Alaska Fish & Wildlife News

March 2022

Boreal Owls in Alaska

Takvialnguaraq

One of the Yup’ik names for the boreal owl is Takvialnguaraq. This translates to “one with poor eyesight.” This is more to do with their vision in the daytime, and not their vision at night.

The Inuit have a story about owls; it goes like this: An owl was seeking his dinner when he happened upon a napping lemming. Delighted by his luck, he wondered how to claim his prize. He dropped upon the lemming’s head and pinned him under his claws. What luck, he thought! My mate shall be so pleased, and we shall eat. But then the lemming, being clever, was playing dead. He lifted his head, startling the owl, and said: Great Ookpik! What an excellent hunter you are. You should dance so all should know, and I will sing for you. And as you dance, the lemming said, look up to the sky! And the owl looked, and danced; and the lemming escaped. When his mate arrived, she was furious. She called him a foolish mate and told him, maybe this will teach you to listen to flatterers.

Owls have an air of mystery, elusive creatures that they are. The boreal owl is no exception. Little wonder all sorts of folk tales have been built around them. They have been associated as symbols of everything from wisdom to magic to foreboding. The scientific name for boreal owls is Aegolius funereus, where Aegolius is Greek for a bird of ill omen, and funereus is Latin, referencing funereal, meaning boding ill. It’s hard to look at a boreal owl, with its moon-like face and small stature and think, “there’s an ill omen.” Maybe it’s the call, which is a fast, punctuated, phoo phoop phoop phoop that repeats about twelve times, and sounds a little like a short blow on a train whistle. Listen to owl calls here.

I’ve been lucky enough to hear them, but in spite of my efforts, have yet to spot one myself. I spoke to Dr. Doug Causey with the University of Alaska on the subject, as he had been much closer to one than I. When he first arrived in Anchorage following extended work on birds, he made it his task to see every bird in Alaska, as birders tend to do when they arrive in a new place. He was in Portage in the late fall when there was snow on the ground. And you know Alaska in the fall; the snow’s just shown itself, and the world is a little more muffled. That’s when he saw something out of the corner of his eye, just the suggestion of something that wasn’t all that it seemed to be. Lo and behold, there was a boreal owl, sitting snugly against a tree trunk. It was absolutely motionless, he told me; not moving. Now that he knew where it had made its perch, he made plans to return to the same location to observe the bird. When he did return to the tree, he did not see it again.

Nor would he; boreal owls tend not to return to the same tree. They are inclined not to move very much, but you can develop an eye for spotting them – or so I’m told. You start at the base of the tree, and slowly move your eye up, and search for any lumps that are un-tree-like. They tend to roost close to the trunk. And while I say that, they’re so perfectly camouflaged that they’re nigh-impossible to spot - best if you have some clue, like hearing a call, to guide your search. They won’t turn their heads; they’ll sit perfectly still. During the day, they sit with their eyes shut, making them all the more difficult to spot. This is to avoid competition with other predators, and even to avoid being prey themselves.

A boreal owl, Aegolius funereus, would fit into a 10” cake tin, which I wouldn’t advise if you’re trying to get any baking done. They are, appropriately, chocolate-brown with white spots. Their underparts are the reverse – white, but streaked with brown. The face is off-white, rounded, and with a defined border of tiny white and brown feathers. On the rare occasion you might see them, you can quickly identify them by their short tails, yellow bills, brilliant yellow eyes, and white eyebrow-like head-feathers.

Owls are, for the most part, nocturnal; boreal owls are really nocturnal. However, Alaska doesn’t get very dark at night in the summer – and that’s especially true further north. Boreal owls are small, efficient ambush predators; they don’t fly around to find prey, and instead sit, patient and still, until a vole or some other morsel crosses their path below. That’s when they drop, and snatch up their prey, and return to another perch to feed. Their ear holes are the most asymmetrical of any owl species, allowing them to pinpoint high-frequency sounds like a tell-tale rustle of a shrew in the undergrowth. That sound is amplified by their dish-like faces; much like radio telescopes, sound is reflected within the curve. You might see them swivel and tilt their heads as they pick up sound, and aided by their binocular vision, there isn’t much that escapes them. And like other owl species, their wing feathers are slightly rounded, with the leading edges and the trailing edges softened, allowing them to take flight and fly in absolute silence.

They capture prey under the surface of the snow by plunging straight into the snowbank – thanks to that exceptional hearing. In Alaska, the drop-and-snatch attack usually rewards the owl with a vole. In one study in Interior Alaska, red-backed voles alone made up almost half the diet (46 percent), followed by tundra voles (27 percent). A smattering of small mammals such as squirrels, jumping mice, lemmings and shrews rounded it out, with a few birds (six percent) for good measure.

ADF&G biologist Jack Whitman studied boreal owls in Interior Alaska near Fairbanks in the early 2000s; he set up close to 125 nest boxes and trapped hundreds of small rodents. This is how I have also come upon the delightful term “hooting survey.” Additional nest box studies were done as recently as 2018 by the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

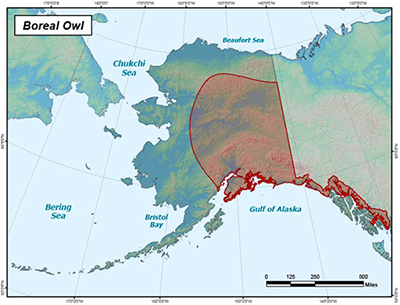

In Europe, boreal owls are known as Tengmalm’s owl. Boreal, meaning related to or located in northern regions, is an apt name. Boreal owls range in forested areas around the northern part of the Earth. They’re found in Europe and Siberia, in Alaska and across Canada, and in the Rockies and adjacent western mountains south to Colorado.

Late winter and spring is the best time to hear and maybe even see these relatively common but secretive little hunters. They sing (well, hoot) as other birds do, to attract a mate defend the area around their nests – and this is likely the best way to find a boreal owl.

More on boreal owls

Alaska’s owls and the Owlmanac

Owl research in Alaska – AFWN article from 2003

Boreal Owls Perform by Daylight – Ned Rozell

Diet and Prey Consumption of Nesting Boreal Owls in Alaska

.

Subscribe to be notified about new issues

Receive a monthly notice about new issues and articles.