Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

August 2022

Sunflower Sea Star

Aggressive Subtidal Predator Getting Attention

The Sunflower Sea Star is the swiftest, largest, and heaviest sea star in the North Pacific, and perhaps the entire world. That’s how Rita and Charles O’Clair described the multi-limbed predators in Southeast Alaska’s Rocky Shores in 1998, two decades before an outbreak of sea star wasting disease killed millions of sea stars on the west coast.

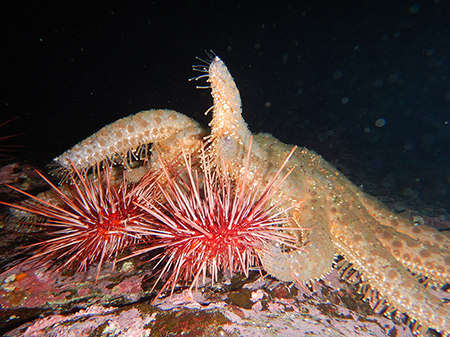

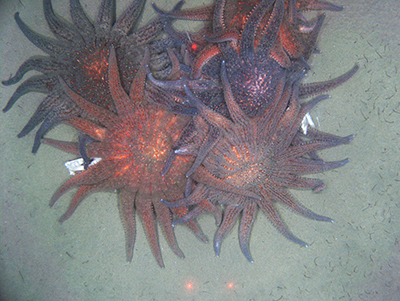

Fast-moving (for a sea star), these bottom dwelling carnivores can move five to ten feet in a minute, “outrunning” the sea urchins, snails, sea cucumbers and other sea stars they prey on. They dig clams out of the mud and sand. Sunflower Sea Stars typically have 16 to 24 limbs and can be almost a meter across.

Between 2013 and 2017, the outbreak of sea star wasting disease contributed to major declines in populations of Sunflower Sea Stars, especially across the southern portions of its range. From Baja, Mexico, north to the outer coast of Washington, the once common Sunflower Sea Star virtually disappeared. Declines in B.C. and Alaska were substantial but less severe as those further south. Although there are a number of organizations studying it, the exact cause of the disease is unknown, but there is evidence that warmer temperatures played a role.

In response to the dramatic declines, especially in the south, the Sunflower Sea Star was petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). A listing is likely to have a variety of consequences for state-managed fisheries, and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game is working to learn more about these animals and the impact listing would have on fisheries.

“If this species is ESA listed it’ll likely be throughout their range,” said Dani Evenson, a policy advisor with Fish and Game who focuses on fisheries issues. “We want to make sure we get the information we need. In the absence of information, the federal system functions on the best available science. So, for example, data from the pot fishery in Washington state might be applied up here.”

The majority of the Sunflower Sea Stars’ range is in Alaska, so understanding how the sea star is doing in Alaska is critical for understanding whether the species is truly at risk of extinction.

People don’t target Sunflower Sea Stars for harvest in Alaska, but they are caught incidentally in other fisheries. Crabbers and shrimpers pulling pots are familiar with the sight of sea stars wrapped around the bait jar.

Fisheries Biologist Andrew Olson, the groundfish and shellfish research coordinator for Southeast Alaska, recently returned from summer crab surveys for red king crab and tanner crab in northern Southeast waters. Pots are set and the catch examined and released, providing insights into crab populations, trends, movements and life history. About 30 sets are done each day, close to 200 total sets in the survey - and they are now documenting Sunflower Sea Stars as well as crab. They’ve been counting and measuring them as they come up in the pots, or stuck to the sides, he said.

Fisheries with Sunflower Sea Star bycatch could be affected by an ESA listing, because of limitations of incidental “take” of the sea stars. Under the ESA, incidental “take” means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, trap, capture or collect, or to attempt to engage in such conduct. Harm is interpreted broadly, including through a reduction in prey.

“Take is not simply killing it, even if you release a sea star from a pot unharmed, that’s still considered a take under federal law,” Evenson said. “Changing the course of its movement can count as a take, it’s not just mortality.”

“Pot fisheries are a particular concern,” she said. “If the species is listed as endangered, then the state would likely be required to get federal permits for all our research that involves pots and trawls. All Alaska pot fisheries, commercial and personal use, would likely need to operate under a new federal incidental take permit. Many Alaskans who participate in these types of fisheries could likely be affected.”

Listing Sunflower Sea Stars could also affect dive fisheries for sea urchins and sea cucumbers, sea star prey.

