Chum Salmon

(Oncorhynchus keta)

Printer Friendly

Did You Know?

Chum salmon commonly spawn in the intertidal zone at the mouths of rivers, a trait they share only with pink salmon.

General Description

Chum salmon, also known as dog salmon, are the most widely distributed of all the Pacific salmon and generally occur throughout Alaska. Like most other Pacific salmon species, chum salmon spend most of their life feeding in saltwater, then return to freshwater when mature to spawn once in the fall then die. Most chum salmon populations do not travel far upstream to spawn; however, some travel up to 2,000 miles upstream to the headwaters of the Yukon River. Although generally regarded as one of the less desirable species of salmon, in Arctic, Northwestern, and Interior Alaska, chum salmon are highly prized as a traditional source of dried winter food. Since the 1980s, commercial chum salmon harvests in Alaska have more than doubled as a result of the Alaska hatchery program and increased foreign sales.

Juveniles

During their brief freshwater residency, chum salmon fry have 8–12 vertical, uniformly-shaped and -spaced dark bars (parr marks) typically not extending below the lateral line. Overall color is dark greenish-brown along the back and pale iridescent green below the lateral line. Since they commonly migrate to sea soon after hatching, juvenile chum salmon are usually only 1–2 inches long by the time they leave freshwater.

Adults

Ocean-stage chum salmon are metallic bluish-green along the back and above the lateral line with profuse tiny speckles often present, though not resembling the larger spots of Chinook, coho, or pink salmon. The tail is highly forked, more so than other species of Pacific salmon, and is not spotted. The tail also has silver streaks along (but not between) the fin rays. As adult chum salmon enter fresh water to spawn, both sexes’ color and appearance change dramatically. Males lose their silvery appearance and take on a dark olive to brown coloration with red to purple wavy vertical stripes. They develop a hooked snout (kype) lined with large canine-like teeth. Females become brown to grey colored with a broad dark horizontal bar running along the lateral line. Females also develop kypes and canine-like teeth, though less noticeably than males.

Life History

Growth and Reproduction

Like other Pacific salmon species, chum salmon usually spawn in the fall. They can be found in two distinct races based on spawning-run timing: the earlier-running race is referred to as summer chum salmon, and the later-running race is called fall chum salmon. Small to medium, slow-flowing, spring-fed side channels are often their preferred spawning habitat, but they spawn in a wide variety of habitats including large muddy rivers, cold, clear headwater streams, and in the mouths of rivers below the high-tide line. As with other Pacific salmon, a female chum salmon excavates depressions (redds) in the gravel and deposits her eggs as one or more males simultaneously releases its sperm resulting in fertilization. The female then covers the fertilized eggs with gravel and guards the redd until she eventually becomes too weak to hold position in the stream.

Chum salmon embryos hatch from eggs after 3–4 months, depending on water temperature. Hatchlings (alevin) remain in the gravel while continuing to absorb nutrients from the egg yolk for an additional 60–90 days before emerging. They begin their migration to the sea within days or weeks.

At sea, juvenile chum salmon spend several months near shore then disperse into the open ocean. They grow rapidly in the ocean, reaching 12 or more pounds over the next 3–4 years, with the most rapid growth taking place during their final year at sea.

Feeding Ecology

Juvenile chum salmon that hatch far upriver begin feeding on insect larvae while still moving toward the sea. Upon reaching the sea, they remain near shore for up to several months feeding on crustaceans, terrestrial insects and young herring before dispersing to the open ocean. While at sea, chum salmon feed on copepods, tunicates, mollusks and a variety of fishes. When the adults return to fresh water on the spawning run, they cease feeding and their digestive tract degrades. Energy stored in body tissues (fat and muscle) is used to fuel the spawning run.

Migration

Like most Pacific salmon, chum salmon are anadromous (adults move from salt to fresh water to spawn). As adults, they almost always return from feeding areas in the ocean to spawn in the very same stream and site where they were spawned. The distance traveled to spawning sites upriver varies greatly between populations and regions, with some individuals spawning in the mouth of their home stream, and others spawning up to 2,000 miles upriver. No freshwater-resident or landlocked populations have been found.

Newly hatched chum salmon migrate, sometimes great distances, down their natal (home) rivers toward their feeding grounds in the sea.

Range and Habitat

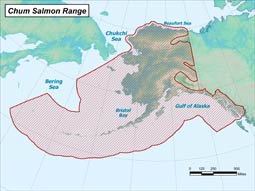

Chum salmon have the widest distribution of any of the Pacific salmon. They range throughout Alaska, but are scarce north of Kotzebue Sound. Elsewhere they are found along the east and west coasts of the North Pacific Ocean north of northern California (Sacramento River) and Kyushu, Japan, and along the Arctic Ocean coast east to the Mackenzie and Anderson rivers in Canada and west to the Lena River in Russia. While at sea, most of Alaska’s chum salmon remain in the eastern Chukchi and Bering seas and the Gulf of Alaska.

Chum salmon usually spawn at the mouth, or in the lower sections, of rivers, although in Alaska’s largest river systems, some travel great distances (up to 2,000 miles to the upper Yukon River in Canada) upriver to spawn. After hatching, juvenile chum salmon spend a short time (days to weeks) in fresh water before migrating to the ocean. Once in the ocean, juvenile chum salmon remain near shore, particularly in shallow eelgrass beds, for the first several months before dispersing into the open ocean.

