Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

June 2005

Gustavus Moose on the Move

Biologists Track Seasonal Movements

Every winter moose invade Gustavus, and every spring they virtually disappear.

Residents of Gustavus, a small southeast Alaska town located just outside Glacier Bay National Park, remember the first time a moose was seen in the area, around 1966. The moose population has boomed since those first moose colonists arrived, and in recent winters, seeing moose in and around town is a daily experience for Gustavus locals. Between April and September, however, moose sightings become much less common, raising the question, “Where do all the moose go during the summer?”

Biologists are well acquainted with the migration in wildlife populations. Nevertheless, not all populations migrate, and those that do migrate don’t always exhibit similar patterns. Take, for example, the champion Alaskan migratory species, the barren-ground caribou. Some Arctic-dwelling herds of this amazing species travel as many as 400 miles between their summer calving grounds on the Arctic coastal plain and their over-winter habitats near the Bering Sea. On the other hand, coastal mountain goats might migrate just a few miles between their low-elevation winter habitats and their summer ranges on alpine ridges - and some individuals might not migrate at all. For biologists, the chance to learn about migratory patterns of an unstudied population promises to be an exciting endeavor. This is where Gustavus moose come into the picture.

In December of 2003, researchers from the Alaska Department of Fish and Game began a study of moose ecology on the Gustavus forelands. To better understand the seasonal movement patterns of these animals, eight GPS-linked radio-collars were attached to cow moose. GPS (global positioning system) technology has long been used by the military but has only been available for use by everyday citizens since 1993. GPS technology relies on 24 satellites that orbit the globe. Communication with earthbound receivers, such as those attached to moose collars, allow biologists to pinpoint the locations of those moose to within 3 to 20 meters. This has enabled biologists to learn about how moose use their environment like never before. For example, researchers now know where particular Gustavus moose were every three hours over the last year.

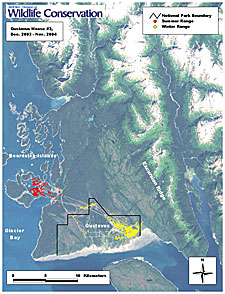

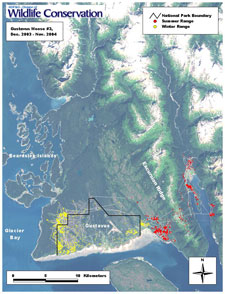

Before the study began, biologists had only a vague notion where the 450-plus moose that spent their winters on the Gustavus forelands went during the summer months to have their calves. Now, thanks to GPS technology, it is firmly established that the Gustavus moose population is largely migratory with some animals traveling up to 30 kilometers between distinct winter and summer ranges. Not only do moose travel significant distances, but they travel to unusual places as well. About 25 percent of Gustavus moose spend their summers in the Beardslee Islands in Glacier Bay and, in some cases, swim between islands on a regular basis. Other moose, adopting a strategy more akin to mountain goats, spend their summers high up in the rugged alpine terrain of Excursion Ridge east of Gustavus. And some moose are “homebodies,” who spend their summer season in nearly the same place they spent the previous winter.

While understanding the variation in migration patterns of Gustavus moose has provided biologists with key information for conservation and management of this population, it is also in many ways a classic case study of wildlife research in action; biologists now have more questions than answers. Why do moose swim out to the islands, or climb to the alpine, to have their calves? Are there fewer predators, or are food resources more abundant in such locations? Are moose that migrate to the islands more closely related to each other than to those that migrate elsewhere? Do moose always migrate to the same place every summer? These questions and many others beg to be answered. As research continues, biologists look forward to meeting the challenge of answering these questions…and, of course, posing new ones.

Moose researcher Kevin White is a wildlife biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.