Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

February 2024

Prince William Sound Black Bears

Potential Changes for 2024

Prince William Sound is prime black bear habitat. Ringed by the rugged Chugach Mountains, the sound is a network of forested islands and convoluted fjords, sitting at the “top” of the Gulf of Alaska. The area is popular with bear hunters and the number of black bears harvested in the sound has doubled in recent years. The growing harvest is noteworthy for wildlife managers, who work to balance hunting opportunity with a healthy and sustainable bear population.

The area is very productive for bears, until a year comes along that isn’t. Weather affects bear productivity and cub survival, and also affects hunter access and success – influencing where hunters can go and where bears will be. Most hunters use boats to reach shorelines and islands in Prince William Sound. Although some bear hunting occurs in the fall, about 80 percent of the harvest is in the spring. Most participants come from Anchorage and the Mat-Su area, driving down through Whittier. Historically, the bulk of harvest is Memorial Day weekend – it’s a long weekend and it’s consistently busy with both hunting and fishing opportunities.

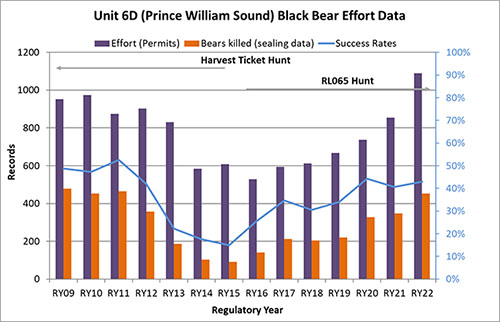

Wildlife Biologist Charlotte Westing will be watching the spring hunt closely this year. Harvest has varied from more than 500 black bears some years to fewer than 100 in others. Take has been steadily rising since 2015, and effort is high. More than a thousand hunters took 467 black bears in Prince William Sound in the last regulatory year (2022 which extends into calendar year 2023).

Westing is the area biologist, based in Cordova. She’s done years of research on the Prince William Sound black bears, collaborating with now retired Forest Service biologist Milo Burcham (most of the land surrounding the sound is part of the Chugach National Forest). Looking at past patterns and what they’ve learned from captured and GPS-collared black bears she’s urging hunters not to shoot female bears. Overall harvest will be capped in the 400 to 450 range.

Westing wants hunters to know the registration hunt can close fast by emergency order – and hunters might consider hunting earlier in May and not focus on the Memorial Day weekend – it could be closed by then. Hunters have three days to report their harvest. Although the season can potentially run until June 10, the season may close early if the take of females is too high, and if the overall take is getting too high. If the season closes early, it could potentially shut down before Memorial Day weekend.

“If hunters harvest mature males, that’ll keep the season open longer for everyone,” Westing said.

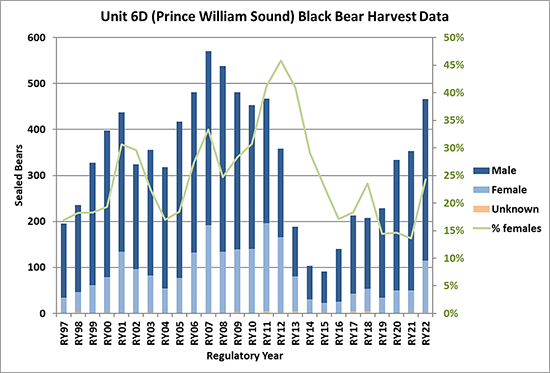

Why limit the harvest – and focus on male bears?

The annual black bear harvest in Prince William Sound has increased dramatically in recent decades. In the 1990s, the annual harvest was less than 200. It more than tripled between 2000 and 2006 – the bear harvest graph below shows the harvest numbers. In 2008 and ’09 it was well over 500. Most of Southeast Alaska is prime bear habitat with fairly low hunting pressure, and if 25 percent of the harvest is female bears, the population is sustainable. In the late 1990s, the harvest of female bears was below 20 percent. For most of the first decade that hunters were hitting the sound hard, the harvest of female bears was above 25 percent. In 2011 and ’12, high hunter effort, high female harvest, high harvest overall, and potentially poor cub survival converged. In the years that followed, hunter success plummeted.

It’s illegal to harvest a female bear with cubs. Bear hunters in the field, spotting a potential animal, need to watch it closely, think about the gender and look for cubs. Since most hunters want a big bear with a really nice coat, they tend to look them over carefully, passing on bears with rubbed fur, bald patches, small bears and of course, mother bears with cubs. But while a female bear without cubs is legal, they are also critical to building the population. With a little bear-watching practice, a good hunter can differentiate between male and female bears, and pass on the potential mother bears.

Cubs are born in the den in mid-winter, and a sow typically gives birth every other year to between one and four cubs. Black bears tend to keep their cubs with them for a year-and-a-half, teaching them life skills their first year, hibernating with them that winter, accompanying them early the subsequent spring and then in late spring mating and “emancipating” the yearling cubs. Westing noted the implications of that.