Status, Trends, and Threats

Although Pacific salmon species on the West Coast of the Lower-48 States have experienced dramatic declines in abundance during the past several decades, salmon populations in Alaska are generally faring better. Freshwater habitat in Alaska remains mostly pristine. There are hundreds of stocks of chum salmon throughout the state of Alaska and their population trends are diverse: Some stocks are in decline while others are at equilibrium or increasing. Chum salmon stocks from some Western Alaska rivers are at very low levels; however, causes for this decline are largely unknown. In Southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound, wild chum salmon populations and harvests steadily declined through the early 1900’s and hit an all-time low in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Following the start of Alaska’s hatchery program in 1971, the numbers of chum salmon returning to Southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound have returned to high levels. Now hatchery fish make up more than half of the total commercial chum salmon harvest in Southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound. In Southeast Alaska, wild chum salmon production has also increased during the growth of hatchery production and is generally stable. Potential future threats to chum salmon in Alaska include habitat loss, climate change, over fishing, and competition from hatchery fish.

Fast Facts

-

Size

Average 24-28 inches and 10-13lb; males usually larger than females -

Range/Distribution

Chum salmon range throughout Alaska, but are scarce north of Kotzebue Sound. While at sea, most of Alaska’s chum salmon remain in the eastern Chukchi and Bering seas and the Gulf of Alaska. -

Diet

Insect larvae, copepods, tunicates, mollusks and a variety of fishes -

Predators

Marine mammals, birds, bears, wolves, humans -

Reproduction

Spawn only once before dying -

Other Names

dog salmon, calico salmon

Did You Know?

- Chum salmon are the second largest of all the Pacific salmon, second only to Chinook salmon.

- Chum salmon commonly spawn in the intertidal zone at the mouths of rivers, a trait they share only with pink salmon.

- In the Yukon River system, chum salmon migrate upriver as far as 2,000 miles to spawn in interior Canada.

- Chum salmon can be found along the Arctic coast of Alaska, Canada, and Russia.

- Chum salmon fry spend only days or weeks in freshwater before moving downstream to saltwater.

- Chum salmon can be found in two distinct races based on spawning-run timing: the earlier-running race is referred to as summer chum salmon, and the later-running race is called fall chum salmon.

- In saltwater, several species of Pacific salmon look very similar. However, unlike Chinook, coho, and pink salmon and steelhead, chum salmon have no dark spots on their back or tail. And unlike sockeye salmon, chum salmon have silver streaks along the rays of their tail fin.

- Chum salmon typically mature at 3, 4, or 5 years of age.

- Spawning male chum salmon have large canine-like teeth, which they use in attacking other males on the spawning grounds.

- Fossils demonstrate that Pacific salmon have existed for at least 6 million years.

Uses

In Arctic, Western, and Interior Alaska, where they are highly sought after as a traditional dried winter food supply for humans and dogs, chum salmon are harvested in greater numbers than any other salmon species. Though the least valuable (per pound) of all Pacific salmon species, chum salmon have ranked second (to pink salmon) in average annual catch in Alaska’s commercial salmon fishery since statehood. Chum salmon are typically marketed as a canned or smoked product and exported to Asia and Europe. Chum salmon flesh is lighter in color and oil content than other species of salmon, but its firmness and flavor, if caught fresh, make chum salmon a pleasant substitution for other salmon species.

In the sport fishery, anglers generally prefer chum salmon less than other salmon species, as they have typically begun deteriorating by the time they reach popular sport-fishing areas. Where they spawn near the coast, chum salmon have a tendency to begin to “turn” prior to leaving the sea. However, when targeted near river mouths prior to, or soon after, entrance into freshwater, chum salmon can provide excellent action on sport fishing gear.

Management

The Alaska State Constitution establishes, as state policy, the development and use of replenishable resources, in accordance with the principle of sustained yield, for the maximum benefit of the people of the state. In order to implement this policy for the fisheries resources of the state, the Alaska Legislature created the Alaska Board of Fisheries (BOF) and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G).

The BOF was given the responsibility to establish regulations guiding the conservation and development of the state’s fisheries resources, including the distribution of benefits among subsistence, commercial, recreational, and personal uses. The ADF&G was given the responsibility to implement the BOF’s regulations and management plans through the scientific management of the state’s fisheries resources. Scientific and technical advice is also provided by the ADF&G to the BOF during its rule-making process. The separation of rule-making and inseason management responsibilities between these two entities is generally regarded as contributing to the success of Alaska’s fisheries management system.

The ADF&G’s fishery management activities fall into two categories: inseason management and applied science. For inseason management, the department deploys a cadre of fishery managers near the fisheries. These individuals have broad authority to open and close fisheries based on their professional judgment, the most current biological data from field projects, and fishery performance.

For access to chum salmon research reports, visit our e-library.

Research

Research biologists and other specialists conduct applied research in close cooperation with fishery managers. The purpose of ADF&G’s research is to ensure that the management of Alaska’s fisheries is conducted in accordance with the sustained yield principle and that managers have the technical support they need to ensure that fisheries are managed according to sound scientific principles and utilizing the best available biological data.

A variety of research projects on chum salmon stock assessment, harvest levels, population dynamics, genetic stock identification, occurrence and distribution, and habitat quality are conducted each year statewide. Such projects are often conducted in collaboration with universities, and federal and international institutions. The results of these works are peer-reviewed and presented as written articles as well as presented at scientific conferences and meetings throughout the world.

For access to chum salmon research reports, visit our e-library.

Get Involved

More Resources

Fishing

- Commercial Fishing

- Sport Fishing

- Subsistence Fishing

- Personal Use Fishing

- Angler Education

- Salmon Enhancement and Hatcheries

- Salmon Forecasting in Alaska: Who Needs to Know?

- Fish Counts