiple fresh lacerations in different areas on the animal caused by the recent wolves attacking it, but nothing fatal.

The 5th and 10th rib on the left side had old breaks that had healed over. It is not uncommon for wolves to have healed broken bones considering their propensity to take down large ungulates.

In addition, the necropsy findings also included: missing and broken teeth, severe dehydration, muscle necrosis, hemorrhages in the lumbar muscles, contusions on the lungs, and hard swelling and restricted flexion of the right wrist from a break or dislocation.

But where was the smoking gun? So far none of these injuries proved to be the death knell. What had finally killed this emaciated, beat-up old dog?

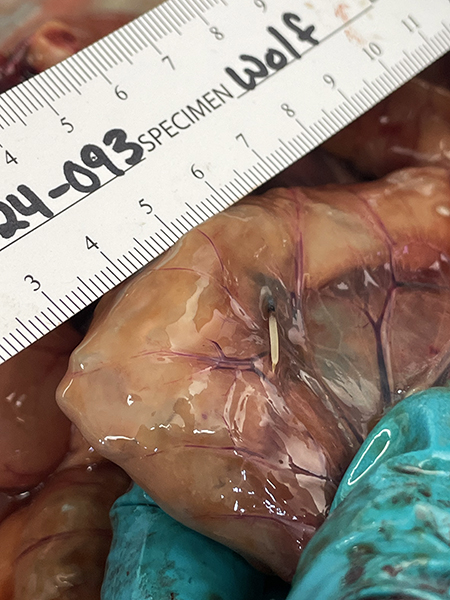

Dr. Beckmen continued to systematically inspect the organs and take samples. Then, when she cut into the abdominal cavity there was some brown fluid present. Not a good sign. This indicates fluid leaking from the intestines. She cut down the intestines searching for a perforation. Then, when she got to the jejunum (the middle part of the small intestine) there was a single porcupine quill sticking through it, penetrating the intestine and leaking fluid into the cavity. This fluid leak caused sepsis which severely sickened the animal (which would have been fatal in a short time).

The conclusion from the necropsy report:

This wolf was likely already suffering from difficulty in predating due to lameness from a right front leg injury (broken or dislocated wrist). It probably preyed on a porcupine in desperation. The quills in the jaw muscle further made eating difficult. Over time it was pawing and swallowing quills. One penetrated the intestinal wall from inside to outside causing digesta to leak into the abdomen causing peritonitis. Other wolves attacked it while it was down but none of those wounds were fatal.

So, first there was a fractured/dislocated carpus. The wolf couldn't hunt efficiently. It attacked a porcupine, got an infected masseter muscle, couldn’t eat/drink, a quill caused peritonitis, the severely weakened animal suffered conspecific attacks, then dies.

What a way to go. When you are old and broken and beaten down and dying from sepsis, to have other wolves come tear you up. Wow. Such is their life out there in the wild.

My own suffering began to pale as I contemplated the final days of this old wolf’s existence. People tend to judge wildlife with a fair bit of anthropomorphism, applying attributes that don’t really exist in nature. The reality can be quite shocking to our emotions when we witness it, yet these situations play out every day, everywhere, to all wild animals. Fortunately for us, or maybe unfortunately, we are usually shielded from witnessing them.

More

A selection of publications of Roffler's wolf research

Wolf research on Prince of Wales - Inside the wolf den

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.