Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

October 2022

How to Become a Bird Nerd

Beginners Guide to Birding in Alaska

When I was growing up in rural Alaska, an unusual bird landed in a stand of dried pushky (cow parsnip) outside our window one day. It was larger than the typical Golden-crowned Sparrows and dusty colored with a black mask and orange blush.

My family had a 20-year-old book of Alaska birds and the bird seemed to match the grainy photo of a Northern Wheatear. It was with some veneration that my mother read from the book that the little bird had most likely flown here from Africa.

To my young mind, that was almost incomprehensible. That little gray bird had flown from the other side of the planet, crossed Asia and the Bering Sea to join the seagulls and warblers that I watched from the porch? Several months beforehand, that bird had been in Africa, and now I could hear it singing in Southcentral Alaska. Who else was around our small cabin? I knew the Bald Eagles and Ptarmigan in the surrounding tundra, but what of the penguin-looking seabirds? The bright yellow warblers, and the delicate nests of baby birds hiding in the salmonberry bushes?

What is Birdwatching?

Birdwatching, or birding, is a form of wildlife viewing. Birders seek out and identify bird species in their natural habitat. It is an incredibly accessible form of nature observation, as birds are ubiquitous across all continents, across the land and ocean, and found from pole to pole. In Alaska you will see birds on your front porch, in dense urban areas, in the open Bering Strait, and on the vast barren tundra. You’ll see birds that spend most of their lives on the water, that can tunnel into the earth, birds that fly double the length of the planet in one year, and birds that nest in the open on stony mountain ridges and in delicate moss caves in the wetlands.

It is no wonder then that so many Alaskans have taken to birding and embarked on life-long scavenger hunts that can encompass either their own community or the entire world. There are some 500 species of birds found in Alaska; many are migratory species and “only” a few hundred occur year-round in the state. Alaska is in fact a unique hotspot for birdwatching because of our incredible size and diversity of bird habitat, and our proximity to Eurasia, the Arctic Circle, and the biggest ocean in the world. Birds that summer in Alaska have been found wintering in every other continent on Earth. Habitats in Alaska host nearly 100 million seabirds each year, as well as 12 million shorebirds – the world’s largest concentrations, and 20 percent of the country’s breeding population of waterfowl species. For many of these species, the entire continental breeding populations are found in Alaska each summer and can be seen nowhere else.

Alaska is a global destination for birders. The unmatched viewing opportunities and the incredible biomass of Alaska bird species brings economic opportunity to our state. Birdwatching is a fast growing brand of nature-based tourism that brings hundreds of thousands of eco-tourists to Alaska each year, yielding millions of dollars and supporting thousands of jobs.

Becoming a Birder

Birders by and large keep a list of birds they see, and birding in Alaska involves seeking out our native bird species and noting when you see a bird in the wild (or at your feeder) for the first time. This is called a life list, and identifying a wild bird by sight or sound for the first time is known as getting a “lifer.” Learn to identify the common birds in your area. Can you find all the bird species in your community? In the state? Who’s the little songbird you see coming to your birdfeeder every day? The slender-necked water bird with bright red eyes in your local lake? The small penguin-looking bird bobbing near your shrimp pots?

How many species can you identify? How many can you see or hear in a lifetime?

Look at the habitat you are in and the time of year. Are you in the mountains? The wetlands? The coast? Different birds live in different habitats, and what your local area offers will affect the species that you will be able to see. In the fall, many bird species migrate away, and the number of options will be smaller, which can also make identification easier. However, many seaducks and marine birds migrate to coastal and Southeast Alaska for the winter, providing great new birding opportunities. And spring and fall offer chances to see migrating birds on the move. See who is in your area by doing a bit of research. Audubon Alaska is a great resource to start, offering species checklists based on region and time of year.