“Every other year of a female’s life, the presence of cubs means she’s off limits to hunters. If you have a big year when cubs don’t survive or aren’t produced, you may have up to twice as many female bears on the landscape available to harvest. It could be a double whammy for your population, you are killing your breeding females and you’re not gaining cubs.”

Biologists believe that may have happened in Prince William Sound. The sound was buried in snow in the winter of 2011 - a three-week storm in January dumped 18 feet of snow on Cordova. The “snowpocalypse” of 2011 was followed by two more winters with heavy snowfall and late springs. We think cub survival was poor those years, Westing said. The adults can weather a tough spring, but the cubs don’t make it.

“In 2011, the first big snow year, bears came out of the dens and it was well into June before food was available,” she said. “They lost a month of the growing season, and the next year, and the next.”

To make matters worse, those unproductive years followed a decade of phenomenal bear hunting in the sound, and hunter effort was at an all-time high. Here’s why:

Before June 2000, the Portage Glacier Highway dead-ended at a railroad tunnel about a 45-minute drive from Anchorage. Access to Whittier, in Prince William Sound, was by railroad. The train could accommodate passengers and about 20 vehicles on a flatbed railroad car. About 20,000 people traveled this way each year. That changed in 2000 when work was completed, modifying the tunnel to accommodate traffic. Overnight, Whittier became an hour-drive for half the population in Alaska. Whittier saw 120,000 visitors that first year, and annual numbers settled at about 100,000 visitors. Many people trailer boats or keep boats in Prince William Sound. Over the next decade, black bear harvest tripled.

As the bear harvest graph above shows, after the high harvest between 2000 and 2010, effort remained high even as the number of bears harvested plummeted. Wildlife watchers, charter operators, commercial fishermen and others reported they were seeing fewer bears. A lot fewer bears.

“We want a quality experience for all kinds of users - transporters, guides, wildlife viewers, and hunters,” she said. “After 2013, no one was happy.”

The harvest ticket-managed hunt became a registration hunt in the fall of 2015 to allow closer monitoring. That spring, Westing also closed the season early for the first time. A maximum allowable harvest for black bears was set at 200. Over subsequent years as bear numbers increased, that was bumped up to 300, then higher. In the late twenty-teens the harvest of females fell below 25 percent, a good thing, and even dipped close to 15 percent.

Other factors come into play in bears’ favor, such as a year with good berry production with plentiful blueberries and salmonberries. A good salmon return – and there have been some good years for pink salmon. A year with less snow and an early spring. Early green up has several benefits – bears come out earlier and begin feeding, and can also move up to higher elevations where they are less accessible to hunters in May.

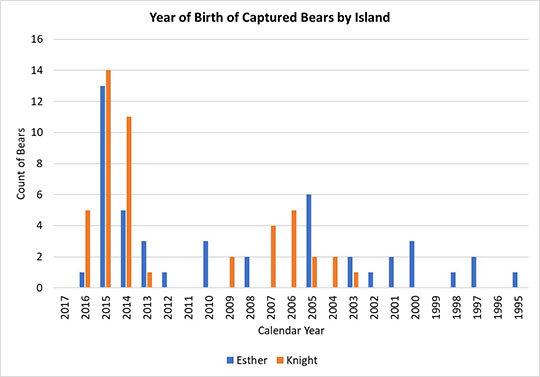

Westing has been learning a lot about the Prince William Sound black bears. She and Burcham captured and examined 96 black bears in the summers of 2016-2018 and equipped over 50 with GPS tracking collars to study their movements and habitat use. One thing jumped out when they looked at the age of the bears.

“When we captured bears, almost 100, we had old bears and young bears, but we had missing years,” she said. “We did not capture any bears that were born in 2011. It suggests, if you were a cub that year, you might not have made it.”

As the birth year graph shows, of those 96 bears, only one was born in 2012, and only four in 2013. In 2015, that jumped to 27. Cub survival and recruitment increased after those tough years, but hunter effort and harvest has also increased.

“Looking at the harvest records, a lot of the recent harvest is young animals,” Westing said. “This could be a reflection of the success of those recent age classes – but it could also be hampering recruitment and impacting growth of the population.”

Westing would like to see female harvest stay below 25 percent. More females means more cubs. Even older female bears can produce cubs.

“In the course of the study, we handled a 25-year-old female who had a cub,” she said. “It’s pretty remarkable.”

Westing and Burcham are working on several papers based on their recent research. One will look at bear distribution in the spring and the factors that may influence distribution since that could impact how accessible bears are to hunters.

She wants hunters to be able to determine the sex of bears, and to target males. An educational guide, Hunting Black Bears in Coastal Alaska, Units 1-6, is recommended, and is available online or in area offices.

“I’d like to build on what we’re learning and soften these wild oscillations,” she said. “Populations can oscillate, but we like stability, consistent opportunity and predictable resources.”

More resources

2016 AFWN article about this project Collared Bears Provide Insights

2019 AFWN article: Black bear research in Prince William Sound

Black Bear Species Profile

Hunting Black Bears in Southeast Alaska, Units 1-6 (PDF 2,038 kB) If you want a copy mailed to you, email riley.woodford@alaska.gov

Black Bear hunting in Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound wildlife viewing

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.