Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

December 2023

Studying Ringed Seals in Winter

with the Help of Detection Dogs

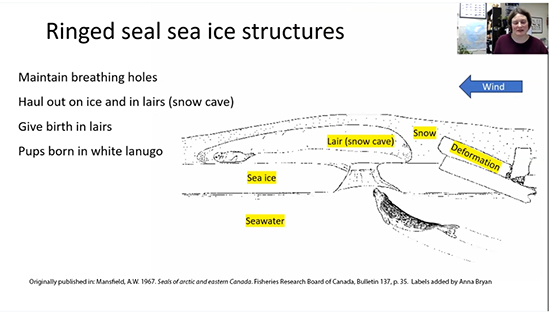

Ringed seals live a secretive life beneath the snow-covered landscape of Prudhoe Bay in winter. They catch fish and invertebrate prey in frigid Arctic Ocean waters and haul out to rest in icy lairs hidden beneath snow drifts. They create and maintain breathing holes and access holes – vertical watery tunnels through the sea ice as much as two meters thick – allowing them to use habitat both on and under sea ice during the winter.

Wildlife researchers are documenting how these ice-adapted seals use Prudhoe Bay, a nearshore oil and gas production area. Seals live, pup, and forage near seismic and drilling operations, and in areas where ice roads and gravel islands are built. They spend most of their time underwater and hidden in their lairs, so determining how many seals may be affected by oil and gas activities is difficult, but necessary, for attaining permits to conduct these activities. Finding those lairs and breathing holes is important, and trained wildlife detection dogs are valuable team members in this work.

In early November, 2023, Fish and Game marine mammal biologist Anna Bryan delivered a 30-minute presentation with video and pictures, detailing how wildlife detection dogs help researchers find ringed seal “structures” like breathing holes and lairs on the landfast sea ice. Using wildlife detection dogs to help determine ringed seal density

Researchers worked with the dogs to survey an area in Prudhoe Bay near Northstar Island that was previously studied in 1983. The roughly rectangular study area was about 8 miles by 4.5 miles (13 x 7 km and 88.2km2), and lays between Prudhoe Bay and Reindeer Island, one of the barrier islands just offshore. Water beneath the ice is shallow, typically between 2 and 15 meters deep.

The dogs, Stout and Indigo, are a brother-sister team of black Labradors now five-and-a-half years old. They were trained to find seal scent using flippers from subsistence-harvested seals. They started at a young age learning basic commands, then whistle commands and hand signals, then advanced to more complex situations like working with snow machines.

“We really need the dogs to run in front of the snow machine,” Bryan said. “Training the dogs to run in front and have the confidence to be in front of us rather than behind is really important. We also need the dogs to be comfortable riding inside of a kennel on a sled behind a snow machine - this can be kind of challenging and not all dogs like it. Sometimes we run both dogs together, sometimes we only run one dog. When we’re running like this, we tend to run about 11 miles per day.”

The Inupiat word for ringed seal, “Natchiq,” is used to initiate a search. The dogs search quartering into the wind, running at 8 to 15 mph. They “alert” when they catch the scent and then quickly change course, heading to the source. The scientists follow close behind on snow machines.

“This is an airborne scent, so the dogs smell it up in the air and not on the ground,” Bryan said. “These dogs run faster after they catch a scent, they’ll run up to 25 miles an hour as they are going in toward the scent if the wind is steady. Once they reach the structure they stop, and we get off and inspect the structure.”

Sometimes a breathing hole is right in the open, and not associated with a lair. Other times they are under the snow, and the dog begins digging. The scent may emanate from multiple places, so the researcher uses a snow probe to feel the icy ceiling of the lair, or punch through to the breathing hole and into the water.

Ringed seals are an important subsistence resource to coastal Alaska Natives, and important prey for polar bears. Ringed seals were listed as threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2012 because predicted declines in sea ice and snow accumulation over the next century were expected to greatly reduce their numbers.

There are four species of ice seals in Alaska, ringed, bearded, ribbon and spotted. Ringed are the smallest, the most ice adapted, and an important subsistence resource for Alaskans. They have a circumpolar distribution, and more than 470,000 are estimated in Alaska waters.

The dogs and researchers found more than 130 seal structures in Prudhoe Bay in two seasons. Bryan said Prudhoe Bay is not a high-density area for ringed seals, and researchers would expect to find more seal structures in high density seal areas.

“These are different structures each year,” Bryan said. “They all disappear when the sea ice melts out and they make them again in the next season.”

In 2022, researchers and dogs found 61 seal structures (47 breathing holes, 13 haul-out lairs, and one pupping lair) at a density of .69/km2. In 2023, they found 73 seal structures (60 breathing holes, nine haul-out lairs, one pupping lair, and three unknown structures) at a density of .83/km2.

Motion-triggered trail cameras were deployed at nine breathing holes in 2023. Temperature probes were also deployed at the seal lairs, and temperatures could be detected and compared inside and outside the lair. The seals’ body temperature warms the lair, documenting time of day and length of haul-out bouts.

The cameras also offered additional and unexpected behavior. The researchers were surprised to learn how often seals come up to rest and sleep in the access hole with their nose poking out of the frigid water but without hauling out in the lair. The time spent in lair access holes did not register on the temperature probe. They documented 78 such bouts longer than 30 minutes, averaging about an hour and 45 minutes and lasting as long as 10 hours.

The two years of field work were funded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Researchers will now write up their findings and compare what they’ve learned to previous information.

For more information

Presentation with video of dogs searching and finding seal structures, underwater footage below lairs, and footage inside lairs: Using wildlife detection dogs to help determine ringed seal density

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.