Pick a place to search for birds. This can be sitting on your porch, walking your favorite hiking trail, or looking for local hotspots where many different species have been seen. Alaska eBird offers maps showing birding hotspots where other birders frequent in your area. Try sitting quietly near your bird feeder in winter where the safety and food availability encourages birds to get a bit closer for observation. If you wish to learn more about a particular species and its life history, check out ADF&G’s bird species profiles or the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s All About Birds guide.

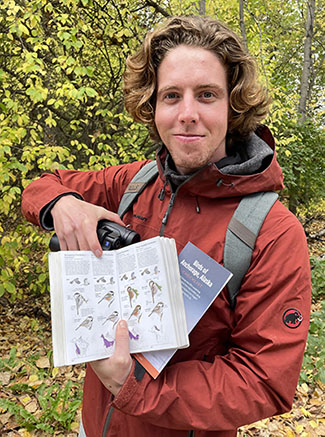

A few tools are useful, in particular, binoculars and a field guide. While binoculars are not necessary for birding, they can help a great deal with getting the best look at your subject and pinpointing identification. Even cheap binoculars are very helpful and make birding more fun. Friends may have a pair to loan, and binoculars may be available at gear rentals or through school education programs. Audubon Guide to binoculars

Bird guides, whether physical books or smartphone apps, are a great resource to take into the woods and have pictures and range maps. Range maps show where certain bird species can be found during different times of the year. If a bird you’re looking at in the book is only found in eastern Canada in the summer, then that can help rule them out as a possibility for Alaska. Pictures generally highlight key features for identification, and note similar species. Field guides focus on identification and tend to be handy, there are plenty of other great books on birds to keep at home for reading and reference.

Some recommendations for good field guides: Sibley Birds West by David Allen Sibley, Birds of North America by Kenn Kaufman. Common Marine Birds of Southeast Alaska highlights birds found in many of Alaska’s coastal areas and is free. Useful bird apps for help with ID are Audubon Bird Guide, iBird Pro, and Merlin (see table below for details).

Are you wondering where the top birding areas in Alaska are located? The “Viewing” section of the ADF&G website offers advice on where to go, what to see, checklists and other resources. George West’s “A Birder’s Guide to Alaska” is an excellent resource for planning birding adventures throughout Alaska.

Are birding hotspots accessible for you? Check out and contribute to the maps at Birdability to share information about local birdwatching spots and their accessibility, including wheelchair and bathroom access, parking fees, or accessibility by car.

If you are leaving your porch or venturing into the tundra or beach, practice safe wildlife viewing! Be mindful of bear and moose activity, bring water, watch the weather, and never closely approach or cause distress to wildlife. Also, be sure to keep your dog on a leash when walking on beaches, mudflats, or wetlands where birds can be easily disturbed. Birdwatching is about quietly and respectfully observing birds in their natural habitat without disturbance.

Keep track of your life list! You can make an Excel spreadsheet, use eBird, or simply use the printable Audubon checklists to see how many species you have identified. Many bird books can also be found for free in local libraries or requested from library databases where books are shared across the state. Create a free eBird account and use the app to also create birding checklists and keep track of your adventures and sightings as well as contribute your data to one of the biggest international citizen science databases in the world. You can also join citizen science programs like Birds ‘n’ Bogs in Southcentral Alaska, Project FeederWatch, and the Christmas Bird Count to help survey local birds throughout the state.

Alaska offers a number of birding festivals in the spring, summer and fall, and most emphasize helping beginning and intermediate birders gain skills. They also draw “power birders” and world-class bird experts with reputations for being friendly and accessible. Best of all, they are at times and in places that provide unparalleled bird viewing, in the company of local and knowledgeable guides. The Copper River Delta Shorebird Festival, the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival, the Stikine River Birding Festival, the Yakutat Tern Festival, and the Alaska Bald Eagle Festival are a few examples. An overview of Alaska bird and wildlife festivals

Birding by Sight and Sound

There are several resources and apps that can assist you in learning to identify bird species. Based on your preference you can also choose to focus on identifying birds by sound rather than sight, or vice versa. Many birders can identify birds by call or sight alone and a bit of practice and studying can lead to proficiency in either area.