“It could impact the fisheries if they were found to be prey limited,” Evenson said. “It’s really the wasting disease that’s killing them; they don’t seem to be prey limited, but that’s another thing to learn more about.”

Evenson said listing killer whales in Washington impacted salmon fishing in Alaska. “An example is the Southern Resident killer whales - their diet is Chinook salmon, and so that’s affected our Southeast Alaska salmon fisheries, because salmon from as far south as Oregon swim up to the Gulf of Alaska to feed before going back south to spawn. Even though Southern Resident killer whales don’t swim in our waters, their prey does. This has added new federal rules to the fishery.”

Tracey Gotthardt coordinates Fish and Game’s Threatened, Endangered and Diversity Program. She said the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) received the petition to list the Sunflower Sea Star in August of 2021, and issued a “positive” 90-day finding in December. A positive 90-day finding does not mean that the species warrants listing under the ESA; it simply means that the petition presented substantial information, which then triggers a status review. Within 12 months of receiving the petition (by August 2022), NMFS is supposed to issue either a “not warranted” finding or a proposed listing, based on the status review. If NMFS proposes to list the Sunflower Sea Star, the notice will trigger a 60-day public comment period. The public can submit comments electronically through the Regulations.gov website.

Their Life Beneath the Waves

In conversation, biologists tend to call Sunflower Sea Stars “Pycno” or Pycnopodia, the genus name.

“They are amazing predators,” said Biologist Chris Krenz, the Wildlife Science Coordinator at Fish and Game. They are probably a keystone species, he said, an organism that helps shape an ecosystem. In fact, the concept of keystone species was inspired by studies of sea stars and their prey in the waters of Washington state in the 1960s. Their predation on mussels and urchins shapes the subtidal landscape, influencing where seaweeds and animals live and don’t live.

In more than 3,000 dives, state fisheries biologist and scientific diver Quinn Smith has seen a lot of Pycnopodia. “They’re fascinating,” he said. “They can dig pretty effectively, maybe a foot and a half into the substrate, they dig down to get clams. If you turn a digging pycno over, you often find that they are eating a big clam. Pycnos cruise around the bottom and if they get anywhere near a sea cucumber - you don’t think they could move very fast, but a Pycno shows and up they sprint away by sea cucumber standards. Same with abalone, when a Pycno gets close, it’s impressive, they move a lot faster than one would think for a snail.”

Smith is part of the Fish and Game dive team and serves as the dive fisheries research project leader. He said in the past, it was common to see Pycnopodia on dive surveys, but they didn’t collect data on them. That’s changed.

“Now, any we see on our transects, we’re counting them and measuring arm length – from center of the body to the tip of the longest arm, and noting the presence or absences of any (additional Pycno) off to the side,” he said.

Quinn said in his experience, big Pycnopodia measure 30 to 35cm from the center to the tip of the longest limb, so 60-70cm across, about 30 inches. “They’re massive,” he said, “and with 20 to 24 arms, they’re heavy. They are a big predator.”

The small Pycnopodia are in the 5-10cm range, about 2 to 4 inches across. Noting the size is important because small sea stars indicates young animals, and a lot of young sea stars could mean numbers are rebounding after the disease. Smith said when the wasting disease was moving through Southeast waters around 2017, the effect was striking.

“The whole dive team saw the wasting disease throughout the area,” he said. “Imagine a sea star melting into jelly. We’d see the wasting, and the remnants of wasted sea stars. It affected a number of species, but Pycno seemed to be the most-hard hit.”

The impact of the wasting disease was less dramatic in northern Southeast waters.

“There were very few left in southern Southeast but still quite a few in northern Southeast, in the Juneau area,” he said. “Since then, in southern Southeast, we’re seeing very small Pycnopodia. It seems like they’re starting to recover, and in the northern part they didn’t really get it or not as badly. We had the much more classical size structure – we’re still seeing a lot of very large ones and at higher densities.”

At this same time, the dive team is also seeing a large increase in numbers of sea cucumbers, which could be linked to the Pycnopodia die-off. “Pycnopodia is a sea cucumber predator, and in areas where there was a big die-off we’re seeing a big spike in the number of individuals, the highest abundance in the history of surveys in many areas.

“What’s going to be very interesting, over the next six or so years, is if we see those numbers drop back down and stabilize, as the Pycno come back,” Smith said.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.