| App | Details | Cost |

| Merlin | simple to bird visual and sound ID | free |

| eBird | record bird observations & join this citizen science community | free |

| Larkwire | Learn bird calls, get quizzes and tips | $4-$45 depending on size of species list. one time download |

| Sibley | App version of Sibley Bird guide, includes ID, ranges and sound. | $20 one-time download |

Sounds Wild! offers 90-second audio episodes, and many highlight birds and their songs. Topics include song birds, raptors and specifically owls, grouse and ptarmigan, woodpeckers, and a broad list of "other" birds.

How to Help your backyard birds

Once you have learned who your avian neighbors are and start recognizing the same species over and over, you will be on your way to becoming a master bird nerd! During breeding season, you may even see the same individual birds each day as they have perhaps built their nests nearby and are sharing your neighborhood. Here are a few tips to keep your local birds safe and ensure their return next year.

Try putting window clings (non-adhesive “stickers”) on your glass to reduce bird window strike fatalities and injuries. Every Alaskan has had a songbird bonk into their window and sometimes simply putting a post-it note in the glass can help the little birds recognize glass from forest reflection.

Keep your cats indoors. While many cats roam the outdoors as part of their daily routine, this can be dangerous for house cats and fatal to birds and small mammals. Outdoor cats are estimated to kill 2.6 billion birds each year in North America. Outdoor cats are much more likely to be hit by cars, attacked by other animals, or infected by diseases and parasites. Protect your cat and your local wildlife by keeping it indoors.

Coffee drinkers can also help birds. Ask your local coffee spot to provide bird friendly coffee or order online to preserve the habitat of migratory Alaskan birds in coffee farms. The Olive-sided Flycatcher is a lovely olive-gray wetland bird found throughout Alaska whose migration paths have been found to directly overlap with bird friendly coffee farms in Central and South America. The flycatcher’s population has severely declined in the last few decades and this one action could be a small step to conserving their return to our state.

Grow native plant species to promote wild bird habitat in your backyard and avoid pesticides that could harm birds. Habitat loss is the number one cause of bird decline in the U.S. and promoting the growth of native trees and flowers, and deterring invasive plants, encourages seedeaters and pollinator birds in the area. Additional trees and shrubs also provide cover and nesting habitat for breeding birds. Landscaping for wildlife

If you are an avid hunter or fisherman, consider avoiding fishing tackle and ammunition made of lead. Lead is toxic to both humans and birds, sometimes with dire consequences for already declining species. Also be sure to properly dispose of tangled fishing line and hooks. Birds such as loons can easily get tangled up in fishing gear. You can read about how difficult it is to rescue a tangled loon in the “Great Alaska Loon Rescue”.

Feeding birds in winter provides great birding opportunities. Folks living in bear country take feeders down in spring and summer, since plenty of wild food is available for birds and bears knock down feeders to eat the bird seed. Living with Birds: Guide to Building and Placing Birdhouses

The final step in this list of actions involves citizen science and bird watching! By watching birds and sharing what you see via international databases like eBird, you are contributing to our understanding of bird populations and dispersal.

The next time you go outside, see how many birds you can spot and what they look or sound like. That tiny bird with a black hat is a Black-capped Chickadee, the penguin-looking seabird a Tufted Puffin, the red-eyed waterbird with the laughing call is a Common Loon. How many species can you find?

Arin Underwood is a wildlife biologist with ADF&G’s Threatened, Endangered, and Diversity Program. She works with citizen science projects and supports research on birds and small mammals in Southcentral Alaska. Riley Woodford also contributed to this article.

Email riley.woodford@alaska.gov for a free copy of The Alaska Owlmanac, a guide to the identification, habits and habitat of ten owl species found in Alaska; and/or a print copy of Common Marine Birds of Southeast Alaska

Support fish and wildlife education and research in Alaska by purchasing a conservation stamp featuring a Bluethroat!

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.